“Every epoch dreams its successor”

Jules Michelet

In the grand pantheon of sci-fi cinema, no other film is as boldly revolutionary or influential as Fritz Lang’s 1927 masterpiece, Metropolis. Watching it today, the silent epic has lost none of its invention, societal prescience, visual splendor, or emotional resonance. It’s hard to imagine a world without Metropolis; a world without sprawling cityscapes of the future, robot women, or blistering societal allegory. And with the film now restored to its original glory following the discovery of some missing reels in 2010, it can be enjoyed the way Lang always meant for it to be.

The film concerns itself with a future city, where the working class toil endlessly on the machinery in an underground slum in order to ensure that everything above ground is functioning. It is above ground where the upper class reside, in a city fit for gods and kings alike.

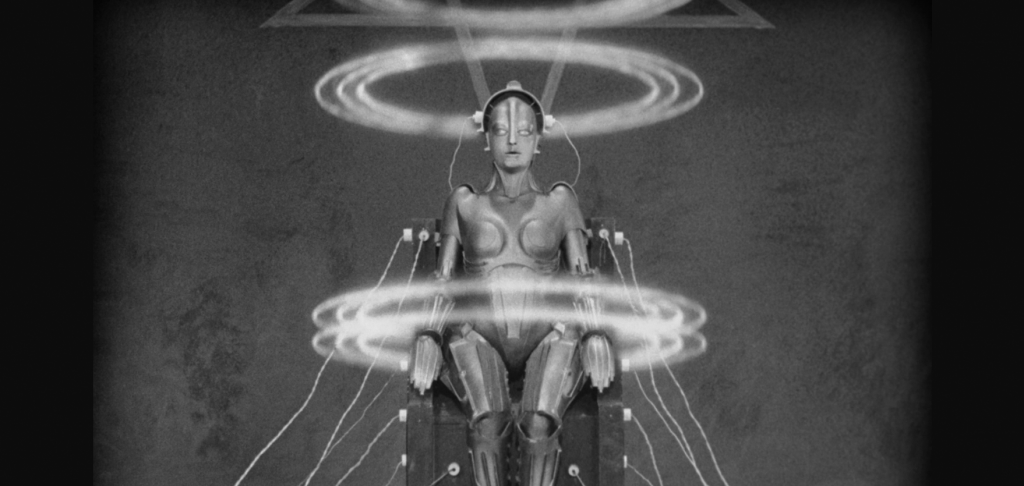

Romance, political intrigue, and a robot woman diabolically programmed to quash societal uprising all factor into the story, set against the backdrop of Lang’s immaculately made city. The environment is rich with detail, imagination and special effects; miniatures and elaborate set designs hold up amazingly well, depicted through Lang’s masterful compositions that stress sloping angles, chiaroscuro lighting, and hundreds upon hundreds of extras.

Metropolis‘s influence can almost always be felt in the field of science fiction, from classics like Blade Runner and Star Wars, to modern films like Minority Report, The Hunger Games, Cloud Atlas, and even Children of Men. Another film that it influenced, inadvertently or otherwise, was the seminal animated film Akira from manga artist and anime director Katsuhiro Otomo.

Whereas Star Wars revolutionized the visual language of the space opera, Akira was an evolution of the futuristic utopia/dystopia that began with Lang’s masterpiece, while also blending elements of punk transgression, teen angst, and even a subversion of superhero origin stories. It, Star Wars, and Blade Runner make for a triptych of films that defined sci-fi in the 70s-80s; films that – like Metropolis – continue to leave a mark on the genre to this day.

But Akira isn’t the only film involving Otomo that managed to leave a lasting impact on sci-fi. In the late 90s and early aughts, Otomo collaborated with Astro Boy director “Rintaro” and the long-deceased manga writer Osamu Tezuka. With three visionaries in the field together, the team sought to utilize the most cutting-edge 2D and CG animation to create both the ultimate sci-fi film and the ultimate animated one.

The result was 2001’s Metropolis, directed by Rintaro, and written for the screen by Otomo from Tezuka’s 1949 manga of the same name. The film received rave reviews from both Japanese and American critics alike, only to flop with a worldwide gross of $4 million, not even close to its $15 million budget. Nor did it ever receive the same cult status enjoyed by other classic animes like Ghost in the Shell, Ninja Scroll, and Otomo’s own Akira.

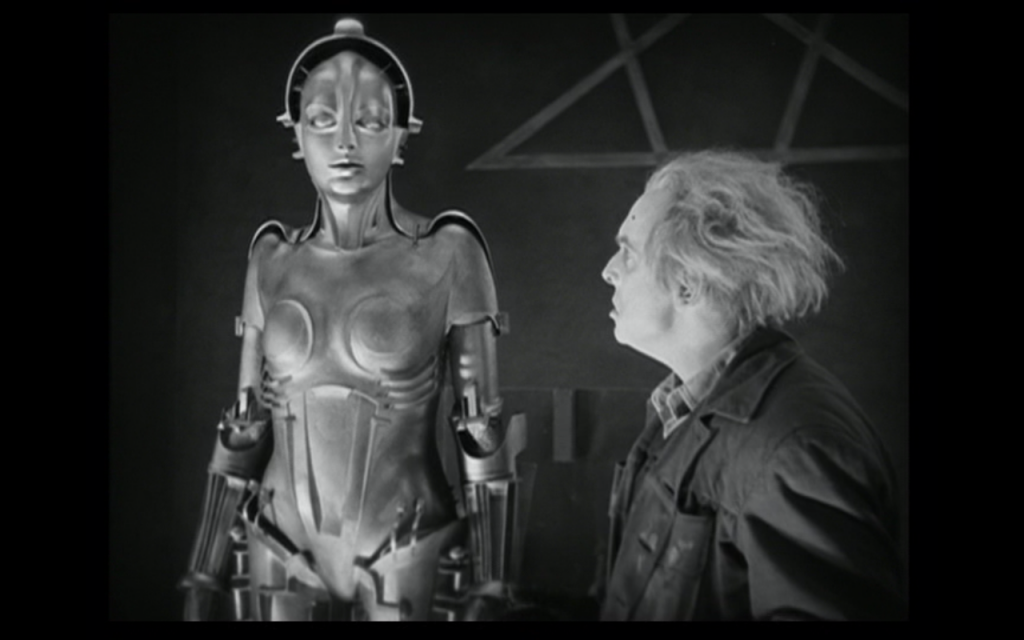

According to Tezuka, he wasn’t really thinking about Lang’s film when he wrote and illustrated the manga, stating that the only image he explicitly took from Lang was of a robotic woman being “born” from the hands and mind of a mad scientist. It’s impossible to say for certain whether Rintaro had Lang on the mind, but it would certainly be hard to believe otherwise. It’s also believed that it was Otomo, the screenwriter, who brought Lang’s influence to the film. This new Metropolis has enough similarities to be considered a remake, but also enough huge differences to elevate it from such relatively simplistic term. Rintaro and Otomo don’t just borrow from the story – they expand upon it.

The 2001 Metropolis also takes place in a futuristic city that consists of multiple “levels” above and below ground. In Lang’s film, the lower levels housed lower-class human workers. Rintaro’s feature takes that basic idea and gives it an interesting spin that adds shades of Blade Runner and A.I. Artificial Intelligence: the lower levels are made up of robotic servants that keep the humans living in the upper levels intact (the humans themselves still divided by upper and lower class). It’s easy to say that humans are degraded when treated as an inferior class by a societal hierarchy, but do those same rules apply to artificial intelligence, who aren’t human and are literally built to withstand years of toil and work as their one true purpose?

Both films also happen to have a massive skyscraper at the center of the city. Lang’s is called the Tower of Babel, while Rintaro’s is called the Ziggurat – which is a more generalized term for Lang’s Babel. The original’s themes of fathers and sons also factors into Rintaro’s Metropolis, but of course, they too have been altered somewhat. Whereas Lang’s protagonist was the son of Metropolis’s “leader” of sorts, the step-son of Rintaro’s “Duke Red”, who rules over Metropolis, is a multi-faceted villain who sets out to capture the robot girl that will fulfill his surrogate father’s political desires, and kill her out of jealousy and desperation to please his father.

Speaking of which, there is a robot girl in the 2001 Metropolis as well, but unlike Lang’s film, she’s not a villain programmed to topple the workers’ rebellion. She was, like Lang’s robot woman, designed for nefarious purposes, but when an assassin kills her creator, Dr. Charles Laughton (referencing the great Hollywood actor and one-time director) and leaves her in the care of a young boy from Japan named Kenichi and his detective uncle, she forgoes her programming and ends up befriending and then falling in love with the kid – who names her Tima.

Sooner or later, she’s torn between her human emotions and robotic programming – a brilliant twist on the robotic woman of Lang’s film, who assumes the role of the hero’s love interest. Both the human and robot woman are played by the same actress, one representing the kindness of the human spirit, the other personifying the cold objective-based thinking of machinery. Rintaro’s film puts the two of them together, and makes their battle internalized and, thus, more complex.

It is through the inclusion of artificial intelligence that Rintaro and Otomo not only differentiate their film from Lang’s classic, but also take the 1927 version to its logical conclusion. And yet, there’s so much more to it than just mere differentiation. It’s not out of flattery or coincidence that Rintaro’s shiny new animated film is named after its great great silent grandfather. Rather, Rintaro and Otomo use the namesake, intentionally or otherwise, to establish their film not just as a means of honoring Lang’s, but also as a celebration of how far science-fiction (and indeed, cinema) has gone since the days of Lang in late 20s.

Whereas Lang’s Metropolis practically “founded” the cinematic science-fiction epic – expanding upon what Georges Méliès began with his silent films, considered to be the very first science-fiction and fantasy films ever made – Rintaro and Otomo have made a film of startling compilation, bringing together the themes and ideas of almost every other science-fiction film to follow in Lang’s footsteps: from the dystopia/utopia laced with allegorical themes found in Lang’s original, the more existential questions of human existence and artificial intelligence one might find in Blade Runner, the adventurous spirit of Star Wars, and astounding animated detail found in Otomo’s own Akira. Intentionally or not, that is what they’ve accomplished.

Speaking of the film’s animated format, it also manages to display not just how far sci-fi has progressed, but also the advancements of the filmmaking medium at large. Fritz Lang made his film as a silent picture without sound, in black and white, with elaborately designed sets and models used to practically accomplish his vision. Rintaro’s film, meanwhile, is the exact opposite: bursting with vibrant color, elaborate in its use of sound, born out of a mixture of hand-drawn animation and computer-generated effects.

Similarly, while Lang’s film features a rapturous score of classical orchestral pieces, Rintaro used New Orleans style jazz to get with the times. As we bear witness to this monument of the future, all we hear are the sounds of the past, echoing still years after their creators have passed on. Lang’s music has the grace and class of a Philharmonic orchestra, a sound that is timeless and eternal, and yet reached for the grand potential of the future. Rintaro’s has the soul of the past, just playing in the moment, unable to see how the song will end in the future. One yearns for tomorrow; the other builds from the roots of yesterday.

That same presence of “soul” can be attributed to Tima, who despite being an artificial creation, has the spirit of a being that is truly alive. A lot of the film languishes on just her face and those huge, doll-like anime eyes, staring in wide-eyed wonder at the bustling world around her. Like Samantha from Spike Jonze’s Her, we almost forget that this is an artificial intelligence we’re seeing; so focused are we on the human soul within.

When the antagonists of the film eventually capture her and set her back to her original programming – to power a mighty superweapon to be used for war – it complicates the issue further. In Spielberg’s A.I. Artificial Intelligence, which released the same year, the robot boy David’s programming and his human emotions were one and the same, blurring the line between the two. Metropolis‘s depiction is less seamless but in no way less thought-provoking. If human emotions can be overridden by programming, does that make those emotions less valid, and vice versa?

When she’s plugged into the superweapon, Tima becomes more menacing, and thus, more similar to the robot found in Lang’s Metropolis. She becomes so powerful that just charging the weapon blows up a huge chunk of the upper levels of Metropolis. Fritz Lang’s film ended on a more peaceful note, with the climactic fight scene being followed by a treaty between the upper and lower levels. Rintaro’s offers no such peace.

If Rintaro and Otomo’s Metropolitan city was made via compilation of the sci-fi that came since Lang, then it’s interesting that they end their film by demolishing it. Their film isn’t a complex breakdown of sci-fi in the same way that Drew Goddard’s The Cabin in the Woods broke down the horror genre. Rather, it’s a literal breakdown. They’ve taken everything they’ve loved and learned from science fiction over the years, and brought it all crashing to the floor – with Tima being destroyed along the way.

This destruction is seen by the filmmakers as beautiful, with Rintaro brilliantly injecting Ray Charles’ “I Can’t Stop Loving You” into the soundtrack (it’s the best use of licensed music since Fight Club‘s “Where is My Mind”), creating musical dissonance between the beauty of Charles’ music and the wanton obliteration of the city. What is the gain of this act of destruction? For a while, it seems as if it was all for nothing, plot-wise and thematically. Man’s obsession with power by way of technological advancement slips up yet again. Big whoop.

But it isn’t until the final shot of the film that the meaning of Rintaro and Otomo’s destruction is revealed, as the camera moves deep into the ruins of the Metropolis, and we see a radio, left behind by Tima, that utters her last words:

“Who am I? I am who?”

In a way, that’s what all of the best, most thoughtful science-fiction boils down to: what is it that defines a human being? That is the core of sci-fi. Rintaro and Otomo break apart all of the genre’s conventions to get to the one question that they all share: “Who am I?”

Rintaro and Otomo take the visuals, conventions, and themes we all know and love from sci-fi, that were brought about by Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, and then smash them to the ground. In doing so, they return to the core that Lang worked so hard to explore. Lang started from that basis, and looked up into the future. Now that we’ve made it there, Rintaro and Otomo look back down again at the core that started it all.

And every epoch dreams of its successor once more.

4 thoughts on “A Tale of Two Cities: Rebuilding a Metropolis”

13 years later apparently the ending of the Metropolis anime still gives me chills. Wow.

Interesting that there’s no mention of the religious imagery and context in Lang’s Metropolis…

The religious aspects are rather obvious in Lang’s (the Tower of Bable sequence that literally recreates the Biblical story), but Rintaro’s film didn’t concern itself with those themes all that much, so I didn’t focus on them nearly as much either. That being said, I’m glad you brought it up, because I would’ve loved to have added a paragraph or two about it, but the piece was already rather long.

$4 million is a box office from several countries other than Japan (NA and Europe).