If Fugazi were the defining post-hardcore band, collecting the shards of numerous dead-end underground sub-movements back into a unified contradiction of melody and abrasion, then Jem Cohen’s Instrument is the defining post-hardcore film. Visible film strips and markers break up the collection of live and archival footage, while sudden fluctuations in speed give the documentary the feel of everything from a relatively slick music video to a silent picture. Indeed, the entire opening segment of the film is filtered through an amber lens and broken up by black screens with lyrics printed in white lettering that resemble intertitles.

Cohen favors observation so direct it borders on the abstract, and though the footage Cohen shot for Instrument largely consists of straightforward footage of the band rehearsing and gigging, the sheer glut of material amassed in the 10-year span of filming necessitates an freeform editing scheme that trades any sense of narrative structure for the alternating rush and tedium of being a rock band. Exhausting concerts alternate with exhausted traveling and restful retreats, and occasionally those moods overlap, placing sedate, drained speech from the band members or idle practice over images of the group bouncing around on stage, dancing with each other and dropping to the ground in punkish approximations of James Brown showstoppers.

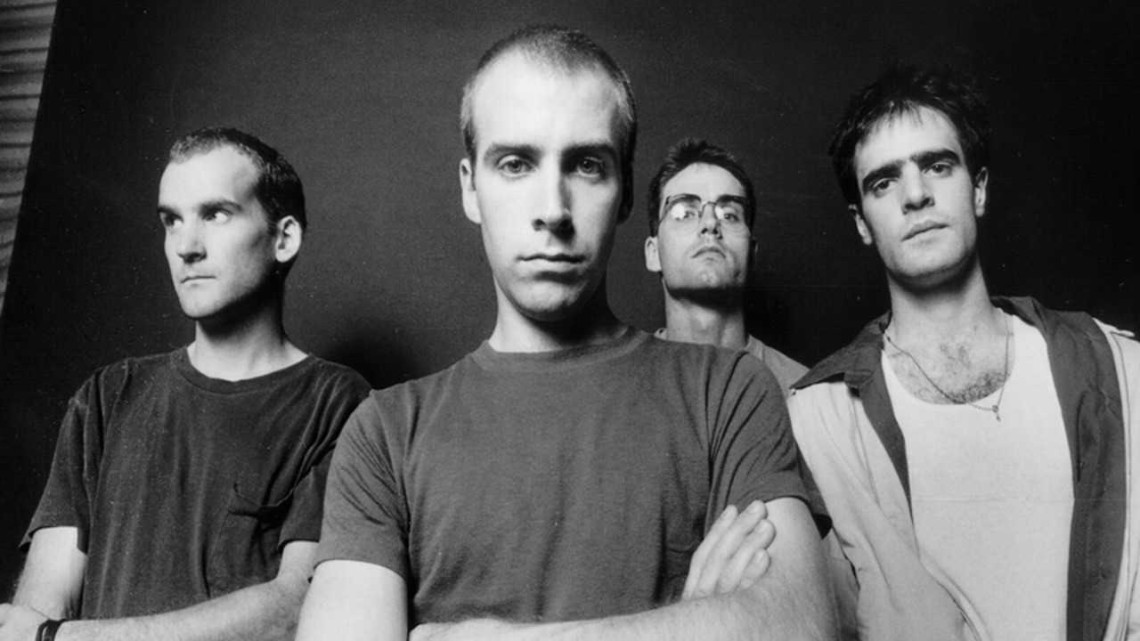

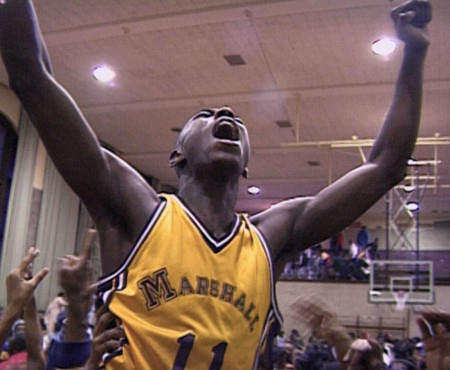

The most rewarding, and revealing, of Cohen’s editing feats is the regular intermingling of material from gigs played years apart. Even an inattentive viewer can spot the difference between a later show played for 1,000+ pogo-ing kids long hip to the word of mouth and a foundational gig played at local D.C. benefits, and it’s fascinating to see the band build its reputation through its committing touring. The early shows are incendiary, displaying a band with a controlled sense of abandon, epitomized by Guy Picciotto’s dancing style of throwing and catching himself and twisting himself into wild contortions. (In one performance, played in a high school gym, Picciotto even worms his way through a basketball hoop, to the bewilderment and delight of a small but thrilled audience.) Yet if the later shows lack some of the euphoria of the early gigs, it’s not because the band is any less exciting or raw. They’ve merely built their audience to the point that there’s no longer enough room for everyone to dance around with the group.

Cohen largely avoids direct interviews, and even when he addresses the band members during down time, he tends to focus on the more mundane matters of whatever Fugazi is doing at that moment. When it comes to the band’s forthright politics and ethos, Cohen prefers to approach the subjects obliquely, placing disembodied snatches of Ian MacKaye talking about his vision for music over pillow-shot transitional images, or simply using tapes of interviews conducted by journalists to stand in for a direct conversation between filmmaker and artist. Even those interviews do not always lay out the group’s views, as Fugazi would rather be political through their musical aesthetic and business practices than through pontification. MacKaye and Picciotto state this point to an 8th-grade student who interviews them for public-access TV, but the fact that they are freely, respectfully talking to her for a free local channel exhibits that ethos while they talk about it. Some of the most compelling scenes in the film show the band playing with all their passion for local charities and, in one instance, for the prisoners of D.C.’s Lorton Correctional Facility, who dance, hug, and even come up on stage to play around on the drums as a officials look on with bemusement. Fugazi’s lifespan ran parallel to the explosion and equally rapid implosion of the underground into the ‘90s alternative mainstream, but such footage shows a band situated wholly outside trends and commercialization, and above all one leaves this film with the impression that Fugazi may be the only band in history to never sell out.

Shot from the first 1987 shows through the tour for End Hits, Instrument very nearly presents the entire Fugazi experience, stopping just a few years short of the band breaking up in everything but name in 2002. Filled with longueurs and occasionally frustrating in its tendency to cut away from the band’s killer live shows just as momentum builds, the film nonetheless uses these disruptions to capture the band’s life as it was, a blur of strident opinions, careful song-making, and blistering sets, all of which combined to sell the group to listeners in lieu of record company hype or MTV acceptance. Looking back from a time in which the music industry as a whole has collapsed to the point that hardly anyone holds it against an indie act for licensing a song to sell cars, the band’s furious integrity is almost quaint, an unintentionally revealing glimpse at how much better things were even for the outcasts in the days before the Web. But in the splinters of punk, dub reggae, noise rock, and plaintive singer-songwriter styles that criss-cross over the film’s broken musical portrait, Fugazi’s ethical commitments matter far less than a simpler truth: they may be the best damn rock band this country ever produced.

If you’re interesting in watching Instrument on Fandor, use your Movie Mezzanine coupon for an exclusive discount and access to a breathtaking library of cinema!

One thought on “Spotlight on Fandor: “Instrument””

Fugazi. Probably one of the greatest bands ever that the public isn’t aware of. Guys who were completely independent to the core. Not doing interviews with magazine that sells tobacco and alcohol. Maintaining the idea that fans can pay $5 for a show. That is true punk rock.