In Abbas Kiarostami’s Close-Up, art imitates life. Or perhaps the other way around. Frankly, it’s kind of hard to tell, though the film very handily proves beyond a shadow of a doubt the hoary old adage that truth is indeed stranger than fiction. For many, Kiarostami may best be known as the wacky Iranian filmmaker behind Taste of Cherry, that bleak, minimalist, comprehension defying arthouse staple of college communication courses all over the world; he’s also one of the most well-tenured directors still working today who deserves the title of “master”. Kiarostami has been making movies for over forty years, and at the ripe old age of 73, he still feels shockingly vital.

Close-Up, arguably, remains his most important movie even today in 2014. No, it’s not the project that won him the Palme d’Or – that would be the aforementioned Taste of Cherry – but erase it from his oeuvre and his career becomes altered in unknowable ways. Taste of Cherry solidified Kiarostami’s position as one of world cinema’s most important directors; Close-Up, on the other hand, laid out the foundation for his ascent to international recognition. It’s also uncompromisingly heady, a faux documentary that willfully blurs the meaning of the distinction and winds up defying easy categorization in the process. (F For Fake may well be the only other doc in the Criterion library that matches Close-Up for sheer intellectual rigor.)

And it all comes down to a simple matter of identity theft, spurred on by a love of cinema and a desire for a better life (or the illusion of one). Nobody, not even Kiarostami, could come up with a basic conceit this weird on their own. On that same token, perhaps only Kiarostami would make a film about Close-Up‘s central crime from such a metatextual angle as he does. He does not simply chronicle the courtroom drama that unfolds in the wake of the aforementioned transgression, though he does do that; he also invites all involved parties to participate in reenactment, asking them to walk through the same steps that brought them all to trial together to begin with.

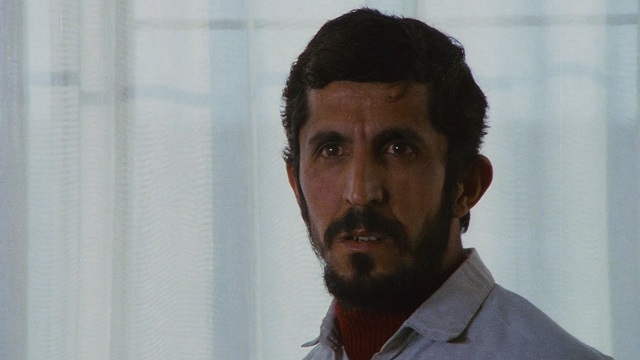

Close-Up finds its origins in a bit of chicanery that took place in Tehran in the late 80’s, when a poor man named Hossain Sabzian successfully impersonated the Iranian filmmaker Mohsen Makhmalbaf to a middle class family. Sabzian perpetrates his ruse seemingly on a whim, or at least that’s the sense we get from decoding the first recreation of the film; it’s a chance encounter on a bus, where Sabzian charms his way through the incredulity of Mahrokh Ahankhah, the family matriarch, and convinces her of his trustworthiness. The Ahankhahs believe in Sabzian’s cover for a time, though eventually his lies fail him, reality catches up to him, and he’s found out, arrested, and put on the stand to explain himself before the gathered members of the local judiciary, as well as the Ahankhahs, in court.

Odd, no? Close-Up feels like the stuff of fiction, and yet, against all reason, it actually happened. Couple the uniqueness of the case with its inherent ties to the film world, it is, perhaps, unsurprising that Kiarostami elected to commit the Sabzian/Ahankhah saga to the screen; people are fascinated by celebrity and fame, no matter where they live and no matter what era. Last year’s The Bling Ring repurposed a similar (if less outlandish) incident for the sake of narrative art, but Sofia Coppola hired actors for her main cast and only featured cameos by the victims of the breaking and entering spree that provided the focal point of her film. Kiarostami’s tact with Close-Up feels infinitely less safe, not only for Sabzian and for the Ahahnkhas but for himself as well.

And that daring-do alone makes Close-Up worth a look, if not two. Kiarostami takes on the role of ringleader here, staging sequences of reenactment from behind the obstructive wall of his camera, but he also takes an active part in the film as Sabzian sits in judgment before the law; quietly, without allowing a single note in his voice to betray sentiment or even perspective, Kiarostami peppers Sabzian with questions about his intentions. Kiarostami wants the truth, but he’s also rather shamelessly indulging his own personal curiosity: why does Sabzian pass himself off as Makhmalbaf? Does Sabzian want to be a director? When it’s revealed that Sabzian actually thinks he would be a better actor, Kiarostami wonders aloud why the man didn’t just claim that he’s an actor to begin with?

The answer to this last query is so shockingly obvious that to hear Sabzian’s reply is to feel utterly foolish: by identifying himself as Makhmalbaf, Sabzian was merely playing a part, though the eldest son of the Ahankhah clan offers the theory that Sabzian is playing a part through his expressions of remorse and humility. Perhaps the efficacy with which he dupes the Ahankhahs alone suggests that he has a bright future as a thespian ahead of him, once he accepts the punishment handed down to him by the court. Mercy is a huge element in Close-Up. Is Sabzian’s crime truly all that heinous? He siphons money off of the Ahankhahs, but pleads in earnest that he did not lie about his identity to steal from his benefactors. His trickery isn’t inspired by malevolence, but desperation.

In the end, though, Kiarostami isn’t truly interested in Sabzian’s guilt, at least not in more than a tangential sense. Instead, he’s compelled more by the power cinema has to beguile and deceive us. As Sabzian misleads the Ahankhahs, so too does Close-Up mislead Kiarostami’s audience. The film commences its mind game with us from the very first scene, in which the investigative journalist responsible for breaking the case grabs a cab on his way over to the Ahankhahs residence. What, exactly, are we watching? How much do these reenactment scenes reflect the genuine ebb and flow of the events that inspired Kiarostami to make this film in the first place? How much are these performances influenced by emotions swirling outside of their context? There’s so much sleight of hand perpetrated here that it’s impossible to track the film’s verisimilitude: Kiarostami persuaded the judge to come to his verdict, while the ending sequence in which Sabzian meets and goes on a motorcycle ride with the real Makhmalbaf is an invention for the film. (The Ahankhahs actually wanted Sabzian to be imprisoned for his transgressions. Understandably, the conclusion here infuriated them.)

Maybe Kiarostami doesn’t really care about ruffling feathers in pursuit of his greater artistic goals. Scratch that: he most assuredly does not care, and seems far more interested in how cinema as a medium motivates and defines Sabzian as a human being, while also shaping his very existence. Justice is a tertiary concern here, while Kiarostami’s examination of both his chosen medium and Sabzian’s persona take precedent. Close-Up isn’t the first or last time the filmmaker plays with his viewers’ perception – see 2011’s Certified Copy – but it does mark his arrival as an auteur of misdirection, and an artist with a deep-rooted interest in humanist narratives.

2 thoughts on “The Second Criterion: “Close-Up””

I saw Close-Up for the first time about a year ago. I’m still trying to wrap my head around it.

More or less my experience, too. The first viewing wrinkled my brain. The second ironed it out. This isn’t light viewing, but man is it ever rewarding.

Probably remains my favorite Kiarostami film.