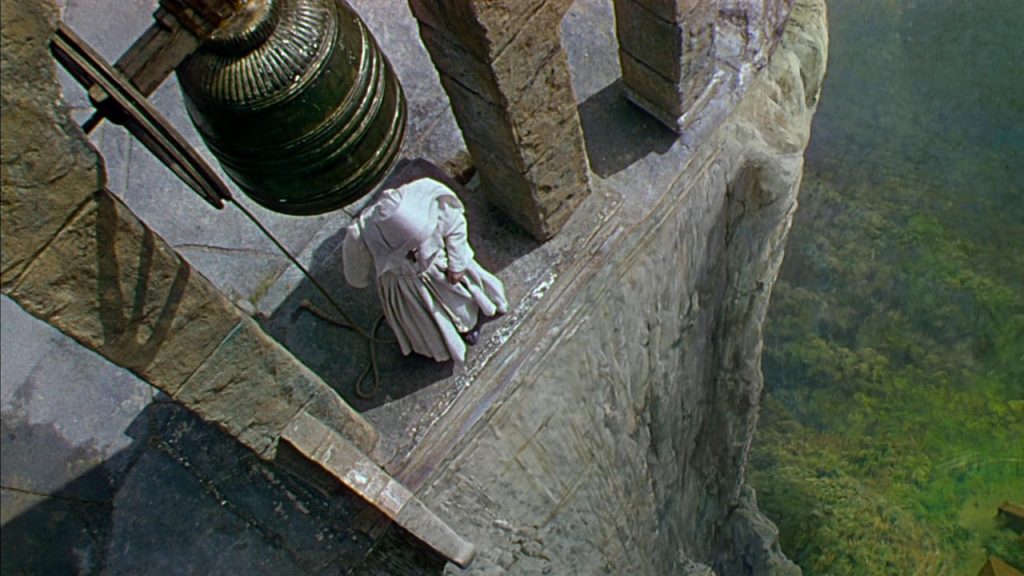

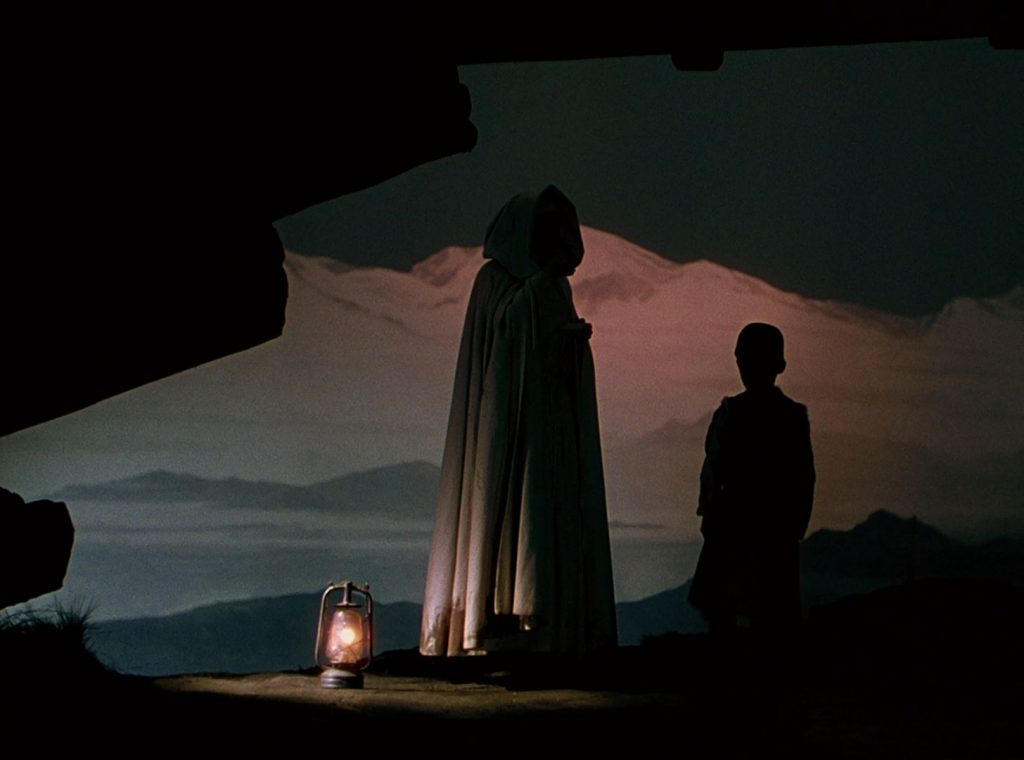

May 24 marked the 103rd birthday of the late Peter Ellenshaw, whose name you may not know but whose work you’re almost certainly familiar with. Ellenshaw started out in the United Kingdom as an assistant matte artist on three of the greatest British films of all time: A Matter of Life and Death (1946), Black Narcissus (1947), and The Red Shoes (1948), all of which are also from the greatest British filmmakers of all time, Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, also known as The Archers. But soon after, Ellenshaw jumped to the other side of the pond to work for the Walt Disney Company, as a matte artist on live-action classics such as 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954), Old Yeller (1957), and the quintessential Mary Poppins (1964). Peter Ellenshaw’s work extended all the way to Warren Beatty’s bright and colorful comic-book film Dick Tracy; three years after that film opened in 1990, Ellenshaw was inducted as a Disney Legend, the same year that the man who provided the original voice of Donald Duck was honored. Peter Ellenshaw, quite simply, was a genius. Here’s some proof.

As coincidence would have it, May 24 was the same day that I attended a press screening of Walt Disney Pictures’ latest live-action, special-effects-heavy extravaganza, Alice Through the Looking Glass. This sequel to the 2010 Tim Burton film retains many of the same elements: Johnny Depp, Anne Hathaway, Helena Bonham Carter, Mia Wasikowska, Stephen Fry, and even the late Alan Rickman return among the cast, although Burton himself didn’t direct this one. The most unfortunate element that this new, James Bobin-helmed picture retains is its visual style. Burton’s Alice in Wonderland was a 3D nightmare, an utterly garish, unappealing, and distinctively gross-looking movie, from its hideous take on Tweedledee and Tweedledum to the jaw-dropping and embarrassing CG-laden moment when Depp’s Mad Hatter does a dance called the Futterwacken. (Watch that video, but do so close to an eye-wash station so you can properly de-louse yourself.) Here’s further proof of that film’s horrendous design.

As a fan of Bobin’s two movies starring the Muppets, as well as someone who enjoyed his work on the HBO series “Flight of the Conchords,” I had (admittedly meager) hopes that Alice Through the Looking Glass might turn things around. Considering how the first film bastardizes both of Lewis Carroll’s novels featuring Alice, I wasn’t expecting anything remotely close to a faithful adaptation of Through the Looking Glass. I was hoping that Bobin would inject some personality into the film, some life, where none was present in the original. The good news is as follows (and constitutes a spoiler alert in case you’re seriously concerned about having the film ruined): there is no Futterwacken in Alice Through the Looking Glass. Thus, this film is an improvement on its predecessor. That is the end of the good news. The bad news, as evidenced by the trailers and borne out by the full film, is that Bobin and company instead operate under the assumption that if the first movie wasn’t broke, the second one shouldn’t fix it. The visual aesthetic and special effects haven’t gone away. If anything, they’re doubled down. See for yourself.

There are many, many, many reasons why Alice Through the Looking Glass is genuinely awful: the story is almost nonexistent and relies heavily on the audience trying to have sympathy for the two most obnoxious characters from the original film, both of whom just feel sad and stuff; the performances range from the actively creepy (hello, Johnny Depp) to the desperately-trying-not-to-phone-it-in-but-phoning-it-in-anyway (hello, Anne Hathaway); the time-travel elements introduced here as well as the new character Time, played by a Bavarian-sounding Sacha Baron Cohen, are so weakly built into the story that they shouldn’t even exist; and so on. Watching the new film in 3D, though, suggests anew that we need to revive the art of matte paintings, in the style of Peter Ellenshaw. This film, like its predecessor, suffers greatly because it’s painfully obvious that the human actors are walking next to or standing in front of green-screens for just about every scene that doesn’t take place in the real world. (It wouldn’t be surprising if some of those real-world scenes took place in front of green screens, too.)

You could argue–not entirely inaccurately–that the use of CG environments in modern live-action Disney films is the digital version of Ellenshaw’s analog paintings. When Mary Poppins floats down from the sooty skies of London, she’s doing so in front of Ellenshaw’s matte paintings, an old-school version of green-screen technology. When Kirk Douglas faces off against the squid on the top of the Nautilus, he’s doing so on a set placed in front of what would end up as matte paintings. The list goes on, whether it’s in the mountain-climbing drama Third Man on the Mountain or the Western-set weepie Old Yeller. Disney is no stranger to creating facades as the backdrops for decades of memorable stories set in live-action, not animation.

However, the effect of utilizing computer-generated imagery to suggest a fantastical world populated by all sorts of strange beings, at least in the Alice in Wonderland franchise, is the exact opposite of the matte paintings of old. Whether in a psychosexual drama set in a remote Indian village or in a coming-of-age tale of a boy and his dog, Ellenshaw’s art puts you in the middle of the story, to the point where it’s genuinely shocking to realize that Old Yeller wasn’t shot entirely in the desolate lands of Texas or that Black Narcissus wasn’t filmed in India, and so on. Ellenshaw’s matte paintings are immersive, the way that 3D technology was meant to be immersive after the massive popularity of James Cameron’s Avatar in 2009. Alice in Wonderland was the first big 3D release after Avatar, and it was about as non-immersive as possible. Alice Through the Looking Glass follows in that film’s footsteps, even managing to sidestep the relatively impressive, and no less omnipresent, CG effects work in Disney’s live-action Jungle Book from earlier in the spring.

There are, of course, a handful of human actors playing (primarily) human characters in Alice Through the Looking Glass, with Wasikowska as the most relatively normal-looking of the bunch. (Carter’s embiggened head and Depp’s bulging eyes are effects-aided, clearly.) But even in the simplest of moments or movements, Wasikowska appears to be walking through a 90s-era PC game, something akin to Myst. It’s not just that we, as audience members, inherently know that the Cheshire Cat or the White Rabbit or Tweedledee and Tweedledum aren’t real, that there’s special-effects trickery afoot. It’s that the filmmakers have absolutely no interest in convincing you otherwise. For all of the money spent on the visuals, there wasn’t a single cent spared here to work on special effects that feel special instead of perfunctory and lazy.

To be fair, Alice Through the Looking Glass would not be a movie worth seeking out if its visuals were peerless or among the top of recent films. It’s also worth noting that the film is far from the only movie that suffers from special effects that call attention to themselves for no good reason. The Jungle Book’s effects aren’t perfect, to be sure, but you get the sense that Jon Favreau tried very hard to make sure they appear seamless. Not so for Alice 2 and so many others of its ilk. This film’s script is as lifeless as the visuals, or nakedly fiscal in nature, as when Alice extols the virtues of China, which just so happens to be the location of a brand-new Disney theme park. (What a crazy coincidence!) But Alice Through the Looking Glass is still a Disney film; we’re 50 years and more from the release of the studio’s early live-action films, which attempted to create worlds you could touch in ways that didn’t rely on cheap gimmickry like 3D, even in an era when 3D was very much a popular fad. Not all of Disney’s early live-action films are great, but they all look remarkable, all the more so now that matte painting from a genius like Peter Ellenshaw is a lost art. The same can’t be said of Alice, whose art deserves to be lost.