“Everything sunny all the time always!” assures Kim Jong-Il (comedian Margaret Cho in dictatorial drag) during a North Korean weather report on an episode of NBC’s “30 Rock,” in which a prominent media personality is kidnapped by the Communist nation and put to work as a spokesperson for pro-government propaganda. It’s a funny yet vaguely disturbing storyline, playing on the popular image of Kim as a media-obsessed leader with a deranged personality.

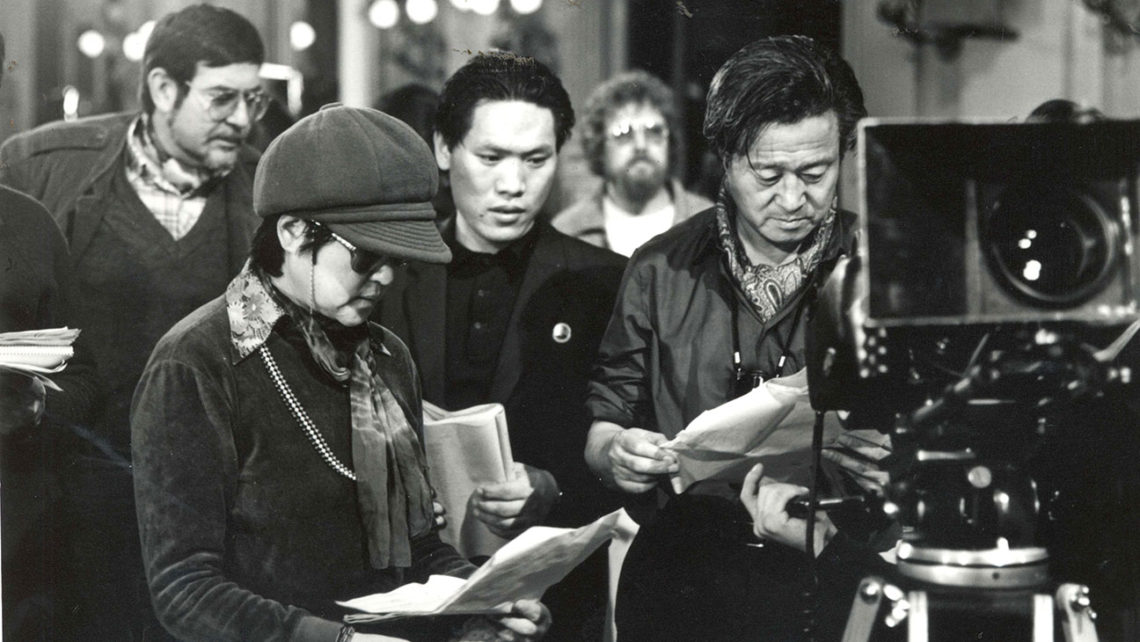

It turns out that this conceit was not so far from the truth. Ross Adam and Robert Cannan’s The Lovers and the Despot documents a harrowing and oddball slice of history, during which South Korean director Shin Sang-ok and his estranged actress wife Choi Eun-hie were kidnapped in 1978 and forcibly put to work by Kim as his personal propaganda filmmaking team, producing over 17 films until their dramatic escape to the United States in 1986. Equal parts espionage thriller and star-crossed romance, Adam and Cannan’s film covers the couple’s relationship from the early years of their marriage, their falling-out after Shin’s affair with another woman, and their fateful reunion as ostensible prisoners of the North Korean government.

For such a compelling true story, Adam and Cannan’s approach to the material is rather unremarkable. The usual visual tenets of crime procedural documentary are accounted for. There’s the handful of taped conversations between Kim, Shin, and Choi played over the image and analogue hiss of a spinning cassette deck. There are dramatic close-ups of police reports, highlighting relevant passages and words. And then there’s the Errol Morris-esque dramatic recreations of Shin and Choi’s kidnapping. (Though, unlike Morris’ use of them in The Thin Blue Line, these recreations are not so much revelatory as they are simply illustrative. Yawn.) It’s a straightforward retelling augmented by archival footage of Shin (who passed away in 2006) interviews with Choi, her children (who were basically orphaned for the duration of the kidnapping), and those involved in the missing-persons investigation and eventual rescue.

For decades after their political asylum in the United States, Shin’s motives were called into question. Was he secretly a North Korean agent? Was Choi merely a pawn in his plot? The film errs on the side of Shin’s innocence and where it succeeds the most are in Choi’s interview segments. She evocatively describes her experience, like her chilling first meeting with Kim, which involved a private screening of the 1956 Soviet film The Forty-First, the tragic ending of which she read as a warning against betraying the Communist state under penalty of death. “There’s acting for films and there’s acting for life,” she explains of her and Shin’s acquiescence to Kim’s demands to improve the international regard for the North Korean film industry, and under any means necessary show that “everything sunny all the time always.” The Lovers and the Despot is not a ground-breaking piece of filmmaking by any metric, but will likely satisfy those with a curiosity for off-the-beaten-path film history.