California has long had a reputation for fringe religions and occultism. Referring to the first three decades of the 20th century, Philip Jenkins says in his book, Mystics and Messiahs: Cults and New Religions in American History, “Religious entrepreneurs found in the West the means, motive, and opportunity to form new sects.” Among others, there was the Los Angeles-based Blackburn Cult, whose heyday in the 1920s predated the major cult scandals of the 1970s by half a century. Led by May Otis Blackburn, who claimed to receive directions from angels, the group was wrought with scandals, including a grand-larceny case and the murder of a 16-year-old girl. California, more than any Western state, attracted a combined migrant population of wellness seekers looking for miracles and young people searching for fame. These factors have contributed to California’s cultural perception as a hotbed of cult activity—and the movies have long reflected this.

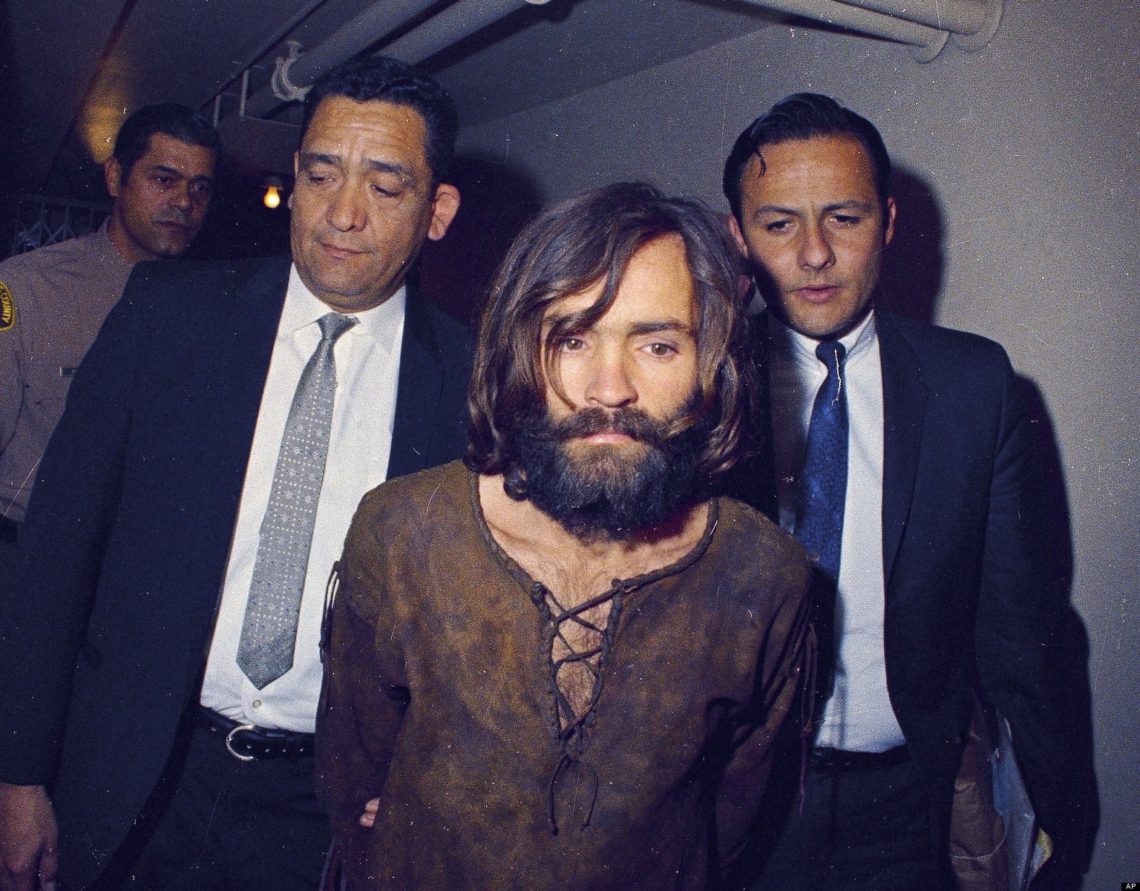

Charles W. Ferguson once said of America in The Confusion of Tongues, “It should be obvious to any man who is not one himself that the land is overrun with messiahs.” Along with abusive behaviors such as forced financial contributions, antisocial behaviors, and violence, Messiah figures like Charles Manson, Jim Jones, and David Koresh have long been woven into the national story of fringe religious misbehaviors. While religious fringe groups have existed since the first American pilgrims escaped persecution in the U.K., it is only in the late 1960s, thanks in large part to a hungry mass media, that cult fears took on a national resonance.

With the rise of the countercultural movement, which saw thousands of young people migrating West over the course of the 1960s, a growing mistrust of youth was spreading across the country. As a result, for many, the 1969 Tate-Labianca murders committed by the Manson family felt inevitable amid all the cult fervor. Joan Didion, in her essay “The White Album,” said of the news unfolding, “I remember all of the day’s misinformation very clearly, and I also remember this and I wish I did not: I remember that no one was surprised.”

Charles Manson and his followers became emblematic of a generational shift and a high-octane fear campaign against cults across the country. The Manson family murders became molded over time into a Hollywood narrative, serving as a map for future cult fears as the facts of the case were twisted and adapted to suit new anxieties. As a result, Charles Manson, still in prison today, has slowly been formed into a demigod as much by the anti-cult speakers as by his followers. As Karina Longworth put it on one episode of the podcast Longform, Charles Manson was a “loser”—so how did he become the embodiment of hell on earth?

Foreshadowed by Rosemary’s Baby in 1968, the 1970s saw a string of films that reflected growing anxieties in a post-Manson world, many of them zeroing in on the distrust of youth culture and the supposed rise of occultist beliefs along the California coast. One of the earliest such movies was The Mephisto Waltz (1971), which portrayed Hollywood as an immoral and supernatural hotbed of decadence and dangerous cult behavior. Paul Wendkos’s film explores the crumbling marriage of a California couple when their lives become entangled in an elitist occult group. Over the course of the film, an increasingly weary Jacqueline Bisset navigates occult-heavy sex parties, with point-of-view traveling shots equipped with a fish-eye lens emphasizing the horrors of these sequences. With these distorted faces and bodies, Wendkos and D.P. William W. Spencer visually tie the moral relativism of the upper class to bizarre supernatural rituals. God is dead, and in his place, beautiful and wealthy fame-hungry monsters have taken over.

The Mephisto Waltz is not a particularly great film largely due to weak subtext and non-existent character development, but it nonetheless zeroes in on what many people saw as unquestionable back then. The Manson murders and the rise of cults in the 1960s was a reflection of what many saw as the truth about the entertainment industry: Hollywood was at best morally corrupt, at worst complicit in the rise of violent cult behavior in the country.

For the most part, though, this anti-cult pattern was reflected more in documentaries and television than in narrative fiction, as fear-mongering masquerading as truth established itself as the popular media rhetoric. In 1973, Manson, a documentary that was just barely a notch above being an exploitation film, showcased the inner world of Charles Manson with exclusive footage of the family before and after the murders. With an ominous-voiced Vincent Bugliosi, the chief prosecutor for the Tate-Labianca murders, acting as a guide, Robert Hendrickson and Laurence Merrick’s film offers an almost apocalyptic version of events. Standing awkwardly and repeating rigidly rehearsed lines, Bugliosi says, “The establishment smugly dismisses the Mansons as an oddball phenomena. These kids come from our schools, our own neighborhoods, or own homes, by the time the Sadies and the Leslies they’d witnessed over 14,000 killings on television.”

This paranoid rhetoric would only grow and amplify with the Satanic Panic of the 1980s, which was founded on an almost entirely invented epidemic of Satanist cults living across the country and sacrificing babies. Charles Manson remained a central image of the inevitability of cult violence during this time and was even featured in the landmark NBC special, Devil Worship: Exposing Satan’s Underground, hosted by Geraldo Rivera, which an estimated of 10 million Americans tuned in to watch in 1988. Part mondo documentary and part roundtable interview, the show portrayed the rise of Satanic cults while offering precious little evidence. At the center of the film was an interview with Charles Manson which marked an important shift in Manson’s public image. While back in 1969 he had represented for many the demonization of the hippie movement, by the 1980s he had been transformed into a member of an extensive Satanic Network holding America hostage. Manson became indistinguishable from the targets of his murderous rampage, in many ways coming to represent Hollywood itself. The media, in a self-cannibalizing pattern, fed into the evangelical fear of the evils of the entertainment industry and created an almost pornographic culture of Satanic paranoia.

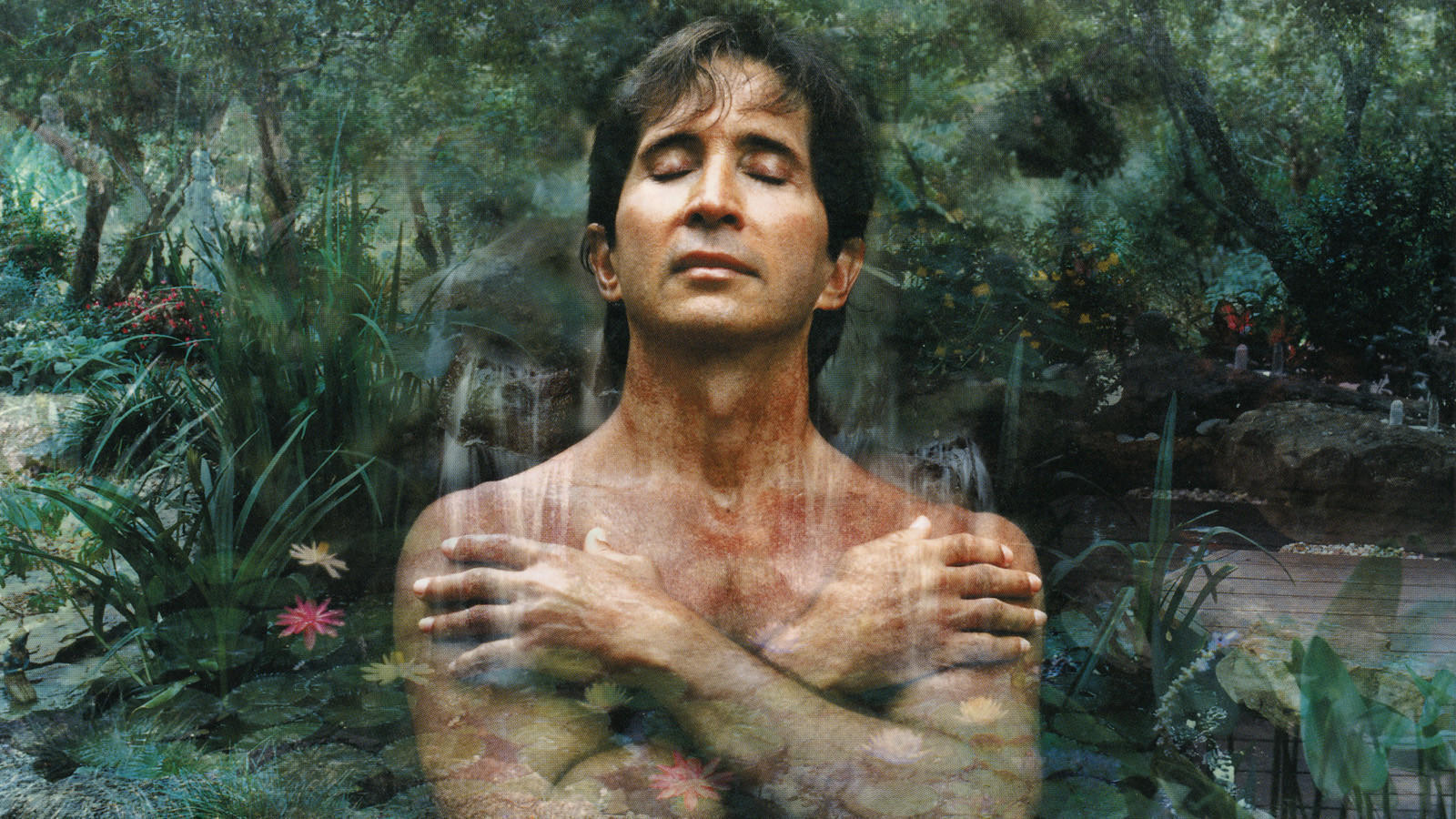

By the early 1990s, the Satanic Panic began to fade in the wake of damning FBI investigations and the exposing of many anti-cult speakers as fraudulent. In recent years, documentaries like The Source and Holy Hell have sought to tell the story of California cults from the inside, demonstrating that it was not a hotbed of evil and murder, but a path of enlightenment for alienated young people. While neither of the cults examined in these two films were prone to murder or suicide, according to most reputable sociologists studying cult behaviors in the United States, the idea of a murder-suicide cult has been gravely exaggerated. The truth is usually much simpler: that in the pursuit of happiness or health, fringe religions attract young or disaffected people searching for meaning. Like most organized groups of people, power and time wear away at idealism, and darkness eventually invades something founded on utopian principles.

Nevertheless, judging by some recent fiction films, there may still be life left in the idea of a Hollywood cult. Kevin Kolsch and Dennis Widmyer’s 2014 film Starry Eyes, toying with the blurred line between Hollywood and pornography, uses the idea of Satanic cults as a means of exploring Hollywood’s history of sexual exploitation. It suggests an inherent evil in the entertainment industry that’s like a black hole of immorality swallowing up the youth and innocence from women in search of fame. Cult portrayals such as these suggest that the devil is living off the American Pacific Coast and is being kept alive by a hungry elite.

Karyn Kusama’s thriller The Invitation, released earlier this year, zeroes in on a different and more commonplace elite. At a dinner party reuniting former friends and a man with his ex-wife, hints are strewn throughout that the hosting couple may be hiding something. It turns out that, two years earlier, Will (Logan Marshall-Green) and Eden’s (Tammy Blanchard) son died tragically, and it seems that Eden and her new husband, David (Michael Huisman), have joined a cult in order to cope with their grief.

Rather than focusing on a glassy-eyed cult influence, a supernatural impulse or violent carnage, The Invitation allows the audience to experience a more intimate horror: the dread and despair that might lead someone to abandon any natural relationship with death. Keeping the charismatic leader at bay, confined to brief snippets on a small laptop screen, the anxiety of the lies we tell ourselves rise to the surface. In particular, Tammy Blanchard plays Eden as a paragon of dead-eyed optimism that threatens to unfold at the edges, her quivering smile suggesting a tragedy she struggles to contain. Her suffering, as with those of the other members of her vague cult, overflows into the world, patterning themselves off murder-suicide pacts of the past.

Without hinting too obviously at any particular cult inspiration, The Invitation begs the question: Are we cycling back into old patterns? With a soundtrack that aches with pregnant silences and the soft roar of distant traffic and howling coyotes, Kusama’s film hints at Los Angeles’ quiet inner melancholy. How different does the night sound in 2016 Los Angeles than that night in 1969 when the Manson family brutally murdered Sharon Tate and her friends? Hollywood has helped set in stone a new modern mythology that shapes the values and desires of the American dream, but beneath the surface of the “dream factory” is a spiritual emptiness that Kusama reflects in her film.

Perhaps the ever-increasing scrutiny leveled at Hollywood’s unofficial fringe religion, Scientology—especially through two recent high-profile documentaries, Going Clear: Scientology and the Prison of Belief and My Scientology Movie—has led to this rediscovered fascination into the fringe beliefs of Hollywood elites. Combine that with an ever-growing wellness industry and the irresistible lure of the rich and famous, and it seems that California-bound cult cinema is here to stay.

One thought on “Drinking the Kool-Aid”

Pingback: Modern Family Starry Night Episodes Of Bones | Easy Watch tv