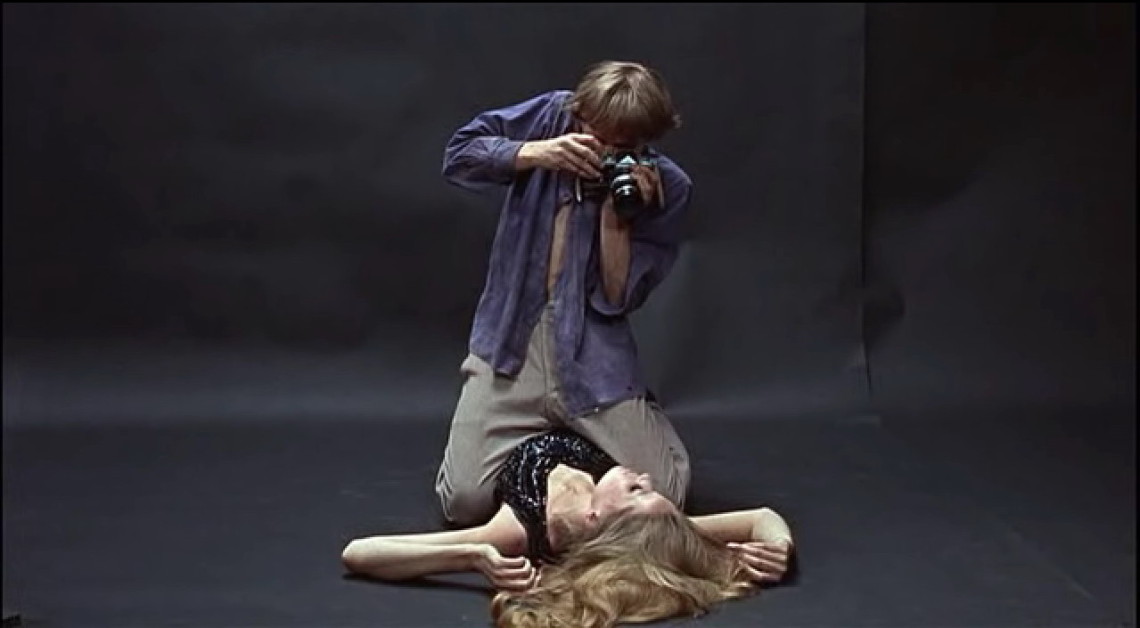

Compared to L’Avventura (1960) and L’Eclisse (1962), Blow-Up isn’t one of Michelangelo Antonioni’s most-loved films in critical circles, and arguably hasn’t been as extensively covered in scholarly study and critical analysis over the decades. Moreover, the appropriation of Blow-Up as an emblem of 1960s London in all its swinging glory and creativity certainly doesn’t help its critical standing, reducing it to the more vulgar status of a cult film. The iconic poster, showing David Hemmings’ photographer Thomas straddling model Verushka from above as she lies on the ground is a staple of many a hip university dorm.

Yet upon watching the film, dissociating it from its acquired significance, it quickly becomes obvious that Blow-Up is far more complex than it may seem, or at least has been understood to be. Its dealings with pop culture do not preclude it from depth and worth. In fact, at the end of a year in which politics, personal ethics and entertainment have collided in increasingly disturbing ways, Antonioni’s study on life, death, art and meaninglessness feels more relevant than ever.

In its early moments, Blow-Up looks and feels like a bad imitation of an Antonioni movie. The film opens on a crowd of elderly people seen leaving a flophouse in total silence. Later, we see brutalist social housing in construction, beautiful cars, an antique shop, and even a troupe of traveling mimes who instantly recall those in Federico Fellini’s Nights of Cabiria (1957). As such, the film seems to tick all the boxes of what an Antonioni film is sometimes reductively thought to be. Yet here the director does not pick up on any of the latent ideas usually associated with such imagery: respectively, poverty, modernity, time and decay, and the absurdity of living.

The profound existential dread so vividly felt in L’Eclisse when Monica Vitti’s Vittoria walks around a quiet town or visits the chaotic stock market is totally absent here despite the presence of similarly symbolic imagery. Here, images instead all seem benign, hollow even. This time, a building is just a building. Hasty, nonchalant, almost inattentive direction replaces the careful camera movements and meticulous framings of Antonioni’s previous films, a style which made elements transcend the screen and feel like real, three-dimensional objects. Buildings which in L’Avventura stood tall and menacing and so coldly indifferent, here only seem boring, even a little silly in their strange architecture.

This is because Blow-Up does not align with the perspective of a person in the throes of an existential crisis, but rather with that of a man whose sole concern in life is photography. Largely based on David Bailey, who photographed icons of the swinging 1960s from the Rolling Stones to the Beatles and Andy Warhol, Thomas is a young, successful artist who greets everything and everyone he encounters with amusement and mild mockery.

It isn’t so much that Thomas is selfish, but that feelings have no place in his entirely anesthetized world. The abundant surfaces around him never refer to anything other than themselves. In this world, images are completely divorced from meaning. A photo shoot looks like sexual intercourse but isn’t, a woman loves a man but sleeps with another, a propeller becomes an art object, Paris is mistaken for London, and so on. Meanwhile, the symbolic elements typical of Antonioni’s films here feel like cliches, prepackaged ideas that seem absurd and ridiculous in this world of insignificance (tellingly, “cliche” means “photograph” in French).

During one of his customary meandering journeys across London, Thomas winds up in a park and photographs a couple there. When the woman (Vanessa Redgrave) catches him in the act and immediately asks to retrieve the pictures, Thomas of course mocks her concern for privacy. “It’s not my fault if there’s no peace,” he says, and one wonders what Thomas—or Antonioni, for that matter—would think of our contemporary world, a time in which our lives have never been more public, whether we wish them to be or not.

After Thomas and the woman engage in a peculiar sequence of mutual attraction and seduction in his studio, he naturally gives her the wrong roll of film and proceeds to develop and examine the pictures which caused her such anxiety. One of the most striking and beautiful images he develops is of the woman looking towards the camera, her face forever frozen in an expression of terror harshly accentuated by the picture’s black-and-white palette. In another image, she seems to be looking at something over to her left. Thomas swiftly sets out to find out what this object is with a series of close-ups on sections of the image. In this sequence of investigation—edited and scored with unsettling stops and starts—Thomas’ curiosity leads him to finally reach beyond the realm of the beautiful to look for a meaning behind the image.

Put together in a way that touchingly recalls Chris Marker’s masterpiece La Jetée (1962), the photographer’s grainy enlargements reveal a man with a gun hiding in the bushes and the immobile body of the woman’s lover lying in the grass. But it is not until he goes back to the park and sees the body still lying there that Thomas appreciates the extent of what he’s inadvertently witnessed. In his usual arrogance, he naively thought he had saved a life back there, that his interruption had heroically prevented a man’s murder.

It is only when faced with the dead man’s body that Thomas is finally forced to face his own arrogance and illusion of control, qualities which more or less defined him up until this point. As it turns out, there is something at stake after all. It is at this point that death suddenly engulfs the film, crashing on Thomas like an unsuspecting wave and pushing his whole life out of balance. It taints every single image, restoring to previously banal elements their cruel indifference. Thomas, who has rather symbolically forgot to bring his camera back to the park, cannot reduce the dead body to a harmless image anymore.

The specter of death and the lack of control becomes even more acute when Thomas finds that someone has stolen from his apartment all pictures but one, an ominous close-up of the dead body. Scared and unsettled, he drives into town and glimpses the mysterious woman again. The sequence in which he follows her through a crowded club where the Yardbirds are playing (a young Jimmy Page from Led Zeppelin fame can be seen on guitar) is one of those seemingly commonplace scenes that now, in the context of death, responsibility and danger, reeks of indifference, emptiness and selfishness. An angry Jeff Beck smashes his guitar and throws its neck into the crowd. Thomas catches it and fans fight to get this worthless piece of wood from him. This sequence is more than a metaphor for herd mentality, but an authentic example of it, which only makes it much scarier.

That Thomas eventually throws the guitar neck away is a small, bitter victory for his newfound set of priorities over mass illusion. He only rids himself of the object once he is standing outside of the context in which it is valued. It is realistic and poignant how incomplete Thomas’ reckoning is. Confused, he does not understand exactly what it is that has changed inside him. There is no close-up on his face looking at the guitar neck he’s holding with an air of bewilderment. Rather, this is all to be understood by the active viewer.

Indeed, Blow-Up as a whole plays like an enigma for us to resolve. Earlier, there’s a sequence in which Thomas’ friend Bill, a painter, explains that his art is pure chaos until he finds a structure in it; only then does he know what his piece is about, the work emerging “like a detective story.” This moment is crucial as it clearly indicates to the viewer that the chaos of the film’s early moments will eventually find its structuring principle: namely, apathy.

From the moment Thomas sees the dead body in the park and starts paying real attention to all the things around him, Antonioni’s direction becomes more focused and precise. As Thomas loses sight of the mysterious woman in the chaos of the gig, he decides to go to a house party and find his agent Ron (Peter Bowles) to explain to him what he has seen. The man is simply too high on drugs to hear him. This detail echoes the earlier scene in which Thomas and the woman smoked some grass in his studio until she felt guilty for ignoring the real life-and-death reason why she’d come to visit him. Thomas now feels the same helplessness and urgency she felt as he tries and fails to convey the importance of what he has to say.

What is so bleak about this situation is that the people at the party do not consciously ignore Thomas, but that they have plainly and simply lost the ability to care. Responsibility towards one another isn’t possible in this configuration of society. Disheartened by his friend’s indifference, Thomas reluctantly and heartbreakingly concedes to staying and partying.

Returning the next day to the park, Thomas finds that the body has disappeared, and with no one aware of the man’s death, it feels to him as though the victim had never existed at all. Thomas’ attempts to do justice to this man and his existence, to make sure his death won’t go unpunished, have failed. For the first time, the photographer is faced with the triviality of a life in this society where notions of basic humanity have all but disappeared.

So what is there left? What is life in a world like this? The answer comes from the same group of mimes Thomas encountered at the beginning of the film. This time, they appear playing tennis in the park with an invisible ball. The photographer smiles sadly at their dedication to the fake game, but when they silently ask him to retrieve the ball and throw it back into the court, he does so just to please them. Yet in the following close-up, his face turned up to the sky as if in supplication, we see Thomas’ eyes gradually come to follow the ball as it lands. His pupils move from right to left and for the first time we can actually hear the non-existent ball being played.

While Thomas’ encounter with death awakens him from existential slumber and forces him to perceive reality for the first time, he realizes just as quickly that this knowledge is pointless if no one else shares it. Thomas knows that people believe in an illusion in the same way that the mimes believe they are playing tennis. But in the film’s closing moments, when Thomas decides to perceive the ball, he finally understands that he has no choice but to drink the Koo-Aid, take the blue pill and return to that illusion in order to survive. His literal fading away at the end of the film captures the intensely sad moment of his surrender.

Blow-Up is one of Antonioni’s most accessible films, but also one of his most ferocious. Its utterly hopeless cry at post-war indifference is all the more powerful because the film takes the time to establish and “normalize” the postmodern society of the 1960s. The sudden, unexpected and overwhelming surge of emotion felt halfway through is perhaps even more gut-wrenching today at a time in which our society has become even more impersonal, our indifference all the more banal. Here’s hoping that in 2017, unlike Thomas, we won’t have to stand alone.

2 thoughts on “The Disturbing Relevance of “Blow-Up””

Thank you for such a wonderful write-up of a film that has intrigued and mystified me since a college Humanities class assignment over twenty years ago. I didn’t know what the heck was going on and how it all fit together but I knew there was a lot of something going on below the surface. My professor who assigned the movie was more about letting us figure out art for ourselves but everything in this piece helped all the images fall in place for me and a greater appreciation for the film itself.

Brilliant article. Most reviews that I have read on this film tell us about how the photographer was just imagining the murder; that his life seemed so boring that he had to find meaning in the ‘blow-up’ of a photograph to get an adventure started; that all this was in Thomas’ head and we can’t really know the truth. But your article makes more sense and has much more to say. And you have enough evidence from the movie to prove your point.

And I agree, it’s scarily relevant in 2017, a time when we are increasingly living in our own bubbles. Adam Curtis put it this way in his documentary ‘Hypernormalisation’: “You are so part of a system that you can’t see beyond it.”

“Here’s hoping that in 2017, unlike Thomas, we won’t have to stand alone.”

Sadly, 2017 seems even worse than the Swinging Sixties. Here’s to 2018….