I. In a profile published by the L.A. Weekly around the release of the 2006 animated musical Happy Feet, Australian director George Miller—creator of the Mad Max franchise, co-founder of Kennedy Miller Mitchell productions, and former medical student—said that he “honestly [saw] no difference between the essential elemental story of…The Road Warrior, Lorenzo’s Oil, and Babe.” This makes sense not just because Miller had a hand in writing all three of those films, but also because they all do follow the same Hero’s Journey’s model of storytelling: a reluctant hero sets out on a journey into the great unknown, confronts good and evil forces, gains wisdom and experience along the way, completes the journey, and returns “home” a changed person. Everyone from J.R.R. Tolkien to Dan Harmon have used Joseph Campbell’s monomyth as a storytelling template because it’s an effective structure that allows for creative breadth without sacrificing narrative coherence.

Miller has directed nine feature films in 36 years and all of them follow this same storytelling template, but his brand of auteurism doesn’t just end at script structure. His personal style pervades every one of his films, from low-budget carsploitation flicks to mainstream family fare. Miller’s style is more difficult to pin down than simply a collection of pet obsessions or recurring visual schemas. It’s more of a general sensibility, one somewhat twisted and outrageous, but also deeply empathetic towards those wayward souls on the journey into Miller’s mind, a place large enough to contain both picturesque farms and Thunderdomes.

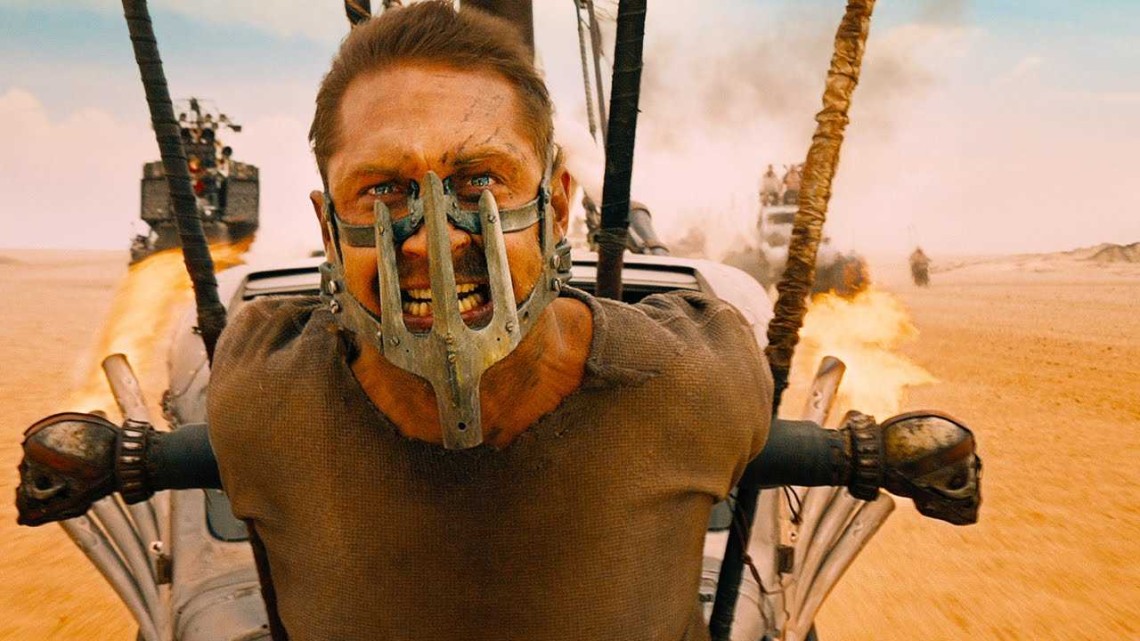

II. Miller’s main obsession lies with placing his mind on screen, shaping universes filled with equal parts immense dread and undying optimism. They are worlds with institutionalized forces that have a vested interest in chaos and destruction, but also contain few unlikely heroes crazy enough to hold onto principles and sanity. Miller’s worlds aren’t rose-colored havens or unrelenting grim factories, but simple environments bursting with endless possibilities for good and evil.The Mad Max films are set in a post-apocalyptic wasteland that takes the shape of suburban highways and desolate deserts. The first Mad Max (1979) focuses exclusively on Miller’s crazed dystopia, eschewing plot and character to instead revel in the fictional landscape populated by gruesome motorcycle gangs and brave warriors. It’s a ballet of gritty, well-choreographed car chases, gruesome deaths, and unchecked vengeance tied together by its protagonist, Max Rockatansky (Mel Gibson), a brave man eventually broken by the world he thought he could control. When Max’s wife is gravely injured and his infant son brutally murdered, he loses all sense of self and conforms to the anarchic lifestyle his universe demands. The last two shots of the film are of Max’s vacant eyes and an open road containing nothing but trouble. Though it initiated a franchise and established a style, Mad Max is arguably an outlier in Miller’s storied filmography mostly because the universe “wins.” The film’s ending features a muted triumph with Max killing his enemies but also giving into his worst impulses, allowing the surrounding wasteland a subtle victory against the forces of good.

The second and third Mad Max films expand on the thrills of the first—more elaborate car chases, more extravagant punk costumes, and fewer lines of dialogue—but adds the hard-won optimism that would permeate his subsequent films. His optimism takes the form of communities, like-minded individuals eager to take on a dehumanizing system. The community in The Road Warrior (1981) is a gang of defenders protecting their oil refinery from gasoline-crazed marauders. Dean Semler’s photography emphasizes not just the barrenness of the desert, but also an open environment for powerful institutions to run roughshod over the meek. But though evil runs rampant in Miller’s world, the film is hardly miserablist; instead, Miller delights in difficult victories. Max helps defeat the gang of bandits through a delightfully insane car chase, and the defenders leave to start a new land, one without institutional supremacy and unchecked violence.

It’s pretty much the same situation in Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (1985), replacing a defender gang with a band of Lost Boys-esque children and a marauder gang with a dictatorial local government. The children are Miller’s most obvious representation of hope in the face of despair: They’re plane crash survivors, abandoned by their parents, and eagerly waiting the return of the Flight Captain to fix their plane to take them to “Tomorrow-morrow Land.” When Max stumbles upon the children after enduring the harsh reality of Bartertown, Miller treats them like an oasis in the desert (highlighted by the gorgeous wide shot of the children standing on a marooned plane) even though Max initially responds to them like they’re a mirage. Max eventually shepherds them to safety, creating another utopian environment free from the dark clutches of Miller’s world.

In his next two films, The Witches of Eastwick (1987) and Lorenzo’s Oil (1992), Miller shifts away from his dystopian comfort zone into worlds that resemble our own. In The Witches of Eastwick, an adaptation of John Updike’s novel of the same name, the quaint Rhode Island town of Eastwick operates as the oppressive system, filled with repressed, gossipy townsfolk eager to snipe at those who don’t conform to behavioral norms. Spurred by the seductive manipulations of the mysterious Daryl Van Horne (Jack Nicholson), our three witches (Cher, Susan Sarandon, and Michelle Pfeiffer) embrace their inner rebels and flagrantly act out against Eastwick with the help of their supernatural powers. In Lorenzo’s Oil, Augusto and Michaela Odone (Nick Nolte and Susan Sarandon) desperately fight against the medical community with its ingrained skepticism towards alternative treatments that might help save their son from ADL, a rare fatal disease. Miller transforms the placid Washington D.C. suburbs into a dark nightmare where a child suffers while skeptics of all forms—nurses, scientists, physicians—shake their head and do nothing. He emphasizes the claustrophobia of hospitals and homes to create the feeling of living with disease without support from the outside world, like test subjects trapped in cages.

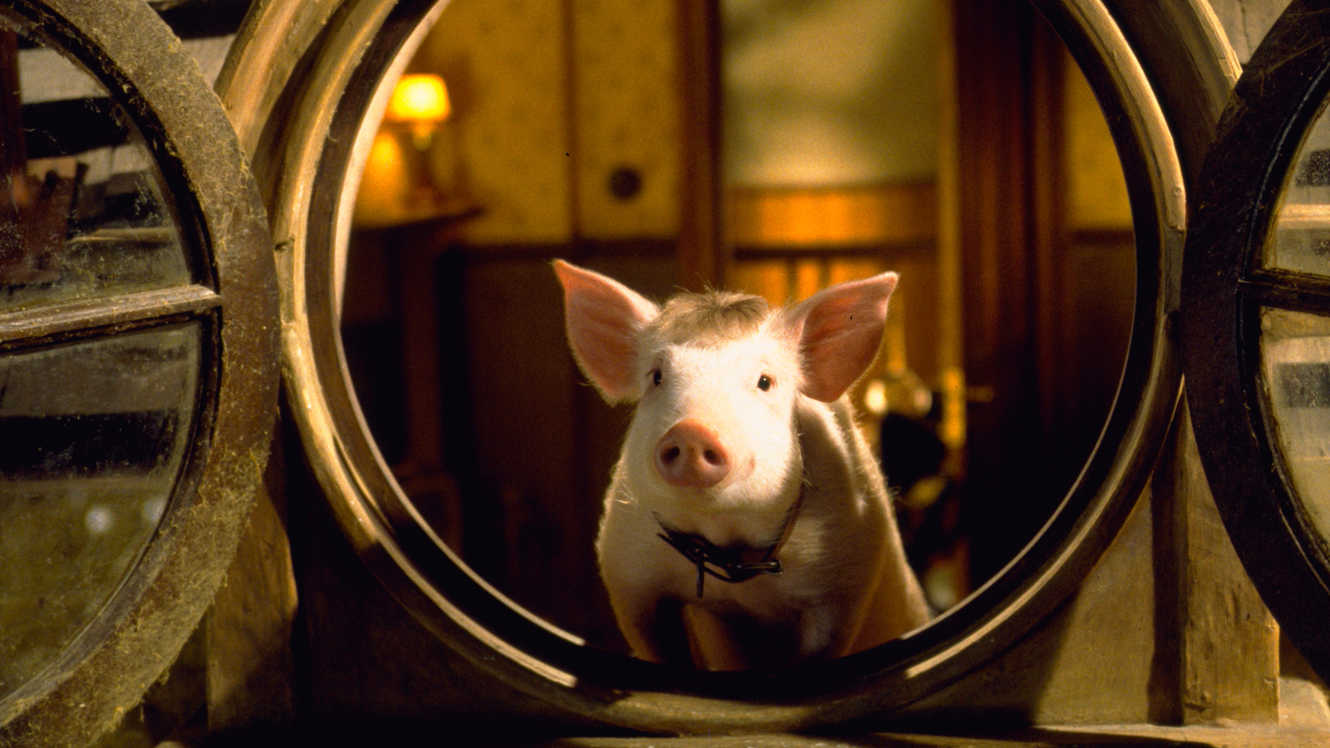

Miller’s subsequent forays into family-oriented films sustained his creative vision. He co-wrote and co-produced Babe (1995), a film about an orphaned pig who’s brought to an unfamiliar farm and acts as its sheepdog to justify his continued existence to the head farmer. After that film’s critical and box-office success, Miller himself took the directorial reins for its sequel, Babe: Pig in the City (1998), which features an industrial urban hell that attempts to crush the spirit of Babe and his fellow strays as they struggle to survive against mysterious specters—manipulative clowns, dangerous dogs, and animal control employees. Pig in the City’s darker tone and more mature, existential themes alienated viewers expecting more family appropriate material, but it has gained new life as a cult film because of Miller’s commitment to his vision of a frightening world.

In the Happy Feet films, the Antarctic floor is under siege by internal prejudices and external manipulation. In the first film (2006), Mumble (Elijah Wood) struggles against a population unwilling to adapt to new forms of mating expression, forcing him to eventually confront the elder population and demand acceptance and tolerance. Though the focus of Happy Feet Two (2011) is a bit more scattershot, its greater emphasis on sustaining community against sustained environmental trauma to the Antarctic floor gives the film resonance. While the Happy Feet films are designed for easy consumption, they still feature worlds that allow for cruel, bankrupt systemic oppression as well as communal optimists willing to take on the system, even if said system is as enormous as the catastrophic effects of global warming.

III. Miller’s films feature numerous other touchstones. His fidelity to visual storytelling renders complex plots and punchy dialogue unnecessary, focusing instead on sweeping camera movements and dynamic choreographed action to drive his films. Miller’s love of practical effects in his action films ground his bombastic vision in the realm of the possible. His keen sense of color and costume design not only enhances the creative breadth of his filmic worlds but also shortcut needless over-characterizations of his characters (half of Mad Max’s characterization is in his dark-toned street warrior garb).

But it’s in Miller’s unique world-building where his true auteurist sensibility lies. Miller injects the feeling of lived history into his worlds through an expansive scope, but also through collective trauma—everyone in Miller’s films are in some way connected by lingering fear of their surroundings. These worlds capitalize on our deepest fears while also allying said fears by confirming the persistence of hope within hopeless environments. It’s the settings that define Miller’s characters—Mad Max and the dystopian wasteland, the Witches and repressed New England society, the Odones and the skeptical medical community, Babe and bleak urbanity, the Emperor Penguins and their crumbling Antarctic infrastructure. They embody and react against their landscapes and the social milieus that permeate them.

Miller, who turned 70 two months ago, once described filmmaking as an “avocation, not a vocation,” claiming that his career is driven more by artistic impulses than by job stability. This is coming from a man who dropped out of medical school a few weeks before obtaining his degree because he wanted to make movies. As a result, he works at a measured pace (read: whenever he wants), unmoved by the sheer prospect of filming a movie just for the hell of itself. Today, Mad Max: Fury Road rides on a wave of positive reviews, many of them praising Miller for bring a personal vision to bear on big-budget property—as if we expected anything less from him.

One thought on “The Twisted, Outrageous, and Empathetic Mind of George Miller”

Really good article summing up Miller’s filmography and showing the thematic through line in his films. It sounds like Miller wants to make more movies now, including a whole new Mad Max trilogy. I’m more excited to see what kind of stories he wants to put on screen that aren’t set in the world of Mad Max.