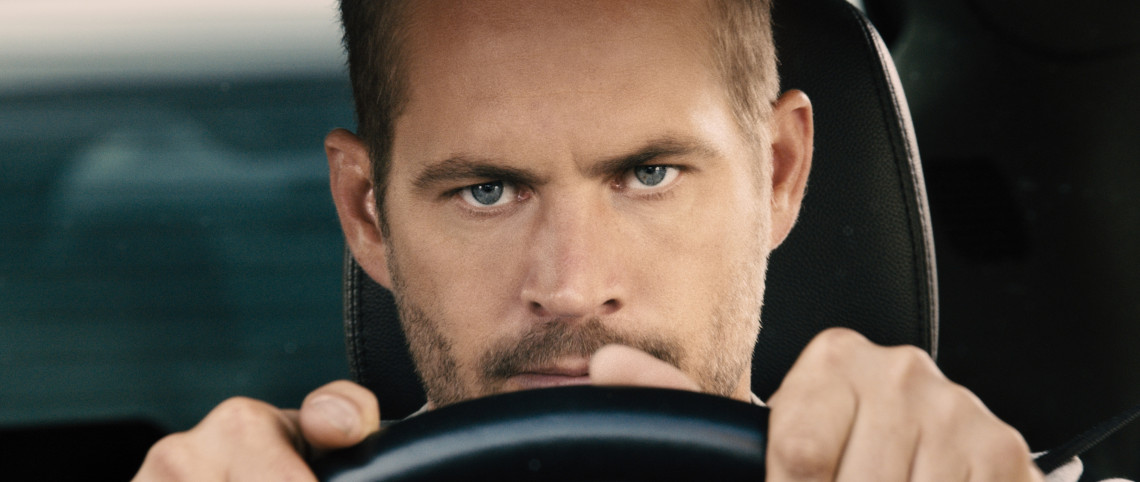

The death of Paul Walker during the filming of Furious Seven posed an unprecedented challenge to director James Wan and his crew. It was, of course, hardly the first time an actor had passed away while working on a film, but never before had it happened with a figure of such of importance—to a major studio franchise, at least—at such an inopportune moment on such a high-budget production. In an earlier time, this could have completely scuttled the film—an option the producers considered during a break taken immediately after Walker’s death in November 2013. But we live in an age in which computers can create just about anything we ask of them, and so they opted to use a complicated combination of existing footage, stand-ins, and digitally fabricated faces to insert a facsimile of Walker into the remaining scenes of Furious Seven.

The technical-minded have speculated that this could be the beginning of a new wave of purely digital performances. We’ve seen such characters before in live-action sci-fi and fantasy—Star Wars, The Lord of the Rings, Avatar, etc.—but they’ve never been humans. CGI has come a long way, but in that respect, it’s yet to escape the uncanny valley. Could the partially faked performance of Walker’s character Brian O’Conner herald a new paradigm? Many have awaited Furious Seven’s release partially out of morbid anticipation to see how well the effect would work—some, like Indiewire’s Sam Adams, with more consternation than others.

While all of Adams’s concerns are valid, flesh-and-blood actors can rest easy for now. The faux-Walker in Furious Seven works, but only in the sense that it’s just convincing enough not to ruin O’Conner’s arc in the story—and even then, its implementation is shaky. Unwittingly, the film serves as a teachable example of acting and character in cinema by demonstrating how crucial the presence of the former is to the latter. Some may scoff at the idea that popcorn flicks like this ever demand any serious acting, but replacing Walker with a digital double shows how even the supposedly least complicated performance requires talent.

Adams’s most prescient worry was that audiences would spend the film wondering when they were looking at the real Walker and when it was his double on screen. His fear, it turns out, is merited, at least in my own experience of the film; even the knowledge of the trickery in play is an agent of distraction. Should this kind of special effect become more commonplace and better implemented, such speculation may fade away, the same way audiences these days don’t wonder about other kinds of CGI effects too much. For now, though, it’s an unavoidable side effect of the route Wan and co. decided to take. Perhaps a viewer somehow unaware of the real-life context wouldn’t spot the fakery—not consciously, anyway. Subconsciously, though, they might sense that something was up with Brian.

How well the effect itself works depends on the kind of scene in which it appears. It’s most difficult to differentiate the fake and real Walkers during action sequences, but the effects work in those scenes is really no different from the digital-face replacements that have become standard on stunt doubles in action films. There’s no time to look for, or really think about, the CGI-compositing seams amidst the quick cutting and rapid camera movement of contemporary blockbuster filmmaking. In this milieu, the Walkerganger is right at home.

It’s in the slower scenes of drama or exposition that the illusion starts to waver under scrutiny. For the most part, a canny viewer can spot which of these scenes employ the Walkerganger. In certain group scenes, Brian is conspicuously uninvolved in the proceedings, standing off to the side and not saying anything. If he does say something, he’s either out of frame or not looking at the camera as he does so. Frequently, he’s seen from far away; for close-ups, however, he’s either partially obscured by shadow, not completely facing the audience, or some combination of both. Throughout cinema history, the editing and photography of performance has evolved its entire visual language around emphasizing physicality, vocal delivery, and especially facial expression. Deliberately avoiding these conventions to cover the shortcomings of a digital effect means that while Brian is physically present throughout all of Furious Seven, his character seems emotionally distant from the action. He’s inhibited from substantial interaction with the people who are supposed to be his closest friends and family.

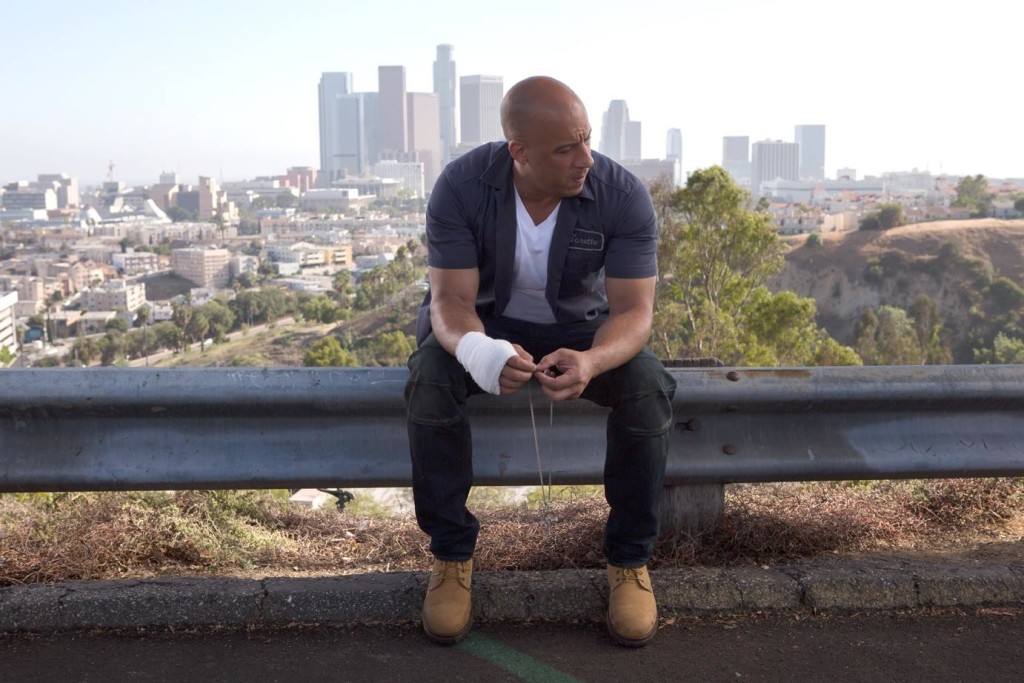

But the movie doesn’t always have the Walkerganger at the margins in non-action parts. Much was made of how the story was rejiggered to accommodate Walker’s departure, writing Brian out of the series by giving him a happy retirement instead of killing him off. To this end, several scenes were shot for a new subplot in which Brian struggles between his duty to his growing family and their safety, and his desire for action. Many of these scenes have other characters, usually Dom (Vin Diesel) and Mia (Jordana Brewster), talking about said struggle. Even the scenes that do feature Brian have the other characters talk at him, not with him, most notably one that takes place between him and Dom during a quiet moment on a plane.

But the movie doesn’t always have the Walkerganger at the margins in non-action parts. Much was made of how the story was rejiggered to accommodate Walker’s departure, writing Brian out of the series by giving him a happy retirement instead of killing him off. To this end, several scenes were shot for a new subplot in which Brian struggles between his duty to his growing family and their safety, and his desire for action. Many of these scenes have other characters, usually Dom (Vin Diesel) and Mia (Jordana Brewster), talking about said struggle. Even the scenes that do feature Brian have the other characters talk at him, not with him, most notably one that takes place between him and Dom during a quiet moment on a plane.

This fulfills the needed narrative function, but only in the most perfunctory way. It’s dispiritingly disengaging to see someone’s internal struggle play out in other people’s dialogue. There’s a reason the only truly convincing part of this subplot is one that featured the real Walker: the scene near the beginning in which Brian drops off his kid at school, which starts out looking like he’s preparing for another street race, but then reveals he’s just anxious while waiting in a queue of minivans. The way it conveys his conflicted mindset towards his new life is cinematic storytelling at its most basic, but it works, and that sense of showing and not telling is what the bits that are about Brian but don’t feature him are missing.

This is not necessarily the result of any ineptitude on the part of the filmmakers, who did the best they could with the material they had. It’s easy to see why they worked around the Walkerganger as much as they could whenever it gets put on full display: The effect just isn’t convincing. More than that, the homunculus of Walker is unintentionally creepy, especially when it smiles. The voice is also off, the constructed dialogue usually coming through an odd syntax in a flat tone.

I say none of this to decry Furious Seven or the people who made it, because they may have had no other choice. The only other real option would have been to rewrite and reshoot large swaths of the film so that it simply no longer included Walker, which not only would have been financially ruinous but also hugely disappointing for fans of the series and that character. But anyone worried that digital actors now have any kind of leg up on real ones needn’t be—not right now, at least. At the rate technology keeps improving, we’ll probably see photorealistic CGI people sooner or later. But for now, it turns out we still need humans to bring humanity to live-action movies.

2 thoughts on “Bringing Humanity to the Screen: Paul Walker & “Furious Seven””

Brilliant article, Dan. I haven’t seen F7 yet (looking forward to it, though) but I held grave fears when the studio said they were pressing ahead with the “digital face replacement” option, largely because of what you mentioned; the uncanny valley effect.

From what I’ve been hearing, however, this isn’t as big a problem for the film as I originally feared. I, for one, am glad Walker’s character was afforded the opportunity to go out gracefully, rather than a line of dialogue from a supporting character and he’s “off screen” without a second thought.

Pingback: In Review: 4/6 - 4/12