When David Lynch started making films, he wanted to bring his paintings to life. At the time he was attending the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and discovered the possibility of making his still paintings move. He began producing short films, which eventually led him to break into features when he was offered the opportunity to study at the American Film Institute. Before he started producing feature films he lay the foundation for his aesthetic and philosophical style, which draws from art history and his own American background. These early years are charted in the new documentary, David Lynch: The Art Life, which recently screened at the RIDM film festival in Montreal.

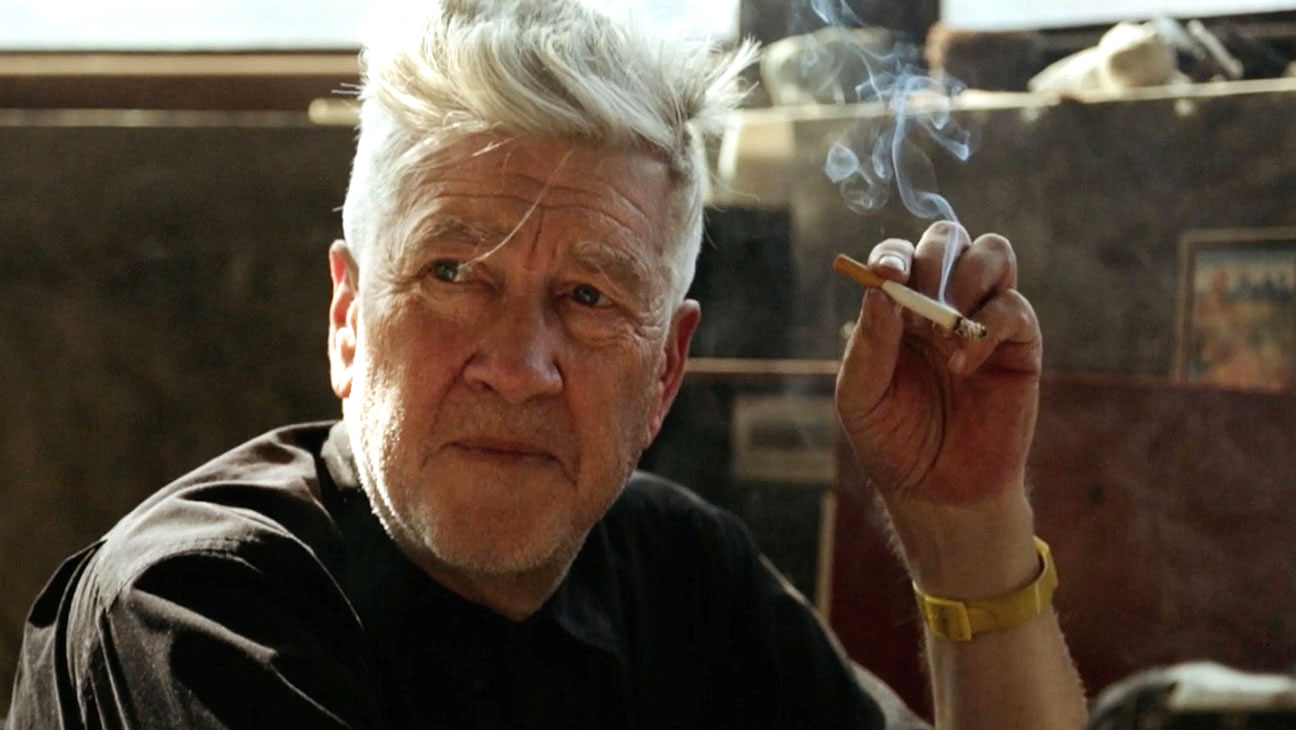

Lynch’s life as a visual artist takes center stage in The Art Life. Using audio recordings, archival footage, and images of Lynch working in his California studio, the portrait of a painter emerges. His art and his voice come to dominate the film’s visual and emotional texture, embracing the off-the-cuff cadence of Lynch’s storytelling with its abrupt confessions matched with tangential anecdotes and vivid evocations of hauntings visions. It seems like a blessing that Lynch has somewhat disappeared from public life since 2006 or else he would have likely befallen a similar fate as Werner Herzog: reduced to a meme. As it becomes increasingly evident that Lynch and artists like him are consumerized as bite-sized phrases and cute anecdotes, his work has lost little of its luster to unnerve normality.

Lynch’s childhood plays a large role within the film. It was mostly happy, pierced by bizarre, dissonant images. Lynch recalls as a young child playing outside with his brother just after dusk when a stunned, naked, porcelain-skinned woman with a bloodied mouth wandered past them in their Idaho neighborhood. Images like these punctuate Lynch’s self-proclaimed idyllic childhood and pull back the veil on his aesthetic obsessions. Lynch says about his early days, “huge worlds are in those two blocks.” Unsurprisingly, Lynch and his work has often compared to a twisted, acid-soaked Norman Rockwell: a nightmare twist on wholesome Americana. The comparison holds some ground, but Lynch is more like Edward Hopper, whose disconcerting portraits of small-town America in paintings like Summer Evening (1947) could easily be a scene from Blue Velvet or Twin Peaks. The paintings themselves don’t reveal dark underpinnings, but the undefined faces and ambiguous body language hints at a jaded view of American life rather than a celebratory one. The paintings tell a story but ask more questions than they answer, leaving the viewer with a sense of dread.

Lynch also drew heavily from surrealist painters like Max Ernst and Rene Magritte, who rendered the familiar unfamiliar. Surrealism is often wrongly interpreted as being “weird for the sake of weird” but most surrealist paintings use dream logic to disrupt and disturb institutional beliefs and systems. While filmmakers like Luis Bunuel used surreal imagery to dismantle the religion and the church, Max Ernst tackled the comfort and safety of the home with mixed-media works like Two Children are Threatened by a Nightingale (1924). For Lynch, the threat was always “inside the house” as violence is most often perpetrated by loved ones or neighbors rather than abstract boogeymen. The horror of the home, built up as an institution in America, is that the illusion of the idyllic nuclear family in the perfect home is used as a means to shame and conceal the violence that lies within.

Lynch himself would often unveil the hidden violence that lies beneath the veneer of neighborhoods, communities, and homes. Lynch’s mixed-media art, like Pete goes to his girlfriend’s house (2009), share similar themes and aesthetic considerations as Ernst’s work, focusing on the wooden construction of a home and the disjointed attack by an impossible outside force. Ernst picked nightingales, Lynch transforms the titular Pete into a murderous monster, building on his career through line which depicts domestic violence as, perhaps, the most palpable and horrifying threat against the American dream.

Environment plays a huge role in Lynch’s world view. His emotions and artistic visions shifted as he moved from Idaho to West Virginia and then from Philadelphia to California. This vision often contrasts between different worlds, how a small town could have endless universes colliding, while a large city is spiritually empty. Philadelphia especially shaped his early short films and his first feature, Eraserhead (1977). The eccentric behavior of neighbors and the struggle of raising his first child in a city bleeds into his art and films. This period marks the beginning of decay, and in his personal life, it seems like Lynch became obsessed with the rotting process of different organic materials, like keeping a collection of fruits and dead animals in his basement. It’s during this period he also visits a morgue and is able to see dead bodies, where he began to imagine disjointed and mundane narratives for the dead bodies he encountered for strangers he only met after their deaths.

Lynch’s vocal appreciation for artists like Lucien Freud and Francis Bacon make sense within this context. Like Hopper and Ernst, these painters often depict scenes that seem to be in the middle of happening. Narratively, they often tell a complicated and disturbing tale without filling in all the spaces for the viewer. There is a tension as to whether something terrible has just happened or is about to, an idea present in Lynch’s films. As much as he evokes the surrealist spirit of unveiling the concealed reality or rendering the familiar absurd, his storytelling often feels incomplete. He feeds you just enough to understand something terrible hangs at the edges of the frame, but the full extent of that nightmare never comes to light. For Deleuze, the most powerful image within Bacon’s work was the silent scream—a horrific and dystopian vision of terror that repeats itself time and time again within Lynch’s films like Blue Velvet, Twin Peaks, and Inland Empire.

In The Art Life, the idea of the artist as a genius is disrupted. Rather than portray Lynch as an eccentric mastermind, he’s presented as an outlier who worked incredibly hard. Lynch was lucky in many ways to have a supportive family and to work under the tutelage of American artist Bushnell Keeler at a young age. He offered Lynch studio space and pushed him to be diligent about his art. The book The Art Spirit by Robert Henri also shaped Lynch’s desire to live the life he imagined, which involved smoking, coffee, and painting. Lynch’s success was built in part by opportunity and support systems, but was fundamentally the product of hard work.

Film writers have become tangled in the “correct” way to approach the artist’s role in their work, but Lynch doesn’t make it easy. He often seems intangibly connected to his vision, his emotional interpretation of the world mapped onto the screen. His works exist in a kind of binary between still and moving image and also between painting and sculpture. Lynch’s symbols and coded allusions serve as a representation of our collective inability to face the dangers that lie within our homes and neighborhoods.

Watching Lynch work in his studio as an old man, he seems curious and flexible. He credits his father’s influence on his weekend plans, forcing him to take on different projects around the house and making them fun as an integral part of his desire to work in mixed media. Within the film, Lynch’s young daughter Lula often lingers around his work. She observes him, or paints alongside him. Parenthood suits him, in spite of what Eraserhead implies. At the heart of his disruptive art, this distrust in the home and family is perhaps the fear of his own inadequacies. The apt derision of the falsehood of the home acting not as a representation of his own flawed life, but the troubled one he saw around him. At the heart of projects like Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me was never a desire to see the world burn, but an empathetic consideration for the victim caught in a silent scream. Lynch’s apprehension about the illusion of small-town America lies more in the potential for love rather than the lack of it.