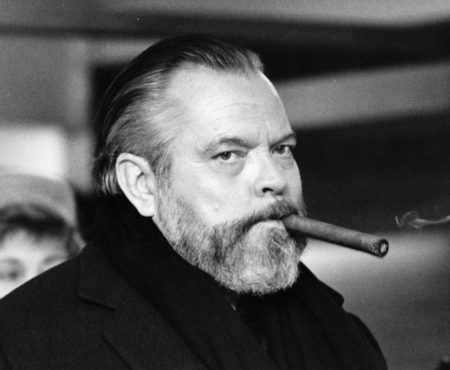

Editor’s Note: Today we’re proud to present readers with an exclusive passage from F.X. Feeney’s new book, Orson Welles: Power, Heart, and Soul, where he discusses the director’s relationship with The Magnificent Ambersons. Feeney’s book is an essential study of one of the most iconic and influential American filmmakers, director of such films as Citizen Kane and Chimes at Midnight. You can purchase Feeney’s book now at The Critical Press.

This ending of The Magnificent Ambersons would most likely have come to us intact had Welles not flown to Brazil on a mission for FDR. He took a print of his 131-minute director’s cut with him, having secured an agreement that Robert Wise would be sent along later to work on it with him, but this promise was never honored. Many of the film’s most ardent admirers have wondered, bitterly, what devilish impulse could have compelled Welles to even risk leaving his masterpiece in the lurch and trap himself ten thousand miles away in South America.

What intruded on Welles’s brief season in creative paradise was the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, on December 7, 1941. For a giddy moment that Sunday, many radio listeners blamed him. One New Jersey man angrily phoned the switchboard at CBS when he heard the first reports: “You bastards fooled me with that Martian stunt, and I’m not falling for it twice!” In private, FDR teased Welles about “crying wolf.” On a more serious level, the outbreak of war reactivated Welles’s dormant political self and energies. On the eleventh of December, he took a break fromAmbersons and traveled to Washington to volunteer his services.

Nelson Rockefeller, the wealthy liberal who was later governor of New York and vice president under Gerald Ford, was then just another in FDR’s orbit, with his own eye on the White House. He was a longtime admirer of Welles, a major stockholder at RKO, and he had a proposal. Would Welles be willing to make a film, immediately, in Rio de Janeiro? With a war to be waged in Asia and Europe, it was imperative that the U.S. form strong alliances with the nations of South America. Brazil and Argentina were being courted by Hitler. There was a need to stop that in its tracks with some cultural exchange. How about a film? Don’t do it, one aches to tell him. Welles would later claim that he resisted the idea, but FDR personally prevailed upon him. Perhaps—it was three days after the attack. The world had changed overnight. Welles had big ambitions. If FDR said two words to him (“Say yes,” for instance), could he have said no?

Okay—a few weeks in the sun, filming revelers at Rio’s carnaval. Welles secured a promise of three hundred thousand dollars in government funding to defray RKO’s risk. (The studio provided for the film at a budget above a million dollars, but this fact did not emerge until Joseph McBride unearthed it in 2006.) Schaefer in turn guaranteed that editor Robert Wise would be flown to Rio with a workprint of Ambersons. There was as yet no script for the Rio project, but in the wake of dealing with Charlie Chaplin he had toyed further with the notion of It’s All True—reenactments of stories taken from newspapers. He had already sent director Norman Foster to Mexico to film the tale of a boy and the bull he saves from the bullring—My Pal Bonito. A segment Welles conceived about the history of jazz could easily be reworked to suit a history of Brazil’s indigenous music, samba. Rockefeller approved, and by late January Welles was on a plane to South America, where a terrific story found him. An article in the December 8, 1941, issue of Time magazine told of a recent political uproar in Brazil.

Four men, fishermen from remote Fortaleza on Brazil’s north coast, had lashed together a raft from six logs, and sailed it 1,650 miles without a compass to confront Brazil’s dictator Getulio Vargas with the desperate conditions of their lives. Word of their voyage spread south as they stopped in coastal villages and cities to eat and sleep. By the time they arrived in Rio Harbor, they were already national heroes. Their leader was a leather-faced peasant with an incandescent smile, called “Jacaré”—born Manuel Olimpio Meira. His charismatic simplicity caused him to be lionized by the Brazilian public. Photos survive of Jacaré speaking with Vargas—the dictator looks a bit squeamish as he attempts chitchat with this more self-evident leader. Once Welles landed, he phoned RKO. He now had a factual and fully-fledged dramatic idea, and could shape everything he filmed around its powerful center of gravity.

How this modest, upbeat lark of a project managed to ruin Welles’s Hollywood career is an important mystery. Misfortune collided upon Welles from several angles, to maximum effect. The Magnificent Ambersons was given a sneak preview in Pomona, California, to a rowdy Saturday night audience whose younger denizens squawked “Georrrge? Georrrge!” in crude imitation of Agnes Moorehead. George Schaefer (seated there in the dark among them) suffered with each catcall, as if they were heckling him by name. Back in the boardroom at RKO, there were maneuvers underway to fire him. To counteract these, Schaefer regretfully enforced a recent adjustment in Welles’s contract allowing The Magnificent Ambersons to be recut at the studio’s sole discretion. When Robert Wise did not come to Rio, Welles sent flurries of wires north, suggesting cuts and lobbying passionately to save certain scenes from the shredder, especially that delicate ending. It was all he could do to keep from boarding a plane—but he was honor-bound. (“I couldn’t walk out on a job which had diplomatic overtones,” he told Leaming. “That’s what made it such a nightmare. I couldn’t walk out on Mr. Roosevelt’s Good Neighbor Policy.”) His highly-sexed relations with the Brazilian people were another, scandal-baiting distraction, and his open fascination with samba culture, voodoo, and Rio’s ghetto-dwellers (all sensuous, rebellious embarrassments to Dictator Vargas) placed him on a collision course with the regime, which in turn embarrassed Rockefeller, back in Washington.

“Nobody was ever more cowardly in the world than Nelson,” Welles told Leaming. “He didn’t want to be near anything that was under any kind of shadow.” Rockefeller quizzed his sources at RKO about the silent, unedited footage that had thus far been shipped back from Rio. “Just a bunch of jigaboos, jumping up and down,” he was told. And so he pulled the plug, reneging on the three-hundred-thousand-dollar share that the government had promised.

Rockefeller viewed himself as a patron of the arts. He admired Welles and championed him, back when he was a stockholder at RKO—but if Welles was really serious about politics, that made him a rival. “From a very young age,” his brother David Rockefeller recently recalled, “Nelson wanted to be President of the United States. He made no bones about it, ever, and everything he did was done with that goal in mind.” The way he left Welles for dead (politically speaking) over the making of It’s All True was royal hardball of a sort Shakespeare understood only too well, and which Welles highlights in Chimes at Midnight, when two would-be Kings face each other in single combat. “Two stars keep not their motion in one sphere,” Henry V warns Hotspur, who lightly smiles as he replies, “Then it is time to end the one of us.”

On May 19, 1942, as these many storm systems were brewing to perfect pitch, Welles commenced filming Four Men on a Raft. The day’s task was to reenact the triumphal entry into Rio. They worked all morning, using Technicolor stock, and got exuberant images of Jacaré and his men, ably soaring across the water on their primitive vessel. (Jacaré’s beacon of a smile beams across great distances in these snippets, straight into Welles’s lens.) The day continued well—and as they progressed, staging these scenes in reverse order, production moved into the Atlantic. There were two beaches—a safe one inside the Amazon’s estuary, and a more dangerous one patrolled by sharks on the ocean side. Jacaré and his men missed Welles’s signal, and made for the wrong beach. The raft capsized. Three men surfaced and scrambled to safety, but one disappeared—Jacaré. They never found him. He was presumably taken by a shark. The whole of Brazil plunged into mourning at the loss of this man, and many (prompted by the Vargas regime) blamed Welles.

The new regime at RKO, eager to hang onto its South American distribution after this disaster, granted him grudging permission to complete Four Men on a Raft. With the footage they had of the arrival, the voyage could be reenacted simply, using a stand-in for Jacaré. Welles, his producer Richard Wilson, and a skeleton crew spent the next few weeks making this happen.

The villagers knew better than to blame Welles for their loss—they could see he was sincere about observing their lives, and sharing them with the world. Welles filmed women weaving. He filmed the men building rafts and putting them out to sea, the cycle of a day, and a million days. He staged a wedding and a funeral—not as a direct reenactment of their leader’s tragedy but certainly in the symbolic sense of a more workaday, no less terrible variety in which a young bride loses her new husband to a drowning. The vast procession Welles staged has an “unrehearsed epic” quality. These people of Fortaleza move in a wordless rhythm with one another, while Welles and his cameraman, George Fanto, reveal their innate ways of being on their behalf.

This is the most beautiful footage, as footage, Welles ever committed to film: breathtaking in its vistas, heart-stirring in its humanity. It’s All True endured many misadventures after Welles returned to the states. RKO was no longer interested in it. The highly publicized debacle jinxed film deals. Suddenly, he was “unreliable”; the guy who blew a ton of money in Rio and came back empty-handed. He optioned the footage for a time, but missed a payment amid the high cost of making a stage play out of Around the World in Eighty Days. The footage was taken over by RKO and—Welles long presumed—destroyed. It turned up a few weeks before his death in 1985, in a vault at Paramount. In 1993, his producer Richard Wilson collaborated with critics Myron Meisel and Bill Krohn to weave these fragments into a documentary, titled It’s All True: Based on an Unfinished Film by Orson Welles.

A bit of unexpected magic occurred when Four Men on a Raft was finally assembled. Jacaré is there in the final shots—big as life, vibrant, smiling as if he knows a joke so good it can’t be put into words.

You can also purchase Orson Welles: Power, Heart, and Soul on Amazon.

2 thoughts on “How Orson Welles Lost “The Magnificent Ambersons””

F.X. Feeney is one of the most underrated writers about film working today. I really like guy as I found him to be an engaging personality in the movie about Z Channel.

Pingback: The Magnificent Ambersons Supplemental Reading | Brattle Theatre Film Notes