For decades, Brazilian photojournalist Sebastião Salgado has been one of the most celebrated social photographers in the world. He gets his due in the new documentary The Salt of the Earth, which both recounts his life and work, and uses both as a lens through which to look at the issues affecting impoverished people the world over, as well as the relationship between a photographer and his subject. The film was directed by Wim Wenders and Juliano Ribeiro Salgado, Sebastião’s son. We spoke with both of them at last year’s AFI Fest about the elder Salgado’s work and their unusual process of collaboration.

MOVIE MEZZANINE

What brought the two of you together to make this film?

WIM WENDERS

I have mentioned to too many people that my favorite photographer on this planet is Sebastião Salgado. And finally I realized it was really a waste that I didn’t know him. I kept talking about him and I kept recommending his work and I gave his books to people, and then I realized, “Hey, this man is still alive and working, and I’m still alive and working, and how come I never made an effort to meet him?” So I went and saw him in Paris in 2009, and we got along and talked, and eventually I met his son at a dinner. I realized he was a gifted young fellow. Again, he started to tell me about a project he and his dad had. And one thing came to another and…

JULIANO SALGADO

We had this common intuition. For 40 years, Sebastião has been in many of the most difficult places and been a witness to some of the most important events in recent history. But he had a different take on those things, because of the way he travels. He always spends a lot of time in the places he’s going to photograph. He actually bonds with people. He visits them. So by the time he came back, he had a lot to say about all his experiences. And Wim and I both had the same intuition: Those experiences, those stories, they were very important. And we had to share it.

MOVIE MEZZANINE

Was the plan always that you’d both co-direct?

WIM WENDERS

Yes and no. Somehow we thought it would be interesting to throw our lots together and combine these two points of view: the son and the stranger (or the friend that I slowly became). But we never shot together. Our collaboration really only started in the editing room, and even there it didn’t start right away. He edited his stuff and I edited my stuff. And then we tried to combine, until we realized that we were never going to make a movie together this way, he with his stuff and me with my stuff.

So we either had to start making two separate movies (and we both could have easily made one each) or dare to actually make this one together. And that meant that I let him touch my shots, and I fiddled around with his, and it didn’t matter anymore who shot what. We just had to make it a common film. And that common film is greater than the two separate ones we could have made.

MOVIE MEZZANINE

Documentaries have a certain “standard” approach to using photographs—that Ken Burns pan and/or zoom effect. There’s nothing like that in this film. I don’t believe we ever see a photo even move…

WIM WENDERS

We never fucked around with a single photograph. There is no pan, there is no zoom. We show the work as you would see it if it was a print in front of you.

JULIANO SALGADO

There is movement to photography. You look at it, and the person who took it starts telling you about what’s happened there, what details you should look at. Suddenly, the whole meaning of the photograph is changed. That creates movement. Your understanding of the photo is actually moving. So there is a lot of movement in the film, although the photos themselves don’t move.

WIM WENDERS

If anybody thinks there is a rule about how to show photographs in a film, they have no idea. Actually, we ourselves didn’t have any idea. I edited this film and the photographs for a year and a half. And I’d seen these pictures before. We had the prints in front of us. We had books. And then we edited the film and I saw them on a monitor. And then finally one day, for the first time we saw the film on a big screen, and we saw the same pictures we had now lived with for three years, and it was mind-boggling. I tell you, I thought I’d never seen a photograph in my life before until we saw them in these high-resolution images on a giant movie screen. And that’s why it matters to see the film on a movie screen: because the photos transform. They completely transform into a whole different realm.

MOVIE MEZZANINE

And for the photographs themselves…obviously his work is very famous. How much did you want to explore the photographs that everyone knows, versus others that might be more obscure?

JULIANO SALGADO

We wanted to understand a little about the experiences that Sebastião had. So it was more about how he had progressed into being the photographer that we know…how he had learned to travel and found a place for his photography…what role it could play. That was more what drove us, rather than specific photographs.

WIM WENDERS

Some of the pictures we show are very well-known, while some are not. In the editing, it was strictly his stories that dictated which photos we chose. There was no other consideration than the context itself.

MOVIE MEZZANINE

And are there any excerpts from his life that didn’t make it into the film that you wish had?

WIM WENDERS

Yeah. Oh boy, oh boy. Our rough cut was eight hours. The interviews that we took with his photography alone…if you watched them in real time, it would probably take you two weeks to get through it all. We were quite extensive. At the start, we didn’t realize we were dealing with a man who was quite clever and who dedicated so much time to his dream. He’s not the kind of photographer who flies in, takes his picture, then leaves the next day. He stays for three months. And that’s what makes the difference with his photography. We realized we had to give it the same amount of time. His work forced us to that. The amazing stories we had to leave out…I mean, that’s the editing process, and the film does touch on all the principles of his life. We just left out a few—a handful, maybe.

MOVIE MEZZANINE

You have an unusual style of interview in this film. Salgado looks directly at the camera, while the audience sees whatever photograph he’s looking at and talking about laid over his face. How did this method come about?

WIM WENDERS

I shot for weeks rather conventionally with two or three cameras, just Sebastião and myself. I asked him lots of questions, but I was in the shot as well. He talked to me and explained things to me and we looked at books and stacks of photos—hundreds and thousands of photos. By the end, I knew his whole photographic worth, and I also knew that none of this was going to be in the film. It slowly dawned on me that my whole approach to interviewing him was wrong.

The only moments in these weeks and weeks of interviews that were valid were the ones where he forgot he was being interviewed. When a picture had caught his attention, it was as though he became really immersed in the experience, like he had total recall and was back in it. And then he’d look up at me and it became an interview again. I realized I didn’t have a movie and we had to start from scratch. Luckily, the producer went along, and by then we’d conceived a completely different method.

I realized that I had to let him be alone with the photographs. So we created a dark room where there’s nothing to see. There’s no crew, no cameras, just a screen with his photographs. And the screen was on a semitransparent mirror. It was like a teleprompter, but it didn’t show text—it showed his photographs. And while looking at his photographs and talking about them, completely immersing in them in this dark room, he was at the same time looking into the camera. He was intimate with his photographs and he shared it with us. I was behind the camera and could control the flow of the photos or ask a question, but without taking him out of the memory.

MOVIE MEZZANINE

That’s fascinating. It sounds similar to Errol Morris’s Interrotron.

WIM WENDERS

I know of it, but that’s still another thing. In Errol Morris’s procedure, through the mirrors, the interviewee sees him while looking into the camera. Here, the interviewee sees his work while looking at the camera.

JULIANO SALGADO

The whole thing’s about memory. As Sebastião’s confronted with the pictures, the moment he’s coming back from his thoughts, Wim, without asking a question, changes the picture, and the next moment comes to Sebastião. It was so powerful. Sebastião couldn’t be in there for more than 10 minutes at a time, because he was really traveling back into his memory, traveling through time, you understand.

MOVIE MEZZANINE

Which expeditions did the shoot accompany Salgado on?

JULIANO SALGADO

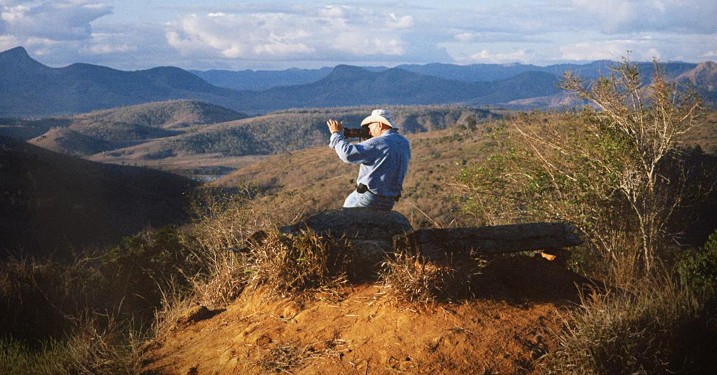

I went with him to Papua [New Guinea], to Brazil, to a Siberian island, and when he visited an Indian tribe that lives in Amazonia—all very isolated areas, where people live a very preserved way of life. The whole point of traveling with him was really to see how he connected with the animals, the places, and the people. It was amazing to see how focused and how driven he is, and how quickly he manages to create bonds with people who are very foreign to us.

He meets people who live life the same way they did 15,000 years ago, and we don’t speak the same language, but within five minutes, Sebastião is having a laugh with them. And they’re starting to have an exchange. Sebastião’s real talent is that he intuitively knows where to put the camera so that the emotions, what’s happening with the person that he’s with, come through the photo.

MOVIE MEZZANINE

Juliano, what was it like to direct a film about your own father? With any documentary, there’s a push and pull between getting intimate with your subject and maintaining a certain remove.

JULIANO SALGADO

It was very complex and difficult. And to be quite frank with you, I didn’t want to do it at first. But as I traveled with Sebastião, we found that we had a complete change of relationship. Somehow, through filming each other, we sort of shared something through those images. When you film someone, usually that imagery doesn’t lie. The place you put the camera, the moment you press “rec,” what details you focus on, the general feeling—a lot of things come out from that. When Sebastião saw the shots I took of him, he was very touched—not because it was good or nice, but because it said a lot about the way I was seeing him. And it played a big role in him opening up to me.

And for me, I thought something like that was going to happen while we were traveling together. But it really happened when I saw all the interviews of him. I knew the stories. Sebastião tells us things when he comes back from his trips. But I had never seen it this way. I’m listening to all his experiences, to all the things that made him change so much. And seeing that as a whole, it allowed me to do a half a step towards him. And that was enough to change everything. So actually, it’s a healing process for us. That’s not really in the film, I think. Or maybe it is, but it’s a tangential thing. It’s implied. But we really healed our relationship.

Now, the film is not about that. It’s about our experiences, and how much we can learn from them, and how he managed to transform when it was impossible to go on the same way any longer. It’s not really about my father. It’s about the photographer and the witness.

WIM WENDERS

For Sebastião, the photos don’t matter. The only thing that matters is that he translates what these people are all about, what their life is all about. He’s the intermediary. He’s a photographer because he realized that photography was the best medium to translate social experience.

MOVIE MEZZANINE

And in the movie, you’re doing that to him. You’re getting him to reveal himself, but in film form instead of through photography.

WIM WENDERS

Totally. And I try, just like him, to disappear myself. We both try to disappear and just let him talk. We didn’t quite manage to do that completely, but we did as well as we could.

MOVIE MEZZANINE

The two of you have a very easy back-and-forth. One can take over where the other finishes. You worked on this project together for four years. How did you evolve as collaborators?

WIM WENDERS

Well, we fought.

JULIANO SALGADO

Yes. Like, big time.

WIM WENDERS

We had fist fights. We beat each other up because he…yeah, no, I won’t say why.

JULIANO SALGADO

But yes, it was difficult. To co-direct a film, even with someone as great as him, the first thing I had to do to be able to work with him was transform him into a film schoolmate, so I could say “No” sometimes. But the thing is that making a film is a gut feeling: what’s right, what’s wrong, what’s driving you into it. And of course, when you have two people with gut feelings, that’s one too many, actually. So before we could understand one another, we had to collaborate in a different way—not with two different approaches, but through consulting with one another, or arguing and shouting sometimes.

WIM WENDERS

It was a tough process. And now we can give interviews together—because we did more important things together. We shared our respected materials with each other, which I’d never done before, and I don’t know if I’m going to do it again. [laughs] So if you make your next film, don’t ask me, buddy!

JULIANO SALGADO

Okay!