Amanda Rose Wilder’s first feature, Approaching the Elephant, is set in the first year of the Teddy McArdle Free School in New Jersey. It’s wall-to-wall footage, no narration, all black and white. But it’s not really about alternative education. Instead, the documentary winds up approaching giant societal issues—how we live together, how we process our emotions and thoughts, how we decide on political directions—by letting us watch a year of interactions in the school. Wilder focuses on two children, Giovanni and Lucy, as well as the school’s founder and head teacher, Alex.

Wilder worked with editor Robert Greene (Actress, Listen Up Philip) on the film, which premiered at True/False in 2014 and has played at a number of festivals and screenings since then, including BAM CinemaFest. It will run at the Independent Film Project in Brooklyn February 20-26 as part of their “Screen Forward” series.

Wilder met me in Brooklyn in early February to talk about shooting the film, how her interest in poetry influenced the project, editing with Greene, alternative schooling, and the ways an individual interpretation of events can engage audiences in meaning-making.

In some of your interviews, you mention your college thesis on the poetic documentary and the documentary poem—so let’s back up. How did you get started with poetry?

It’s funny: a lot of my interest in poetry and in free schools came from my dad. My dad is a poet, and he’s also an elementary school teacher and he’s taught in a variety of different schools. He has a poetic sensibility to everything he does. When I was growing up in New Jersey, he would take me on nature walks and so on. So I feel like I developed some real sensitivity to the world in general, and an interest in poetry. I wrote poetry in high school, and then I went to Marlboro College in Vermont. That’s where I got into documentary.

I took time off from Marlboro because I wasn’t sure what I wanted my thesis to be on, which at Marlboro is a 2-year process. It’s more like a grad program, where you work one-on-one with one sponsor or two sponsors and a plan you design. So I ended up moving to Chicago with my boyfriend at the time, and I ended up working at a café. And in that café, I finally put together the idea of poetry and documentary. I went home and Googled poetic documentary.

What links them?

I’d just seen Gimme Shelter by the Maysles for the first time. I remember being in that room and standing behind the couch and thinking, “This is why I want to make documentaries.” Then I rewound it and watched it straight through again. What I like about those docs is that it’s a lot like a poem in that what it’s about is endlessly list-able. Gimme Shelter is about is the 60s, and the Rolling Stones, and the crowd. You could watch that movie 30 times and get something new out of it.

In that way, it’s a lot like a poem in that it is through a subjective eye of one particular cameraperson, then one particular editor. There’s a lot riding on those two people and their vision, yet it’s sort of this strange balance of subjective “I” who is viewing the world in an open manner and explaining it to people in a personal way, but also not articulating every little detail of a world in a way that makes it so fun.

Being hyper-observational about the world, and then reinterpreting and shaping that into something that’s personal, but in which other people can find other interpretations.

Showing the world through your eyes, but being very open to the world. Allowing people to have experiences in the world that they wouldn’t necessarily have—like being in a free school—but not passing too much judgment on it, so that you can, even in one shot, get so many things out of it.

There’s a scene in the film where there’s a sign in the clubhouse that says CLUBHOOSE RULERS, with “clubhouse” spelled wrong. In the scene, almost everyone in the school is together, building peacefully. In that one shot, you could say, “Oh, they spelled ‘clubhouse’ wrong.” You could pass some sort of judgment on that. If you were a free school person, you would have no issue with that, because free school people feel as if kids should learn to read and write whenever they want. But for someone who believes kids should read at a certain time, it would be an issue. Or you can also say, “Oh, wow, these kids have sort of become a family.” It’s almost like a prism, where you pick one point and then reflects different things.

So did the Marlboro experience get you interested in free schooling?

Yeah, I feel like Marlboro is where I learned the beauty of self-directed learning, because I really had to go to sponsors and say, “This is what I want to work on today. This is what I want to talk about.” My Dad took me to visit Summerhill, which is the longest-running free school, when I was in fifth grade. He was always a progressively-minded teacher, but he never taught at a free school. Then my film professor at Marlboro, Jay Craven, said, “I want to make a movie with you…about progressive education in some way.” So it actually was his idea. I agreed that it would be a good idea.

I went to this alternative education conference the summer after I graduated from Marlboro, and that’s where I met Alex [Khost, the founder of the Teddy McArdle Free School]. I did, like, 20 interviews, and would just grab people [at the conference] . . . Alex was really charming, and he had nice teeth, and was really comfortable in front of the camera.

How did Alex get interested in free schooling?

He had a really hard time in school—he went to public schools in suburban New Jersey—and was bullied, and didn’t really study anything he wanted to study, and just had a pretty horrible experience. And then his dad gave him A.S. Neill’s book Summerhill when he was 16, and it kind of changed his ideas about a school experience. At the time of the conference, he was living in suburban New Jersey. He had moved back and had just had a kid, and thought, “Well, I don’t want my kid to go to the kind of schools I did.” So that’s why he started McArdle.

In his first year at the free school, Alex wasn’t new to teaching, but he’d never taught in a free school, or in that age group. And it was for almost everyone at the school—except for the only paid teacher at the school, Dana, free schooling was a totally new idea. I think you get this if you watch the film: it is a free school in its first year.

Do you think alternative schools tend to attract both super-bright kids and kids who would be all over the place in the traditional classroom setting?

I think it does probably attract the kids like Lucy who have been doing something similar for a while, and then at the other end of the spectrum, the kids like Giovanni. That’s what’s hard about a start-up; they do tend to attract 7- to 10-year-old hyperactive boys who just can’t sit in seats all day. That’s not’s necessarily a criticism of them—they just need to learn in different ways. They need to be hammering—not necessarily fighting with the hammers [chuckles]. But that can be a problem for the school, because you end up with a lot of this sort of kid and it can make things difficult. I was reading The New Summerhill, and the author was saying that they always have a struggle with that one kid who’s tormenting 10 other kids. Do you keep them? Because if not, then where do they go?

Because they’re out of options.

Right. Then again, people say, “Oh, the movie seemed so chaotic, and there’s so much fighting.” You wouldn’t necessarily want that much fighting. But I also don’t think fighting is necessarily bad for kids. You’re seeing kids trying to negotiate conflicts themselves, which in a conventional school would be stomped out quickly by an adult figure. And is that any better? It might look calmer, but that’s because you have these authoritative figures making sure it is.

To me, it kind of felt like a family dynamic.

People also take the narrative totally opposite, saying that it dissolves into chaos. And then some people think that it gets better. I think I agree with the latter. The movie gets more intense. As a school, they really came together. It’s pretty incredible that at age 7, Ethan is able to propose that one of his friends not be at the school anymore.

They’re kids, and the thing about children is that they process things differently than adults.

I feel like the movie is really about the individual, certain individuals, and not really about free schools. Some people misinterpret it as being “about free schools,” and it is, but that’s more of the context or the framework. One of my main goals was to show how complicated even a kid is, even at age 7. The free school model is really about the need to capture that.

Did it seem like the kids were performing at times?

It was strange, because it was 8 years ago, and kids today are so much more media savvy. I do remember a kid saying now and then, “Oh, it’s gonna be on YouTube.” But in general, I feel like because I was there literally the first day of the school, when kids walked in, I was there. I think that helped them accept me as part of what was here. So much was just going on—if they were engaged in what they were doing, then they just forget you’re there.

Were they told to ignore you?

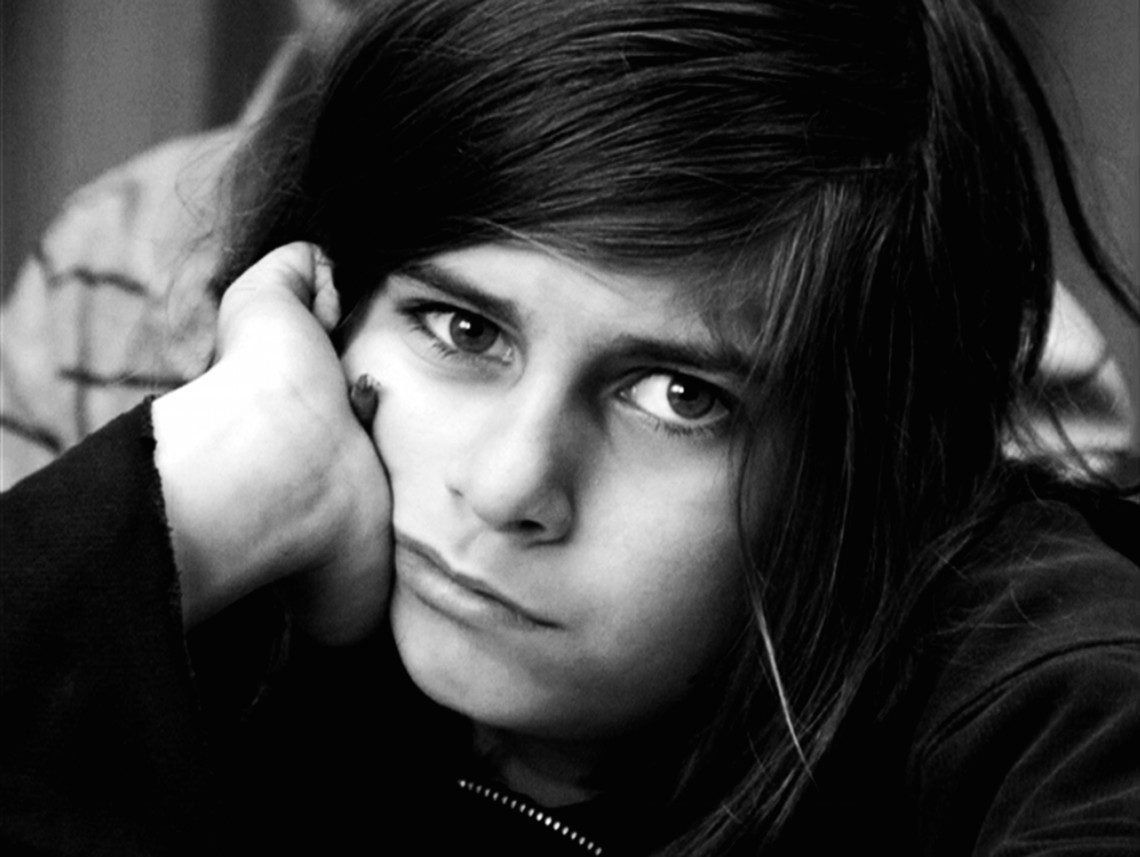

Yeah. In general, kids are less self-conscious in front of the camera than adults. But there were some kids who would say, “Stop filming me”—and I would—but luckily, those weren’t the people I was mainly focused on. The first shot you see of Lucy in the movie, where she walks in the door the first time, was literally the first time I saw her. I was captivated immediately by this person. She likes to work out things that she’s thinking about vocally, out loud, so maybe the camera allowed her to do that in front of another audience member.

Alex was very comfortable, too. I remember when Giovanni was expelled, he came up to me after, and it was the one time he said that he wasn’t sure I should be filming. And I was, like, “Oh, why?” Because to me, I was so happy to get that. I mean, I was crying. It was very sad. But from the first day of the school, I felt like Giovanni was going to be a challenge in some way, and that was the culmination of that, so I was happy to get it. But Alex said, “Well, it’s someone’s life”—and I understood that.

Then again, I was Giovanni at my school, and I had a very opposite experience. I was caught drunk once, and was given no second chance. My school had a one-strike policy, and I was very much ripped from the room. Giovanni was given 9 months of chances. He knew, and he knew everyone cared about him.

One thought on “Interview with Amanda Rose Wilder of “Approaching the Elephant””

Pingback: For Movie Mezzanine, Amanda Rose Wilder talks to Alissa Wilkinson. | Approaching the Elephant