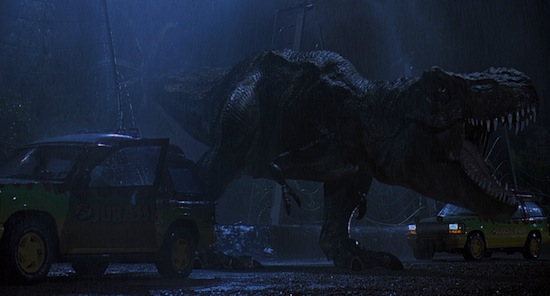

The theatrical experience is one-of-a-kind. Try as hard as you can to recreate that experience at home with a big screen and a Blu-Ray player, but it just isn’t the same. That’s why theatrical re-releases are so wonderful. They offer an opportunity to see a film on the big screen again, sometimes for the first time. Take, for example, Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park, which is back on the big screen today. It’s one of my favorite films of all time, but I’ve only ever seen it on various home video formats. The chance to see those dinosaurs on a huge screen with huge sound is incredibly enticing, but there’s just one problem: the film has been converted to 3D.

Converting catalog titles to 3D has been around for a few years now. The trend began in 2006, when Disney re-released The Nightmare Before Christmas in post-converted 3D to great success. Since then there have been numerous re-releases of older films in 3D, including Toy Story, Toy Story 2, The Lion King, Beauty and the Beast, Star Wars: Episode I, Titanic, Finding Nemo, Top Gun and Monsters Inc. This year is also set to see 3D re-releases of Independence Day and The Wizard of Oz.

There are all sorts of reasons to find this trend annoying. A lot of people don’t like 3D, which is a problem. On top of that is the question about whether conversion to 3D is a change to the work of art akin to colorization. Then there’s the simple fact that many people want to watch these films on the big screen purely to re-experience the film as it was originally shown. Of course, maybe the most annoying thing of all is that 3D conversion of classic titles and the premium ticket price accompanying them feels like a huge cash-grab on the part of the studios.

There’s no question that these re-releases are a cynical ploy to make money. It is the movie “business,” after all. But I don’t think it’s entirely as simple as a studio seeing easy money in slapping 3D on a classic and charging $3 more per ticket. The fact is, these re-releases cost a lot of money. The 3D conversion itself can cost upwards of $10 million or even $20 million. Then there’s the significant cost of publicizing and distributing a wide release. And all this money for films that people presumably have already paid to see and are generally widely available on home video. Even if you take away the cost of 3D conversion, the cost to do a wide re-release of a film may be too high a risk for a studio.

That’s where the 3D comes in, though. First of all 3D, for whatever reason, is a really big deal overseas. The Titanic re-release last year saw domestic returns of about $57 million, which would stand as a pretty decent number for a re-release, except that it took in a staggering $285 million overseas. International audiences love Titanic and they love 3D movies. So that alone makes the 3D conversion worth it, but there is another reason to convert classics to 3D that’s a little less obvious: marketing.

Even in North America, where 3D has been less successful—2D screenings of 3D movies often sell higher volumes of tickets—and where people are far more skeptical of 3D, the use of 3D as a marketing tool in these re-releases is indispensable. If you’re trying to get hundreds of thousands of people, or even millions, to come see a movie they’ve already seen many times before, you need to offer something new. Seeing the film on the big screen again might attract a lot of people, but it’s not enough of a marketing hook.

Before the home video era, theatrical re-releases were quite common. But of course they were common. The only way people could watch many of these films, unless they were shown on broadcast television, was to go to a movie theatre. VHS killed that. Theatrical re-releases simply weren’t necessary anymore. So what did we start seeing in the ‘80s? The “Special Edition.” Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Blade Runner, Star Wars, E.T., Alien. All these films saw big theatrical re-releases, but all of them used the gimmick of new scenes or new special effects as a marketing hook to bring audiences back.

Disney continued re-releasing their animated films unchanged for a number of years, but even they had a gimmick: the Disney Vault. Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was the last standard Disney re-release, coming back to theatres in 1993, which still pre-dated the film’s first ever home video release on VHS in 1994. The next re-releases, in the early ‘00s, were Beauty and the Beast and The Lion King. Both “Special Editions” with added scenes, and both released exclusively in IMAX and large-format theatres.

The fact is marketing requires a hook. If you’re selling something you need an element that will, if not outright attract people, at least get them to take notice. Put out a trailer for a new theatrical release of Jurassic Park and people might just brush it off. Sell it as “for the first time in 3D!” and now people will pay attention. In fact, even people who despise 3D will likely take more notice, and then there’s the hope that, like me, they’ll put aside their issues with 3D and post-conversion just to see the film on the big screen once more.

Sure, it’s all very cynical and it’s all about making money, but that’s the nature of Hollywood. It makes sense that in the era of home video studios would need a good marketing hook to attract audiences for a big screen re-release, and that’s how it’s playing out. 3D is just the latest way to grab attention and hook people in. In some ways it’s actually better than the previous method of adding new scenes and CG effects. It might suck having to watch Jurassic Park through 3D glasses, but at least the guns haven’t been changed to walkie-talkies and Hammond isn’t stepping on the T-Rex’s tail.

3 thoughts on “The Real Reason Behind the 3D Re-Release Trend”

I can’t speak to your local theaters, but several of the larger multiplexes in my area have a limited number of 2D Jurassic Park showings this weekend as well as the 3D and IMAX 3D ones.

Pingback: The Return of Classics from Film Lost-and-Found | Lone Star Film Society

Pingback: The Return of Classics from Cinema's Lost-and-Found | Lone Star Film Society