David Lynch’s Blue Velvet is a film containing all the ingredients of a Lynchian nightmare without venturing too deep into abstraction. It’s because of this that the film isn’t one of Lynch’s more heavily dissected works, but that doesn’t make it any less substantial than his dream-narratives. The film remains a classic in its own right: a perfect marriage of classically composed storytelling and disturbing surrealism. But perhaps more importantly, its influence in storytelling still resonates to this day, as its themes and ideas are still being used and reused after all these years.

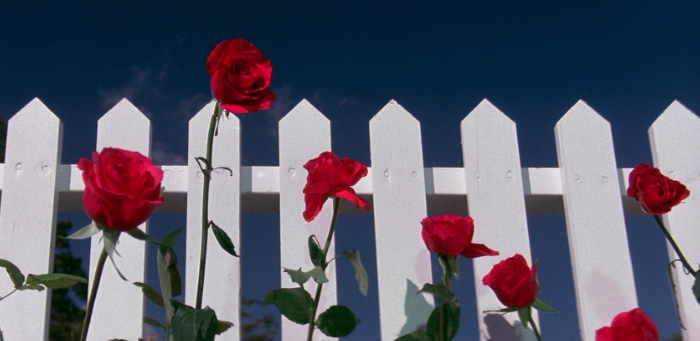

Blue Velvet is about many things, but it primarily strives to show viewers the then-rare portrayal of sinister secrets lurking within the cracks of a seemingly innocent, Rockwellian, American small town. Seedy underbellies were certainly not an uncommon trope at the time, what with the many film noirs of the ’40s and ’50s set within the shadowy alleyways of “the big city”; but a new setting made a big difference, and the logging town of Lumberton, North Carolina made the stark contrast between the American Dream and the American Nightmare that much clearer, as evidenced in the film’s now famous opening montage, in which menacing insects burrow under the pristine white picket fences of the freshly trimmed suburb.

This idea of small-town American life holding dark secrets has rippled on throughout our culture. Many commonly mistake Lynch’s other work, the television series Twin Peaks, to be the main instigator of this concept in American popular culture. Twin Peaks was, of course, more popular than its more explicit cinematic counterpart, but upon re-watching Blue Velvet for a recent article, it’s hard to view Twin Peaks as anything but a weekly, serialized extension of the film’s core themes. Nowadays, it’s impossible to watch small-town set film noirs or crime procedurals — whether it be films like Winter’s Bone or shows like The Killing and Desperate Housewives — without hearkening back to when Kyle MacLachlan’s Jeffrey Beaumont found a severed ear just lying in an abandoned field, almost as if it was waiting for him.

Blue Velvet‘s vision of the darkness corrupting suburban America from within may not be a comforting theme to grasp, but it is a vital one, and it’s easy to see why it is still employed as a common trope in pop-culture. Many of Lynch’s films were rather critical of American culture, and while that social commentary technically began with Eraserhead‘s Cold War influenced nightmare, it was Blue Velvet that really cemented Lynch as a distinctly American pop-culture influenced filmmaker, carrying over to the pulpy, violent romance of Wild at Heart and the neo-noir experiments of Lost Highway and the Hollywood-set Mulholland Dr.

The concept of the American Dream will always remain a constant in popular culture, and while many pieces of fiction do acknowledge it for what it is — a dream, and nothing more — Lynch takes the “nightmare” half depicted in hundreds of film noirs, and puts emphasis on the “nightmare” aspect, to the point of almost being literal. He tints the two sides of Lumberton with a surreal, subconsciously-fueled lens. Its white picket fences are pristinely painted, the roses beside it are a deep, luscious red, the water squirting out of the sprinklers of a freshly mowed lawn brings out a faint yet colorful rainbow, all while a man stands on the side of a moving firetruck waving directly at the camera with a humble smile on his plastic face.

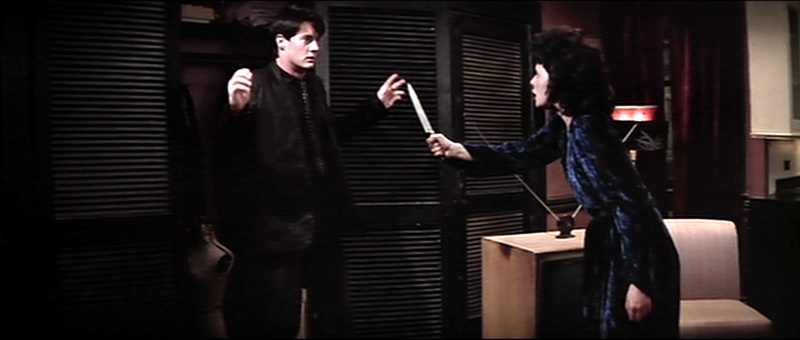

But most important of all is Lynch’s depiction of the Nightmare World. Though this is easily one of Lynch’s most straightforward films, that doesn’t make it entirely absent of dark, surreal imagery. One image that always stuck with me was of the Yellow Man, shot in the head yet standing upright like a motionless zombie. Meanwhile, the rest of Lumberton’s nightmare half stands in stark contrast to the suburban paradise of the film’s opening montage, adorned with deep shadows, blood-red curtains, and a swarm of deeply depraved characters feeding off the light of the Dream. One of those characters, Dennis Hopper’s gloriously demented Frank Booth, is a personification of the pure evil of the Nightmare, and one of the most memorable and uncomfortably sinister screen villains of all time.

Lynch, a long-time advocate of transcendental meditation, has always firmly believed that dreams are the key to understanding the unexplainable aspects of the everyday world. Blue Velvet is one of those dreams. A dream about how evil manages to find ways to burrow into the purest of places and the most innocent of hearts. That may be why Blue Velvet has ended up influencing so much of the fiction following it, and still manages to emotionally connect with viewers. It is a concept that attempts to explain the unexplainable, in all of its forms (Desperate Housewives included).

While the cultural concept of the American Dream may continue to evolve, it remains able to become corrupted by forces and urges beyond our control or understanding. Blue Velvet, nor any other film, can never offer a concrete explanation for how this evil can taint our well-intentioned American ideals, but with its hopeful ending — more hopeful than the standard for David Lynch — it does give us something that can only be achieved through fiction and dreams alike: a catharsis.