Wittgenstein introduces the Austrian-British philosopher as a boy (Clancy Chassay) sitting at a table, jotting down a note. “If people did not sometimes do silly things,” the lad says haltingly as he scribbles along, “nothing intelligent would ever get done.” Having worked out the idea, the child then turns to the camera and confidently repeats it, no longer feeling out the sentence’s contours but presenting it as a gem of completed thought. Little Ludwig then introduces himself as a prodigy, speaking with the confidence of a child inculcated in a home of wealth, art, and intellectual connections.

But as Derek Jarman’s 1993 black-box biopic follows the boy through his education to his emergence as one of the world’s leading thinkers, the film replaces this cocky image of a wunderkind with that of a repressed adult riddled with self-doubt. The pep in Chassay’s voice becomes the rushed insecurity in Karl Johnson’s tone as the adult Wittgenstein parlays his younger self’s hatred of formal education into a worldview that rejects the preexisting tenets of philosophical theory. Where philosophy typically concerns the Self as the focal point of existence and understanding, Wittgenstein imagines an inverted scheme in which class, religion, culture, geography, and other social factors (including the fresh wounds of World War I) define the parameters of one’s self-perception.

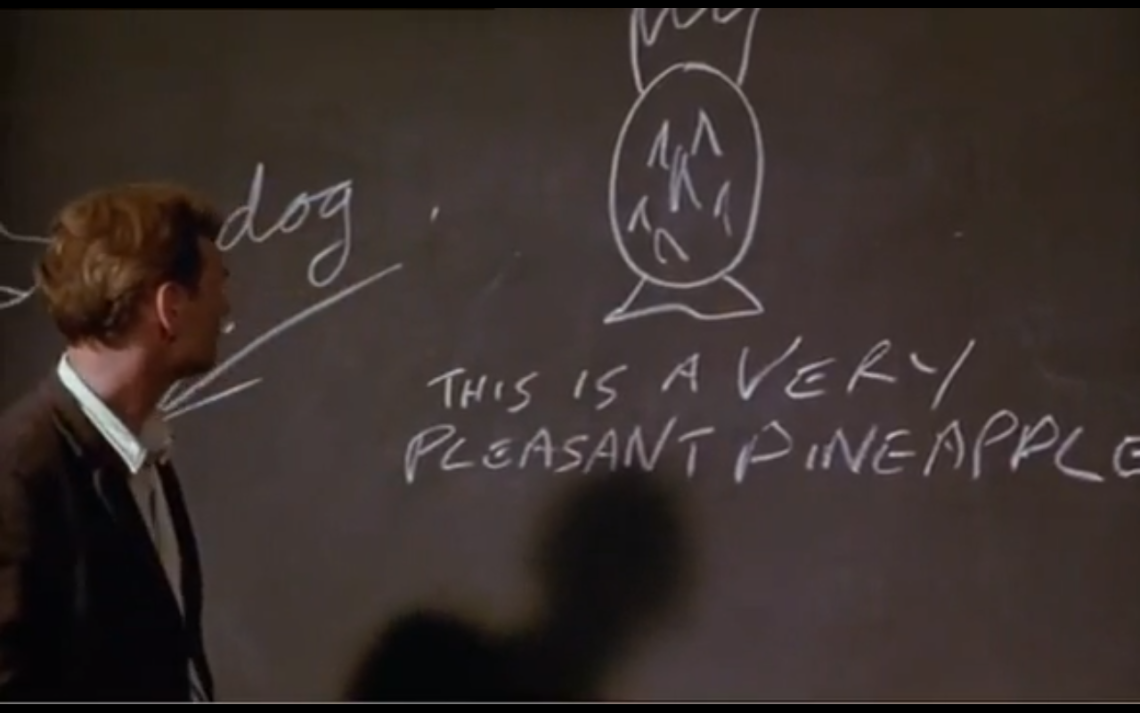

Jarman plays out the reaction to this theory among other students and philosophers as a comedy of manners, pitting the frantic stammers and belligerent temper of the boy wonder against the scoffs of peers and the confused, mildly worried looks of students gradually realizing that their professor is a madman. The director portrays the insular world of academia as a pit of pharisees and close-mindedness, even in an early scene of young Ludwig being instructed by private teachers arranged as if on a tribunal, looming around him in a crescent and simultaneously gibbering lessons from ancient, obsolete books to the point that their voices converge into one unintelligible squawk not unlike the teacher from Peanuts. Dialogue is also frequently hilarious: When Bertrand Russell (Michael Gough) haughtily responds to Wittgenstein’s desire to leave philosophy with “So what are you planning to do for the rest of your life?” Ludwig responds, “Well, I shall start by committing suicide.”

In another film, Wittgenstein’s dramatic break from established theoretical norms might have also served as a metaphor for the philosopher’s homosexuality, hinting at that aspect of his psychology while pointedly keeping focus on anything else. Instead, Jarman, as was his more-confrontational wont throughout his career, encodes queerness into his film’s DNA. Tilda Swinton plays the patron Lady Morrell less as a human being than the embodiment of her billowing, chromatic wardrobe. She’s forever lounging around as if posing for a portrait without an artist, letting venom pool in the back of her throat before laconically spitting it at targets. Gough gives one of his best performances as an especially bitchy Russell, lending Socratic dialogue a cattiness it sorely lacked. Rather than portray Wittgenstein as the victim of a cruel, straight society, Jarman ironically turns the man’s philosophy on him, surrounding the man with a queer context that the supposedly far-seeing thinker could not see right in front of him.

This inability to recognize the world that Wittgenstein believes gives him definition is also reflected in the production design. Jarman shoots the film against black curtains that seal off the world, populating a void only with a handful of actors and minimal, if vibrantly colorful, props. Ludwig spends much of the film railing against academia and encouraging people to drop out to take up more useful physical labor in order to get a truer sense of the world. But the hermetic vision of the film gives away his privilege, restricting the perimeter of Wittgenstein’s world to the classrooms and egotistical exiles that fill his life. Only at the end, when the man lies on his deathbed, is the curtain pulled back to reveal a purplish sky poised either at sunrise or sunset, the ambiguity of its timing at once the final joke on the logical traps of Wittgenstein’s theories and a release from their most dogmatic elements.

If you’re interesting in watching Wittgenstein on Fandor use your Movie Mezzanine coupon for an exclusive discount and access to a breathtaking library of cinema!