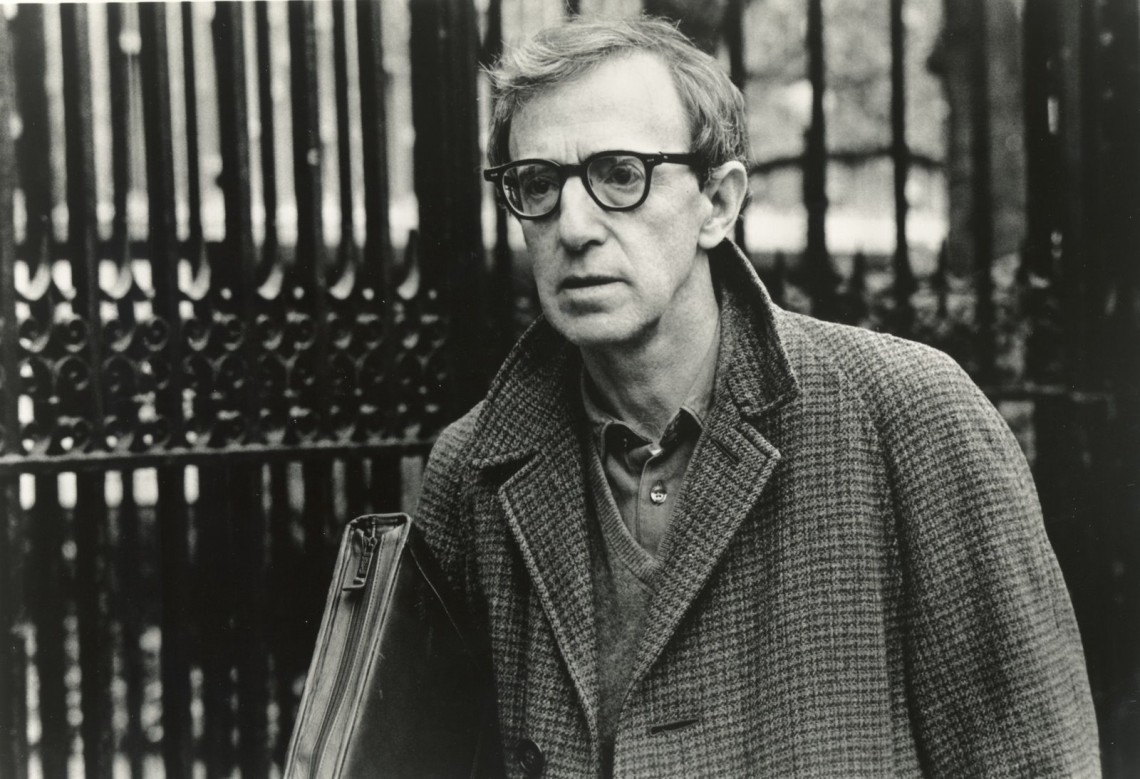

Movie Mezzanine is proud to bring you an excerpt from Jason Bailey’s latest book, The Ultimate Woody Allen Film Companion. If you enjoy the following passage, be sure to purchase it here.

“I can never bear seeing a headline like ‘Woody Dying to Be Taken Seriously.’ It misses the point entirely. I don’t want to be taken seriously. I have to be taken seriously.”

—Woody Allen

Looking back on the afternoons when he would dash off dozens of jokes during the subway ride to his first paid writing job, Woody told Richard Schickel, simply, “If you can do it, there’s nothing to it. You know, it’s like drawing. I can’t draw, so I’m astonished at a kid sitting next to me in class who will draw a rabbit or something. I’m amazed by it. For him it’s nothing, and he wonders why I can’t do it. . . . Well, I could write jokes, so there was nothing to it.”

That something so remarkable came (and continues to come) so easily to Woody Allen goes a long way toward explaining why, from almost the beginning of his career, making people laugh has never been enough. As early as 1976, he was confessing his desire to do “more serious comical films and do different types of films, maybe write and direct a drama.” The aim was clear: to “take chances—I would like to fail a little for the public.

When he followed up the Oscar-winning critical and box office success of Annie Hall with the dour Interiors, he certainly got that opportunity. The move came partially from a desire, seen in Annie Hall, to make films that were more than “just” comedies. “As soon as you start to want to say something meaningful in comedy,” he explained at the time, “you have to give up some of the comedy in some way.” But more than anything, Allen wanted to make a film that achieved a gravitas he felt simply wasn’t within the grasp of comic work. “There’s no question that comedy is harder to do than serious stuff,” he said in 1972. “There’s also no question in my mind that comedy is less valuable than serious stuff. . . . I don’t want to sound brutal, but there’s something immature, something second-rate in terms of satisfaction when comedy is compared to drama.”

True enough. But what made Interiors difficult for so many viewers to embrace was that it was such a stark departure, such a 180-degree turn from the output that had come before it. Though undeniably a film of skill and value, it also dispensed with much of what made Woody interesting, from the naturalistic, vernacular dialogue of Annie Hall to the rough energy of even a story-driven knockabout comedy like Sleeper. “He created such an original comic outlook and voice that any subsequent attempt at drama jarred the sensibilities of many in his audience,” theorized biographer Eric Lax. It’s not a film without humor—the character of Pearl is not only a breath of fresh air, but her no-nonsense approach to the thought-provoking play the family discusses at dinner almost seems like an inside joke, Woody having a chuckle at his own serious pretentions.

To his credit, Allen has never blamed his audience for resisting his serious streak. “I hoped they would come with me, but they didn’t,” he said of the reaction to the film, and he rebukes the notion that his audience left him. “I left my audience is what really happened; they didn’t leave me. They were as nice as could be. If I had kept making Manhattan or Annie Hall—the same kind of pictures—they were fully prepared to meet me halfway.”

But Allen has never been the kind of film artist who could keep making “the same kind of pictures.” “I expect more of myself,” he said, “and the audience does, too.” He may have rebounded from Interiors with Manhattan, another comedy concerning the romantic entanglements of New York intellectuals, with himself back in a starring role, but he was still moving forward: His primary focus was no longer on jokes and laughs, but on conflict and character. He smuggled serious scenes and subject matter into Purple Rose of Cairo and Hannah and Her Sisters, and cashed in their success with two more straightforward dramas, September and Another Woman. The reviews and box office were no kinder, but Allen was sanguine. “Those three dramas,” he said, “were very ambitious. So when I struck out, it was apparent and egregious and not entertaining. The impulse was honorable, the attempt was honorable, I did the best I could.”

Those films—which People magazine sneeringly dubbed “the trilogy from hell”—may be problematic, but they were vital to his development as an artist. Each film in the Allen filmography seems a necessary bridge to the next, and he simply may have needed to get those straight-faced chamber dramas out of his system in order to arrive at Crimes and Misdemeanors, a magnificent fusion of what he did best and what he desired so badly to do as well.

One can view Crimes as the amateur magician performing an epic feat of audience diversion, distracting them with the familiar comic elements while drawing them in to the serious, powerful narrative in the picture’s other half. But more importantly, Allen realized that he need not cordon off his comic gifts. The serious, thoughtful stories he wishes to tell can be cut with a healthy mea- sure of comedy (Crimes, Melinda and Melinda) or thriller (Match Point, Cassandra’s Dream) to make them less drab and more palatable.

He would soon come to realize that the compartmentalization of comedy and drama, either from film to film or within the same projects, wasn’t necessary either. In 1984, he voiced a desire to “constantly alternate between comedy and seriousness”; a decade later, he would confess an interest in “the attempt to try and make comedies that have a serious or tragic dimension to them.” This seems the true achievement of recent pictures like Vicky Cristina Barcelona and Blue Jasmine: the filmmaker’s happy discovery that comedy and drama can not only comingle, but complement.