Note: This review was originally published during AFI Fest last year.

Anyone who criticizes Jafar Panahi for retreading themes in his work at this juncture of his career is kind of an asshole. The man is under the thumb of a dictatorship and forbidden from making movies. What else is he going to muse on with his films (which he continues to make despite the ban, because he’s great) besides muzzled creativity? With This is Not a Film, Panahi essentially used a documentary as a personal journal. In Closed Curtain, he and co-director Kambuzia Partovi transform his situation into a metaphorical (and metafictional) tale, one that picks itself apart as it goes along in order to lay bare Panahi’s persecution.

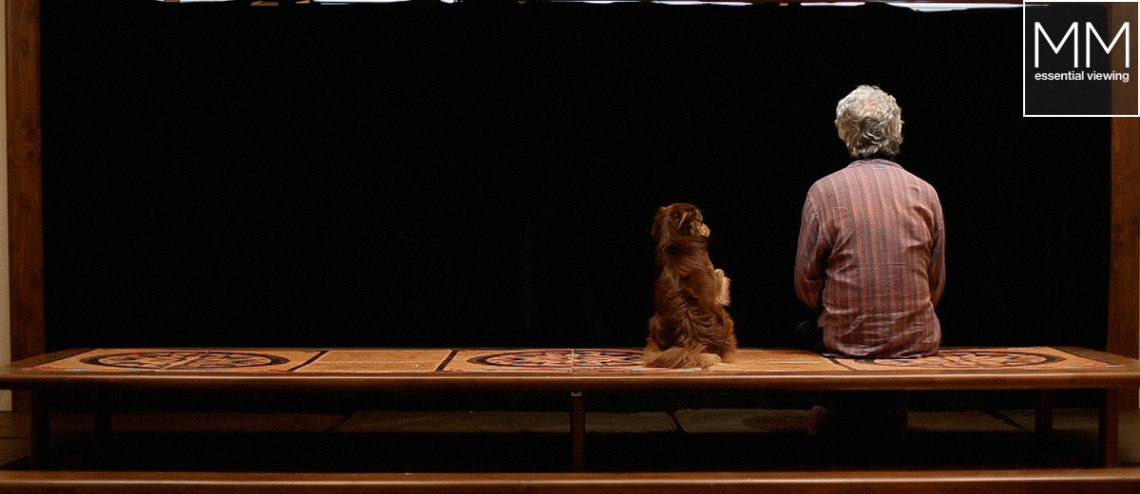

A writer (Partovi) secrets himself in a friend’s seaside villa so that he can work. He draws black curtains tight over every window so that no one will suspect that the house is occupied. He wants to make sure that his pet dog, Boy, is kept safe (dogs are banned from being in public in Iran). Eventually, the writer’s seclusion is disrupted by Melika (Maryam Moqadam), a woman who seeks refuge with him from the police. As time wears on, the two clash, with Melika wanting to tear down the curtains and stop living in fear of the outside, and the writer suspecting her of being more than what she claims. After a certain point, the movie goes into full-on surrealistic mode, as the characters show awareness of their fictional nature and begin to fight over both how the story will end and what it will mean.

Closed Curtain isn’t subtle. Even if the viewer is unaware of Panahi’s house arrest or even the political climate of Iran, it would be hard to miss the messages and symbolism here. The writer represents the creative spirit under oppression, while Melika is the impulse for freedom from oppression through self-destruction. She is described as having “a knack for suicide” and eventually advocates that option as the best, most honorable escape from the regime. For his part, the writer just wants to be left in peace with his beloved dog. Anyone allergic to thematic bluntness will probably chafe at this. But, while obvious, the movie is neither pretentious nor condescending. Rather, it’s being upfront. It’s starting the conversation before the audience has even left the theater.

The story of Closed Curtain feels very much like a dramatization of Panahi’s emotional turmoil during his arrest, as seen in This is Not a Film. That movie had him in a cramped apartment, his restraint acutely visualized. This allegorical interpretation plays out in a generous mini-manse, the broader spaces paradoxically showing how the mind is larger than one’s real environment. Both films are, by necessity, confined to their single location. Both even feature stupendous pets as the main characters’ sole companions. Panahi had his daughter’s lizard in This is Not a Film, while the writer has Boy. And Boy is the best cinematic dog since the double tap of Uggie and Cosmo in 2011. He’s adorable and brimming with personality, and a perfect symbol of the blameless things that are vilified by the Iranian regime.

Closed Curtain is harrowing in how it lays out psychological distress through artistic repression. It carries the same message as This is Not a Film, but delivers it in a different way, and with a more upbeat, hope-filled conclusion. Jafar Panahi can still find ways to make movies, and he’ll keep using them to rattle his cage for as long as it takes for the cage to be unlocked.