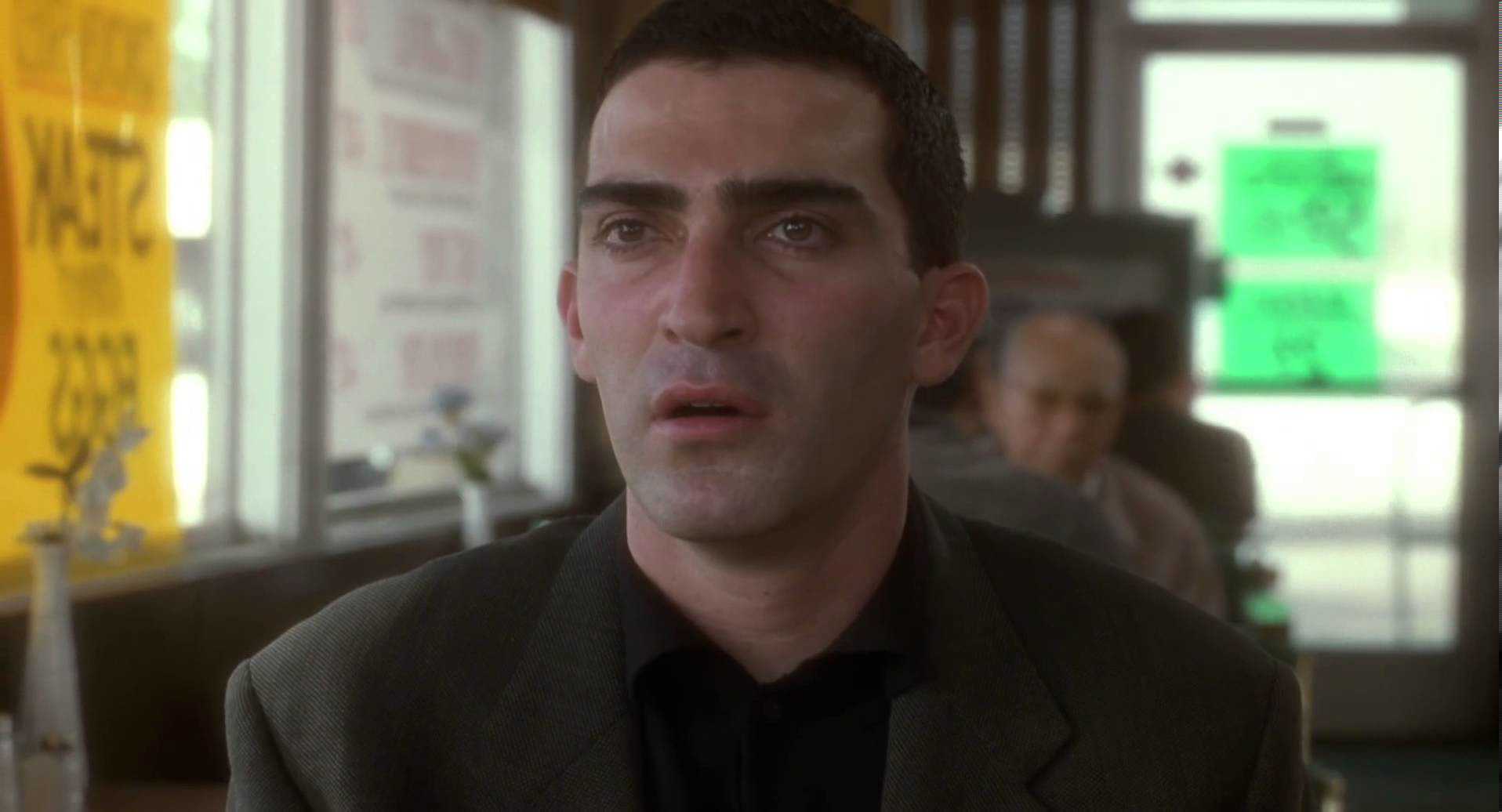

Early in Mulholland Dr., writer/director David Lynch makes a statement that clarifies his larger ambition, in a scene with two men who aren’t shown in any other portion of the film. If you have the subtitles on, or have especially good hearing, you can hear one of these men’s names, uttered in alarm at the scene’s closing. The film has a diverse ensemble: iconic character actor Dan Hedaya sits next to the film’s composer, Angelo Badalamenti, both as mysterious Italian gangsters; Billy Ray Cyrus (yes, the Billy Ray Cyrus) plays a pool man who sleeps with the wife of Justin Theroux’s bespectacled hipster director Adam Kesher; Robert Forster shows up briefly as a laconic LA cop; dance legend Ann Miller swans on screen a few times as the wily landlord of an LA apartment complex. But the scene in question here, between two men called Dan and Herb, featured two unknowns, though, thanks to roles on shows such as “Mad Men” and “Lost,” Patrick Fischler (as Dan) has become familiar to more viewers since the film’s release.

Like the rest of the film, this sequence is an unnerving enigma. Dan details to Herb (possibly Dan’s therapist, though it’s never made clear) that he felt the urge to go to a diner called Winkie’s because of a recurring dream he’s had set in the same restaurant. Herb is in the dream, too, and looks terrified, as Dan discovers “a man” at the back of the restaurant whose face is apparently so scary that Dan dreads ever seeing it in the real world. Herb realizes Dan has gone to the trouble of going to this restaurant and ordering food (which he never touches) to confront his fear. And so Dan, flanked by Herb, descends the stairs outside Winkie’s and walks towards the dumpster, only to discover the man from his dreams, a dark, hobo-like figure who says nothing but whose appearance is undeniably jolting. And then Dan collapses in Herb’s arms, presumably dead from fright. The staging of the scene, and the way the camera (mimicking Dan’s POV) slowly creeps upon the dumpster outside the restaurant, adds to a tense queasiness that permeates the whole of Mulholland Dr.

What Dan does in this sequence goes wholly unexplained. As he approaches the dumpster, there is an unerring sense of doom in each step he takes. Anyone with an even mild awareness of how cheap horror-movie jump scares operate will watch this scene and wonder not if Dan will encounter the mysterious figure from his dreams, but when he will, and if the figure is really as terrifying as he suggests. There may be a lack of surprise in the sequence, but it’s no less unnerving or disquieting, specifically because there is never any clarity regarding why this scene exists. Once the film concludes, it’s easier to piece together the initially displaced and disconnected moments and scenes; roughly the first 2 hours of Mulholland Dr. is an extended dream of its own, concocted by failed actress Diane Selwyn (Naomi Watts, in a true star-making performance, possibly the best of her career) as she suffers both professional and personal rejection. Many, though not all, of the characters from the first 2 hours have notably different identities in the approximation of the real world that we see in the final 30 minutes. For example, Miller’s Coco is no longer a landlord, but Adam’s imperious mother; Adam, now, is perceived by Diane as the major obstacle to her true love, Laura Elena Harring’s Camilla Rhodes. (In the dream world, Harring is a beautiful woman who gets amnesia after a vicious car accident that, ironically, saves her from being killed by two mysterious men driving her around the Valley.) A boneheaded hitman, played by a young Mark Pellegrino, in the dream world is, in the real world, a much more intelligent but no less seedy assassin who Diane hires to kill Camilla when she realizes they’ll never be together. And so on.

Dan and Herb, though, do not re-occur in the final half-hour. (They’re not the only ones; Forster’s cop, nor his partner, played by character actor Brent Briscoe, don’t make reappearances.) There is likely a tangible explanation for their absence: as many people know, Mulholland Dr. began its life as a TV pilot on ABC; the network rejected it, and after talks with international distributors, Lynch expanded the pilot into the feature that was released to wide acclaim at the Cannes International Film Festival in 2001. The scene with Dan and Herb could have easily been an outlier from the pilot that Lynch chose to tinker with to tie into the finale. While the two men don’t reappear, the dark figure from behind Winkie’s does. The restaurant reappears later in the film, for example, in a scene featuring Diane. He (or it) ends up pushing Diane over the edge into insanity and, ultimately, suicide; the two old people with freakishly humorless wide-mouth smiles whom Betty Elms (Diane’s alter-ego) encounters on her trip to Los Angeles are unleashed by the dark figure, first in miniature, then at full size. They descend upon Diane in her dank apartment, laughing maniacally even as she screams in fright before she grabs a pistol out of her bedside table and kills herself.

The number of films and television shows that attempt to replicate the sense of experiencing a dream or nightmare could, itself, fill an entire column. Mulholland Dr. is a rare case of a film that actually succeeds in translating dream logic into a feature; Lynch doesn’t sacrifice an atmosphere of confusion and fear to give detailed explanations of the various plots he presents us with. The film is simultaneously coherent enough on a scene-to-scene basis, and maddeningly oblique. Mulholland Dr. is a series of sequences, all of which are very much like the Winkie’s encounter, in that they feature characters acting in ways that feel simultaneously inexplicable and eminently appropriate. Not every scene is, on its face, terrifying; Adam living out a Hollywood cliche–finding his wife with the pool man–is a sharp and witty moment punctured by his later encounter with an enigmatic Cowboy; Betty’s jaw-dropping audition opposite an older actor (Chad Everett) is uncomfortable in its eroticism, yet totally at odds with the looser and goofy scene where Betty and the amnesiac, known as Rita, practice her lines with cartoonish abandon.

The scene where Dan meets his end behind the Winkie’s dumpster seems, even now, totally removed from the rest of the film. At the very least, we may ask why Diane would imagine the scene occurring, if the rest of the first 2 hours is an elaborate farce concocted in her addled mind. (Betty and Rita go to the restaurant later, seeing a waitress named Diane; in the real world, the same waitress is named Betty.) But there is a parallel in Diane’s dream state, a scene where two characters slowly, carefully approach a grim scene, not knowing what they’ll find. As the mystery expands regarding Rita’s identity and who would’ve tried to do her harm, Betty and Rita hunt down a lead: Rita’s memory of the name “Diane Selwyn.” One call leads to another, until they drum up the courage to go to Diane’s apartment, only to discover she switched apartments with another resident a few weeks ago. So Rita and Betty walk to Diane’s new apartment, open the door, and eventually discover Diane, dead, in total squalor, without ever seeing her face. As with the scene between Dan and Herb, the audience knows Rita and Betty will find something horrifying. By this point, it’s possible that they may find the dark figure from Winkie’s. We’ve already had Adam convene with the folksy Cowboy and the menacing Cowboy, the latter of whom seems to be in as much control of Hollywood as Hedaya’s gangster, so Lynch has established, as he often does, that anything can happen. And Lynch, although he doesn’t indulge in standard-issue horror-movie cliches, quickly establishes a visual language with cinematographer Peter Deming that suggests a monster around every corner, whether it’s a dark figure behind a dumpster, or a dark figure splayed on a dingy bed.

Mulholland Dr., aside from being Lynch’s masterpiece, is one of the most terrifying and haunting films of the 21st century. The faux-Hardy Boys-esque mystery at the core of the picture, much like the one in Lynch’s Blue Velvet, is vastly less important than the atmosphere into which the would-be sleuths descend. Diane Selwyn may not be Betty Elms, but she was once a bright-eyed, naive young girl destroyed by a cutthroat industry and a doomed love affair. The dream she concocts vacillates between being an idealized fantasy and a greater nightmare than her own circumstances. (It’s clear that Betty aces her audition, but the manner in which Everett’s character all but sexually assaults her in doing so is genuinely cringe-inducing.) There is no clear solution to the film, no enigmatic blue box that can be opened with a strange little key. But even the most discordant sequence can provide a slight bit of insight into Lynch’s ambitions with this singular masterwork.

One thought on “The Unnerving Dream Logic of “Mulholland Dr.””

Fischler’s character actually does appear in the final half hour. Diane sees him at the cash register of Winkie’s diner when she’s finalizing the hit on Camila.

I think I’ve pretty much “figured” the movie out. Almost all its elements make perfect sense so long as one doesn’t get distracted with its constant tonal shifts and odd, little Lychian sequences. It’s all perfectly logical or at least it makes perfect dream/fantasy logic.