The 1941 musical Sun Valley Serenade ends with a sequence that blends fantasy and athletics. Norwegian figure skater Sonja Henie is the film’s centerpiece, leading an impeccable ice ballet on blackened ice. She was the rare sort of woman athlete who was able to transition from a successful sports career to a profitable one in acting, with films like One in a Million (1936) and Second Fiddle. At the height of her fame, Henie was among the highest-paid stars in Hollywood. Her body type was lean, her face was symmetrical, and her demeanor was conventionally feminine. For audiences, she was just another starlet, not an Olympic medalist.

For many women, the ultimate ideal body still comes from our mediated culture. There is still a stigma for athletic women; their bodies, stories, and ambitions are considered “niche,” exceptional, and un-feminine. While sports movies are an enormously popular genre, stories about women athletes remain rare because unlike their male counterparts, women athletes don’t get the same level of opportunity to transition their success from sports to showbiz.

Henie represents the typical female-athlete-turned star in Hollywood. Her class, beauty, and sport maintain, rather than confront, the status quo. Skating reflected the upper-class leanings of most respectable female sports of the era, where money could buy you the privilege of crossing into more traditionally male realms. As Anna Clark noted in a Grantland piece, “Hollywood’s Lady All-Stars: Title IX in the movies,” “The graciousness associated with sports of privilege gave females a sort of buffer zone for athletic participation: Wealthy women had an ‘in’ to the world that was otherwise considered anti-feminine.” Sports like figure skating, golf, and horseback riding offered upper-class women a convenient way to participate without sacrificing their femininity.

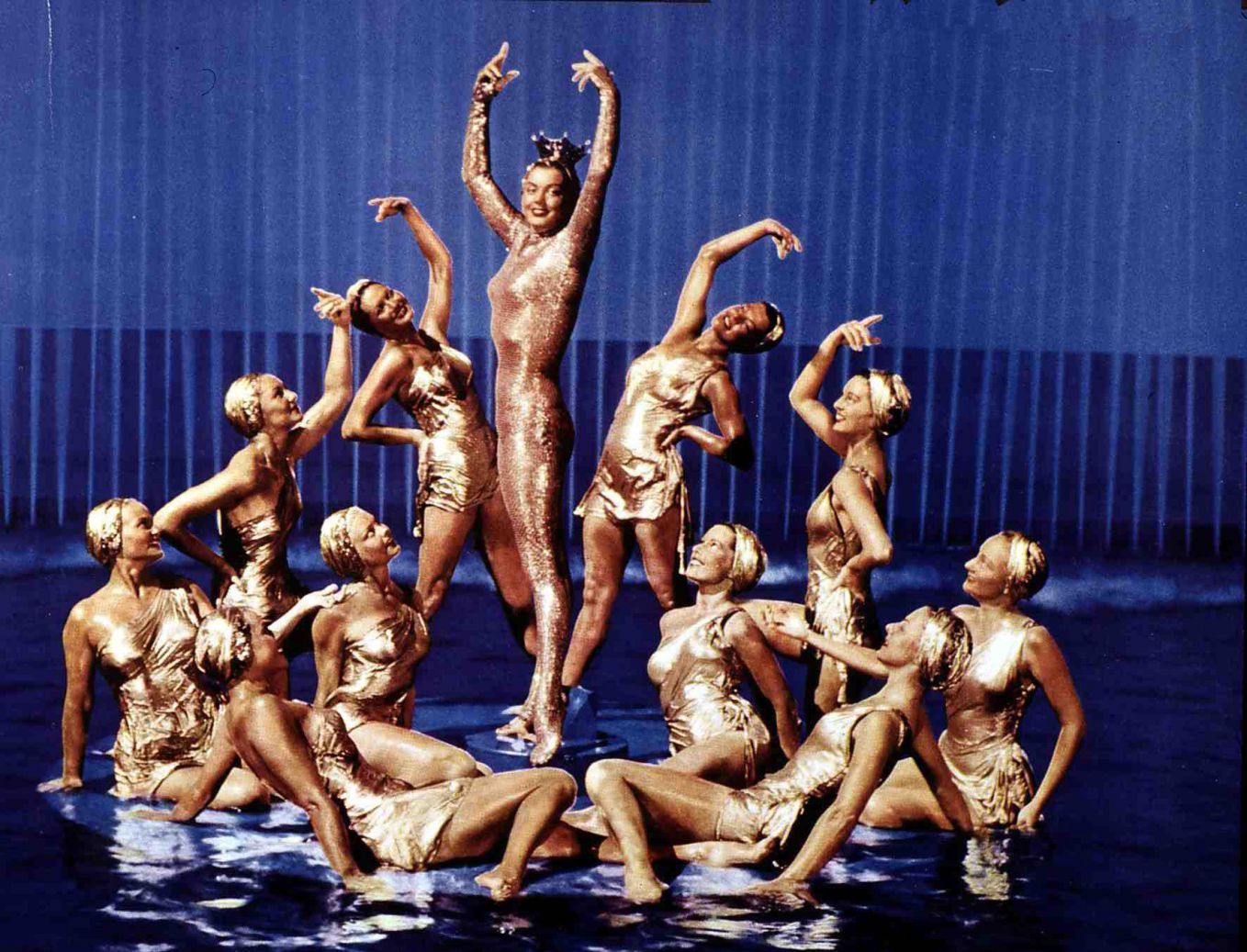

The femininity of post-war Hollywood cinema faced with a crisis. Since during wartime many women left the home to go to work, a new kind of feminine ideal was emerging that challenged the stay-at-home glamour of the 1930s. As one of the biggest stars of the late 1940s, professional swimmer Esther Williams exemplified post-war glamour. With her huge grin, auburn hair, and wholesome persona, she not only looked the part, but reflected a shift in the perception of women as being potentially athletic. Not quite as threatening as the femme fatales of noir, she was able to bridge the gap between the girl next door and a woman with autonomy. Williams was arguably the most successful athlete-turned-actor in the classic Hollywood era.

Unlike many of her contemporaries, she was undeniably athletic; with her broad shoulders and strong thighs, Williams did not look like other starlets. In her films, set pieces were not limited to synchronized swimming performances but tests of endurance as well. While the films certainly exaggerated her femininity—no matter what kind of underwater challenge, she was always in full Technicolor makeup—they offered her the opportunity to demonstrate the strength and resilience required to become a professional swimmer. Williams’ body type was also not quite like anyone else’s at the time, and while she still quite conventionally attractive, her presence provided a small step in expanding the different kinds of body types depicted onscreen.

In Million Dollar Mermaid, a 1952 biopic starring Williams as Annette Kellerman (another athlete-turned-actor), the camera has no problem zeroing in on Williams’ physique. In one scene, Williams walks confidently around the crowded Revere Beach, wearing a one-piece bathing suit. Outraged beachcombers gasp and leer at her uncovered legs. Their point-of-view shots show Williams from the waist down: it’s not just Williams’ legs on display, it’s her muscles.

As we assume the perspective of the outraged beach residents, we are meant to channel their shock and desire. Kellerman was unaware that she was challenging the law with her outfit—she was thinking practically, for the corseted swimsuits of the time were impossible to swim in. While swimming in heavy cloth and a corset was not impossible, the obvious restrictions on breathing ruled out any kind of endurance swimming, especially in deep or unpredictable waters. The leering camera suggests at once a male gaze titillated by female body parts that are normally covered, while it also exoticizes the unfamiliarity of muscular women onscreen.

When Kellerman is arrested for indecent exposure, she defends herself in court, arguing that wearing the corset suit would not allow her to swim. The regulations of decency reduce her mobility and threaten her independence. Million Dollar Mermaid champions her right to be treated with respect as a world champion.

Kellerman came up with compromise: a modified swimsuit that covers her legs and offers enough mobility to swim and dive. The highly publicized case helps jump start her career, which eventually leads her to a successful show at the New York Hippodrome. Kellerman performs at their large 8,000-gallon tank, which could be raised from below for swimming and diving stages. While elements of the film were obviously fictionalized, the story of Million Dollar Mermaid touches on most of Kellerman’s real-life milestones, and she personally approved Williams for the role.

In the film’s major underwater showcase, we see the full range of the star’s strength on display. Million Dollar Mermaid is careful to show that Kellerman’s (and by proxy Williams’) status as “America’s Mermaid” was not something these women were born with, it was something they worked very hard for. Their athletic bodies are symbols of resilience and hard work. Nonetheless, the film shows that Williams is an object of desire. Her femininity is emphasized through the male gaze.

Several decades later, the importance of maintaining femininity for the male gaze was challenged in Robert Towne’s 1982 film Personal Best. The film not only features an incredibly wide range of women’s bodies but attempts to challenge a heteronormative gaze. With a supporting cast that includes real Olympic athletes, Personal Best is a radical departure from the packaged athletic performances of the classic Hollywood era. Cinematographer Michael Chapman’s high-speed camera captures with rippling detail and in equal measure the athletes’ bodies in motion, in pleasure, and in repose, featuring some charged sex scenes and a lot of gratuitous nudity. It’s hard to think of Personal Best as anything but a thesis on women’s bodies.

Patrice Donnelly gives what might be the best performance by an athlete-turned-actor in Personal Best. Having competed in track events at the 1976 Montreal Olympic games, she plays a track star in the film who’s trying to qualify for the 1980 Moscow Summer Olympic games. Sensitive, nuanced, and strong, her performance elevates the tropes of the text into a complex meditation on love, sex, and identity. While she only acted in a handful of films, Donnelly left an indelible mark.

Personal Best is both empowering and voyeuristic—and not only because of its lesbian romance. The intimacy of the film brings us into steam rooms and track fields with the same gusto. The camera lingers on naked bodies, and as women master the high jump, their crotches take the center frame. While the film features athletes who don’t fit the traditional mold of female beauty, the lingering cameras feel fetishistic: an unveiling of the flesh that should be seen as radical and empowering, but which ultimately comes across as leering, bound by perverse curiosity.

It doesn’t seem to be accidental that a film that voyeuristically explores the bodies of athletic women would also be queer. As if the framing of a queer romance gives permission to the viewer to desire the athletic bodies on display. This aspect of the film feels somewhat forced though, as the film falls back onto heteronormative tropes. The camera and as a result, the audience, always takes a perspective of “looking in,” as if we were tourists in a forbidden world.

Personal Best also marks the rare instance of seeing black female athletes on screen. Despite their being in supporting and bit roles, the film goes a long way in offering a surprisingly diverse cast, which is refreshing, given the scant and problematic history of women athletes’ representation in cinema. The film shows a more realistic portrait than most films about or starring professional athletes.

Since Personal Best, there has been a push in all areas of popular culture to feature a wider and more representative range of Strong Female Characters, particularly action cinema. As a result, the bigger influx of women taking on action roles has inevitably meant that some of the most successful women athletes to turn to Hollywood in recent years have martial arts backgrounds. Stars like Ronda Rousey and Gina Carano have found unprecedented mainstream success as athletes before turning to acting. However, in spite of their privilege as conventionally attractive white women, the discourse surrounding their bodies remains complicated.

Take Rousey’s appearance in Entourage (2015), in which she plays a version of herself. Her highly sexualized role is loaded with otherness: her strength and body are presented as inherently threatening to the fragile male egos that drive the film. Rather than being empowered, she is stigmatized; her presence is a punch-line.

Both Carano and Rousey are token “tough girls.” Their roles in the Fast & Furious franchise—Carano in Furious 6, Rousey in Furious 7—are virtually interchangeable, as if they’re fitting a quota for strong empowered women who can never be leads, only side characters. Rousey’s appearance in Expendables 3 (2014) is much the same, and while Carano’s recent performance in Deadpool (2016) feels like a slight step up as she takes on a more dynamic and present role, it’s still very much in the same category of celebrity casting as shorthand for character development.

One exception to these roles is Carano’s performance in Steven Soderbergh’s Haywire (2011), which challenges our idea of femininity and athleticism. A minimalist ode to the action genre, the film’s casting of Carano as Mallory Kane is obviously conditional on her athletic career. However, both the role and performance offer something more. Much in the way films are built around the skills of martial artists like Jet Li, Soderbergh crafts a film in tribute to Carano’s talents. The film is an extraordinary showcase of her athleticism and stands out as one of the best action films of the past 10 years.

Soderbergh toys with our idea of what it means to be a strong woman by offering us a character with the body and experience of a real fighter. Like Ginger Rogers dancing alongside Fred Astaire, she one-ups her male opponents in heels as if to prove she can do the same or better even in impracticable footwear.

Carano’s physical voice was edited in the film’s post-production, causing some heated online debates around the director’s choice to lower her natural voice as a means of disguising her poor acting and exaggerating her strength. Her natural voice, which is not only higher but lighter, almost soft, hints at a more traditional preconception of femininity. “Soderbergh wanted Mallory Kane to be a completely different entity than Gina Carano,” Carano explained. “So [we] did some tweaking.”

A rarity for a film about a woman’s sport star, Soderbergh consciously plays with audience preconceptions about Carano. Rather than use her casting as a shortcut, he complicates our understanding of a strong female presence by manipulating her femininity. It is especially noteworthy as those who would be more likely to recognize this change would be audience members who have followed Carano’s MMA career, rather than cinephiles. The film seems to be asking, “Who is Gina Carano?” Is she a hero? An athlete? A movie star? Is it possible for someone to be all three?

And yes, why not? Studies have shown that the more we are exposed to different body types, the more we are likely to accept and desire them. Hollywood’s myopic vision of femininity, especially as it ties to sports, limits and restricts the kind of bodies we see onscreen. Strict gender roles not only inhibit the diversity of bodies we see but the kinds of stories we tell.

Sports films are among the most financially viable sub-genres in cinema, and yet, it remains a male-dominated genre. The gender imbalance affects sports in real life, too. In the U.S., women receive fewer opportunities to excel in sports than men. This, despite the fact that women’s participation in U.S. college sports has increased by 560% since 1972. Given this skyrocketing increase, it’s a shame Hollywood hasn’t catered to women and girls who are interested in sports, or tried to represent their experiences and role models onscreen.

While it often seems as though the idea of femininity has expanded since the birth of cinema, the difference between the days of Sonja Henie and Ronda Rousey is not particularly significant. Both women represent exceptional athletic skills and strength, but remain safely packaged in a very narrow and strict definition of femininity. If Hollywood has room for men of every size, shape and creed, why can’t there be the same diversity for women?

One thought on “The History of Women Athletes In American Cinema”

Pingback: March in Review – Beyond the Red Room