When Bernardo Bertolucci’s Last Tango in Paris was first released in 1972, it garnered considerable controversy, with many calling for censure and others praising it for its graphic sexuality. Considering how difficult an experience it is, even now, no wonder. Skipping past the pathetic eros, the film takes us to the blackened heart of a man at the edge of a cliff, ready to jump and take everyone with him. More than that, it says that we are all on that cliff, as though every breath of optimism chokes for a moment, knowing that the dark cloud of destruction hovers gleefully behind us.

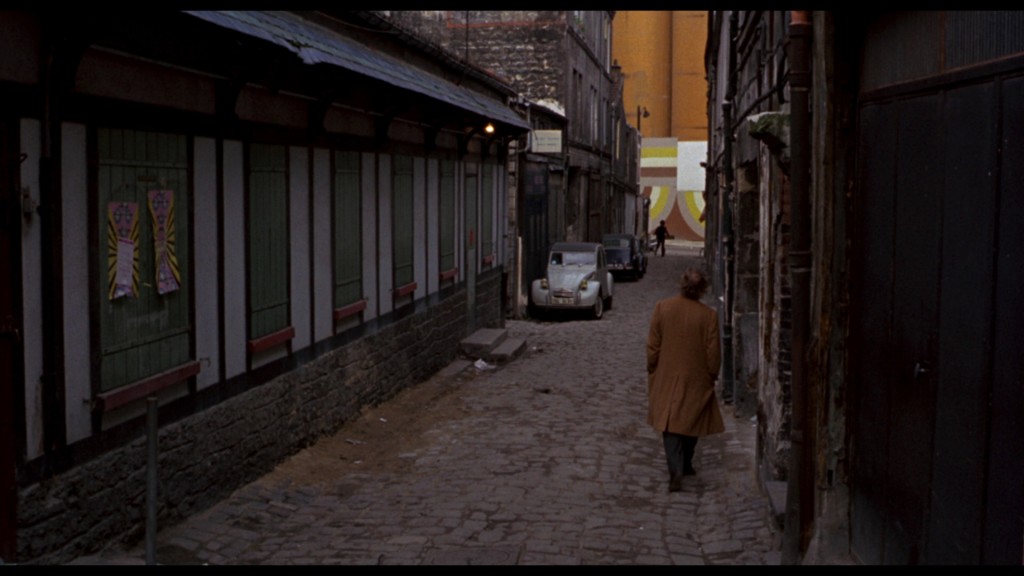

Paul (Marlon Brando) is an American in Paris, squirming beneath the giant clanking screeches of a train above him—a train that becomes a rhythmic force that crushes all silence and thought as its passengers travel casually to their next locations. Under that elevated structure, this man walks slowly. Brando consistently sports a look of confused devastation—the bewildered moment after the moment of shock—staring into something deeper than the sidewalk in front of him, looking for something to rise up and save him. One day, that saving angel, Jeanne (Maria Schneider), walks by. Though lasting only a few moments, this simple sequence is one of cinema’s great openings.

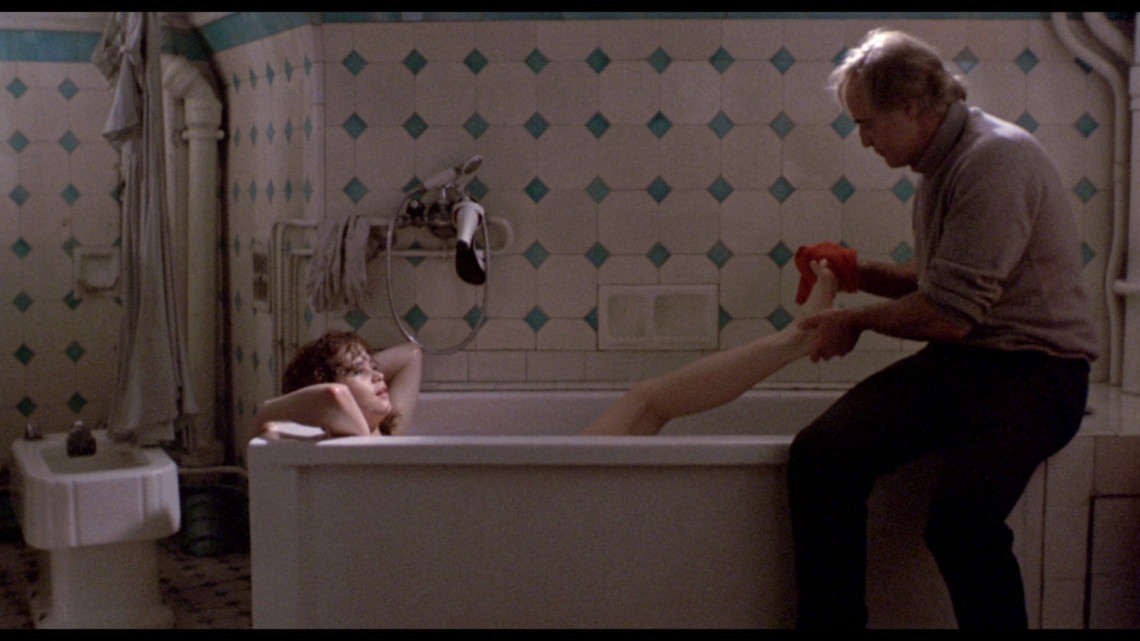

We soon learn the source of his angst: Paul’s wife, Rosa (who we never meet alive), had an affair with another man; later, she killed herself in a bathtub. Now, Paul copes with those two betrayals by sharing, no, imposing his devastation on everyone around him. When hit with death, our system will go through a mourning process, whether or not we ourselves do. Our loved one dies, and a spiritual carcass forms within us, one that must come out eventually. Relief should be the end result of grief—but in Paul’s case, it is rage.

He meets Jeanne in a condemned apartment. In an artificially sweetened Hollywood romantic comedy, she would pull him out of his misery and they would live happily together. Instead, Paul rapes her. When consumed with anger, there is a sick satisfaction we get after we traumatize someone else—a type of relief mixed with the blood-lusting satisfaction of conquest. That is Paul’s expression as he walks out of the apartment, adjusting his coat, after plundering her.

She runs away, but keeps coming back to him, like a child seeking a guardian. He refuses to share or let her share anything about their biographies. As though he has a clean slate with her, he is free to be two men: monster and mouse. He wants to destroy her: physically, emotionally, every way. At the same time, he wants to humor her and guide her, like an old man with a young naive student. That is the behavior of a predator with his Lolita, a lion with his gazelle.

Bertolucci’s characters speak through triangles: either a man with two woman, as in his 1987 film The Last Emperor; or a woman with two men, as in The Sheltering Sky (1990). Here, Jeanne is a young woman in the giant world. We do not know much about her except that she is a child at heart. But, we know her through two men: Paul and her fiancé, Tom (Jean-Pierre Léaud). Both have a single purpose with her: abuse and exploitation.

Tom is a director using her as the co-star of his film. He catches her each time she leaves Paul, broken and lost, requiring her to get into persona without a moment to prepare. Their conversations resemble real conversations between a bride and groom. They are performances, however, and we are not the audience members, but voyeurs peeping in. When she doesn’t cooperate, he beats her and she eventually succumbs by hugging him. Hers is a story of violation; “rape” is the only appropriate word here. One man privately dismantles her body and her being, while the other costumes her and shows her off to the public. If she has any humanity in her, these two men seize it for their own appetites.

Western Modernity has accomplished the task of making us all kings of our worlds in the big city; this in itself is neither good nor bad. The great invention of modernity—the train—brings others into the world to bask with us. The result is a metropolis where we can feed any appetite we’d like, with any level of privacy or publicity. But the human appetite is one that cannot ever be completely satisfied forever. Bertolucci’s film suggests that our unquenched appetites lead us to either present a version of ourselves to mask the broken soul underneath—a “performance,” in essence—or simply to fall into despair.

Brando’s artificial manner of speaking throughout the film demonstrates humanity’s performative side. The actor’s method in his big 1970s films—The Godfather (1972), Superman (1978) and Apocalypse Now (1979)—was to read off cue cards rather than memorize his lines. There was always a deliberate quality to his accents, evident in Don Corleone’s strain and Jor-El’s articulated verbiage. In Last Tango in Paris, Brando’s Paul may not be in front of Tom’s camera, but his every sentence has a rehearsed quality. It is not as though he is reading cards so much as he is reciting from some discarded notebook in his mind containing his reflections on a wretched life. When we finally meet his dead wife, he speaks to her as a man fueled with fury, but displacing it with a prepared speech.

Ultimately, though, despair is the most consistent feeling coursing through Last Tango in Paris. According to the film, even in a state of despondency, our appetites do not cease, instead unrelentingly commanding us to satisfy them. As a result, despair perpetuates itself into destruction and self-destruction. In the final scene, as he stands at a balcony looking to the big city, he takes out his gum and sticks it on the ledge. Jeanne sits in the apartment making comments about him, either as a potential eulogy or a police report. We wait for him to jump. Really, though, it doesn’t matter what he does. In the end, we know very little about him or her, except that they are two people who were devoured by their harsh life experiences. Worse, it is unlikely that anyone would grieve for them.

This essay is in light of the Bernardo Bertolucci’s retrospective at the Castro Theater this Saturday, October 18th. Buy tickets here

One thought on ““Last Tango in Paris”: Basking in the Bowels of Human Discontent”

The challenge I gave myself was to write an essay about a graphic movie without looking at anything graphic.