Editor’s note: We are thrilled to announce that MUBI, the curated online cinema that brings its members a hand-picked selection of the best independent, international, and classic films, is sponsoring Movie Mezzanine. You can use the discount on this promo page to check out all of MUBI’s selections.

Even the most serious-minded of Agnès Varda’s documentaries have an impish playfulness to them, with her sing-song narration and idiosyncratic structures revealing a relaxed inquisitiveness. Her cinephilic nonfiction regularly includes cats as a tribute to her departed friend Chris Marker, but her own curiosity for all things could make the animals a fitting avatar for her as well. Perhaps the most famous of Varda’s documentaries is The Gleaners & I, a study of individual and collective efforts to tackle both hunger and excess food waste in France.

The paradox of food scarcity and rampant waste in the West has spawned numerous nonfiction films in recent years, most of them tedious lectures filled with scare tactics and finger-pointing. Varda’s film is the antithesis of such message movies; its focus is intimate, suggesting political implications at the fringes, and its tone is one of good humor and warm delight at the ingenuity of people. “Gleaners” refer to people who cull the remnants of fields after harvest, collecting undesirable or otherwise unpicked fruits and vegetables. Varda is quick to point out the historical precedent for this action, and her chipper narration even betrays a certain pride that the practice was codified and legal in France as far back as the Renaissance.

The film is at its most polemical when it reveals that rights afforded even to peasants have now been rescinded, with the modern equivalent of urban gleaning—dumpster diving through markets’ mass disposal of perfectly good but unsold food—has now been banned by private interests. But instead of tackling this head-on to question the absurdity of supermarkets refusing to let food they’ve already discarded by taken by others, Varda finds people who do it anyways, and the mixture of political stridency and simple need offered by the contemporary gleaners as excuses comes to set the film’s tone. Varda views the practice as part of a sociological ecosystem, one in which a network of gleaners either get around padlocked dumpsters and other hindrances or receive knowing aid by sympathetic proprietors, including a restaurateur who can trace his family back to gleaners and who sees his function in offloading material he cannot use anyway as part of the social contract. The breadth of the movie’s social outlook slowly coalesces around such figures, taking a fundamental human need and building from it a vision of a collaborative (and competitive) society in microcosm.

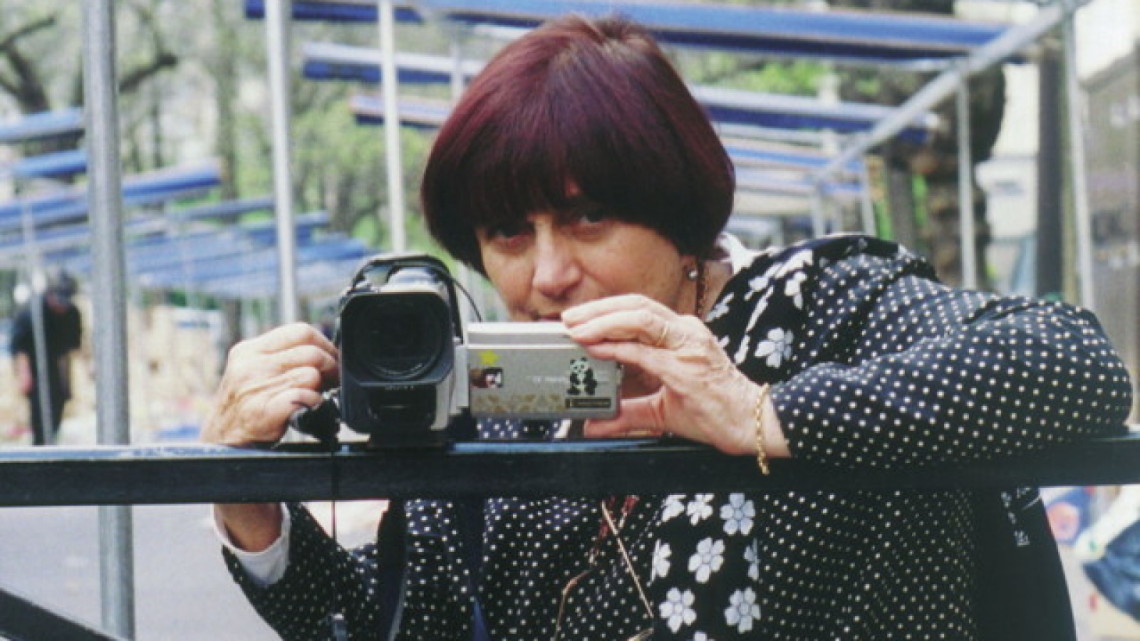

Eventually, this vision broadens even further, riffing on the notion of gleaning to apply it to concepts of art. Varda inserts numerous digressive shots of various objects found scattered among junk shops and food bins, and the camera regards them as if it were Varda’s own eyes, inspecting each thing to weigh its possibilities. She also interviews artists who use recycled objects and probes the mentalities behind crafting new works from the old. Naturally, Varda implicates filmmaking into this, thinking of herself as a “gleaner of images” for regularly putting into films the sort of things that other filmmakers omit. (That Varda is known for making films about and starring women adds a poisonous edge to this comment that the director is content to let others suss out for themselves.)

Occasionally, Varda foregrounds herself to the detriment of the picture—one interview subject, in a follow-up interview, even criticizes her for making parts of the movie about herself—but her freeform approach to a loaded subject, turning a call to action into an extended exquisite corpse game that considers all the way humans naturally make treasure from another man’s trash. It’s the kind of twist that Varda excels at, not a narrative sucker punch but a tonal complication. Ironically, all the diversions make a better bid for gleaning in the modern age than most documentaries that make this demand their raison d’être, as the film calmly suggests that gleaning is the default state of human life, which makes any attempt to impede it an unnatural disruption.

If you’re interesting in watching The Gleaners & I on MUBI, use your Movie Mezzanine coupon for an exclusive discount and access to a breathtaking library of cinema!