Editor’s note: We are thrilled to announce that MUBI, the curated online cinema that brings its members a hand-picked selection of the best independent, international, and classic films, is now sponsoring Movie Mezzanine. One of MUBI’s current selections is Junun, from Paul Thomas Anderson; you have until Saturday, November 7 at midnight to check the film out, as well as the rest of MUBI’s selections, with our promo page.

By any normal rubric, the 54-minute Junun is a minor entry in Paul Thomas Anderson’s filmography. Indeed, the film is so simple that it can provide its own synopsis at the top of the film in a brief text crawl: shot in Mehrangarh Fort in Jodhpur, India, Anderson’s documentary captures a collaboration between Jonny Greenwood and a group of Indian musicians as they record tracks for an upcoming album. To be sure, this is clearly Anderson cutting loose, backing off from the ambitiousness of his recent work in favor of a light movie to keep him spry.

Nonetheless, when someone of the director’s skill level decides to indulge himself, the results are always fascinating. The film certainly doesn’t look like a typical behind-the-scenes shoot; Anderson casts everything in rich ochre and bronze, magnifying the opulence of the palace in which the musicians record. Golden arches line doorframes and gigantic, patterned rugs cover the floor, and Anderson regularly takes note of the sheer size of the location, calling attention to what an unorthodox setting it is for music recording. With the windows perpetually thrown open, the risk of ambient sound marks the setup as a far cry from carefully controlled studios.

The open format of the interior permits the director to not simply sit in the corner of a recording booth and watch guys jam. Often, Anderson uses the incongruity of the location to give the camera the impression of having stumbled upon the musicians by mistake before trying to watch without being spotted. Static long shots gaze in from another room, while closer distances are framed in quivering handheld, typically with something blocking the bottom of the frame, as if the camera were peeking over something to get a clandestine view. It’s a playful approach that breaks up the staid, matter-of-fact documentation that characterizes films of this type, and it adds further jolts of excitement to the thrilling musical talent.

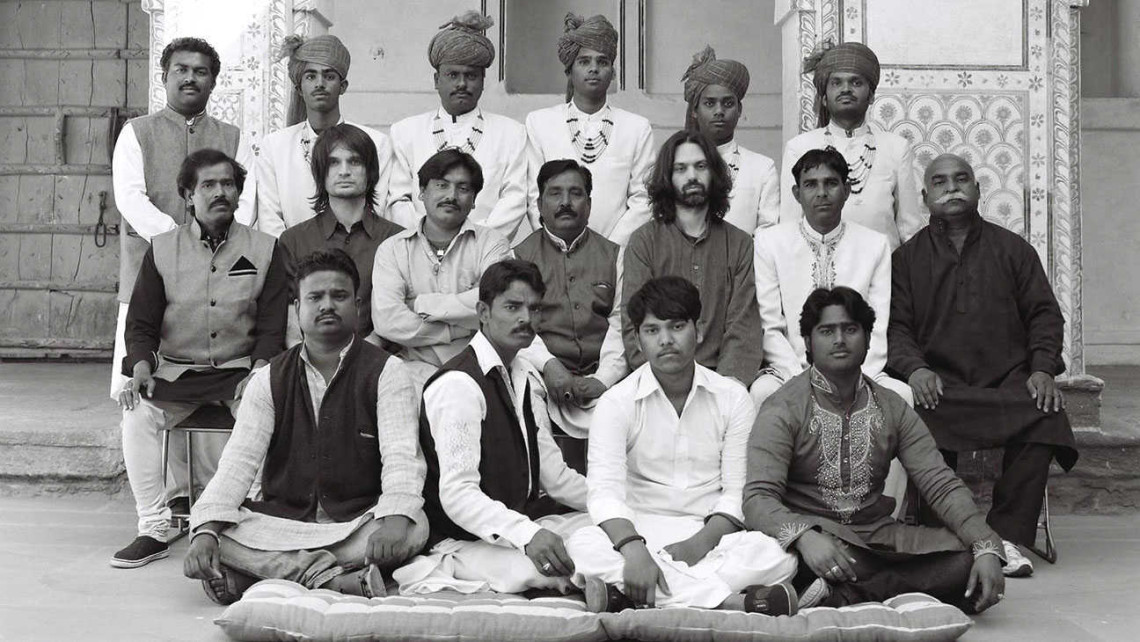

And if this is a departure for Anderson, Junun nonetheless shows some of his trademarks in a compressed form. Just as last year’s Inherent Vice found the director returning to an ensemble format after several features focused on small casts, the documentary prefers group shots to individual spotlights, the better to reflect the collective interpretation and interplay of the music. Instead of pulling out all the stops and unleashing some of his most elaborate camerawork to capture the musicians, however, Anderson finds cheap and unobtrusive workarounds, like 360-degree pans that always manage to work around to a certain musician just as they launch into a solo. It’s a simple trick, but one that establishes a deliberate lack of hierarchy and pulls focus onto the tacit, intuitive communication between professional musicians.

At times, the camera pushes right past the players to soar out one of the windows, at which point drone cameras take over and rise over the looming fortress. These abrupt moments of expansion allow the film to take in the area outside the recording and to actually delve into the world that the musicians invite inside by leaving their rooms open. Anderson captures scenes of tradition and modernity, from a hawker tossing meat to his birds on one of the castle rooks to one of the trumpeters heading into town to buy an electric keyboard, banal observations that give an impression of local life without exoticizing it. The move from the intimate to the cosmic inverts the motion of Magnolia, which constantly bends its head down from the heavens to watch the little people below, stressing the ultimate triviality of their explosive melodrama. Here, the small interactions of the musicians prefigure the entire outlook on how larger groups and systems are related.

Anderson’s last three films have taken as a core concept the extent to which environment informs human nature, from There Will Be Blood’s vegetative and moral wasteland to Inherent Vice using L.A.’s desert outskirts to show the same corruption being given a corporatized mask. Here, however, the director stresses a positive connection to nature, one in which the traditions and surroundings emphasize the spiritual unity of the music. There are no stars in the film, least of all Greenwood, who gets less isolated screen time than anyone. What Anderson has crafted is one of the most beautiful (and beautiful-looking) tributes to artistic collaboration, which he presents not only as the ideal form of creative expression, but as a microcosm of utopian cooperation.

If you’re interesting in watching Paul Thomas Anderson’s Junun on MUBI, use your Movie Mezzanine coupon for an exclusive discount and access to a breathtaking library of cinema!