According to an article published last year in the New York Times, Rules Don’t Apply, the latest writing/directing effort from Hollywood legend Warren Beatty, has been 40 years in the making, with the death of the film’s subject—the famously reclusive and increasingly eccentric billionaire industrialist Howard Hughes—planting the seeds for a project. The film will finally be released on Wednesday, and many may find themselves surprised by what an altogether strange passion project this is. Hughes’s tumultuous life—already explored onscreen by Martin Scorsese in his 2004 epic The Aviator—is basically turned into a backdrop for a relatively lighthearted romantic comedy-drama led by aspiring Hollywood starlet Marla Mabrey (Lily Collins) and Hughes’ young driver Frank Forbes (Alden Ehrenreich). As a result, the film’s tone keeps slipping around, lurching between broad comedy and serious drama. Even more graceless is the seemingly haphazard way the film has been edited, with scenes either abruptly clipped or relentlessly drawn-out (a possible byproduct of the film having four credited editors). His last directorial effort, Bulworth (1998), wasn’t exactly a polished piece of work on a technical level, but it was nowhere near as formally sloppy as Rules Don’t Apply is.

In other words, Rules Don’t Apply is a total mess: an utterly weird Frankenstein’s monster of a film that stitches together biopic and romance elements in ways that end up muffling both aspects. And yet, the film nevertheless carries a certain fascination from an auteurist perspective, confirming that, though all five of Beatty’s features to date vary in subject matter and style, one thread remains consistent: the maker is, as ever, contemplating his own image.

Consider the similarities between the Howard Hughes depicted in Rules Don’t Apply and Beatty himself. Though Hughes started out his professional life making a name for himself as a Hollywood producer with films like Hell’s Angels and The Outlaw, he eventually branched out into the aviation and real-estate industries as an entrepreneur. Beatty has been similarly wide-ranging in talents, starting out as an actor before trying his hand at producing and directing; he has also been quite active in politics, famously included as part of Democratic Senator George McGovern’s presidential campaign in 1972. But the similarities between them are more than just professional. Just as Howard Hughes developed a reputation as a Lothario among Hollywood elite, famously having affairs with Katharine Hepburn, Ava Gardner, Rita Hayworth, and many others, Beatty was famously linked romantically to many women—including Julie Christie, Barbra Streisand, Cher, and Madonna—throughout the 1970s,’80s, and ’90s before settling down with current wife Annette Bening. Both became reclusive later in their lives, with Hughes basically spending the last 10 years of his life living in hotels, and Beatty having not made or appeared in any films since 2001’s Town & Country, until Rules Don’t Apply. Of course, only Hughes could be said to attribute his reclusiveness to a worsening case of OCD.

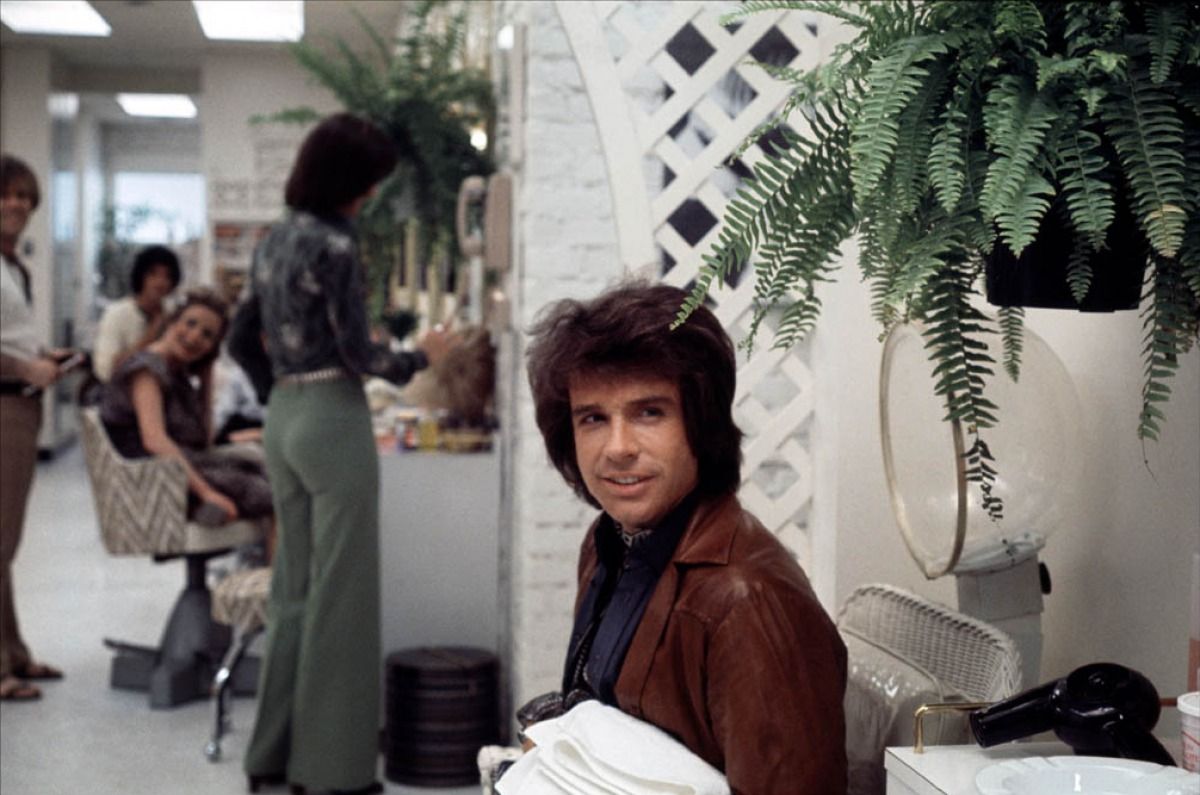

So there is certainly a personal angle to be gleaned from Rules Don’t Apply. But this is hardly a new thing for Beatty. One could go all the way back to not just his directorial debut, 1978’s Heaven Can Wait, but to the Beatty-produced and -starring, Hal Ashby-directed 1975 film Shampoo to sense how interested he is in exploring his own off-screen life through the movies he makes. In Shampoo, Beatty plays George, a hairstylist with a penchant for bed-hopping among a bunch of his female clients. But there’s a deeper political level to Ashby’s film, too: It’s set on the eve of Richard Nixon’s election as President of the United States in 1968. Just as Nixon’s presidency is widely considered to have ushered in the kind of disillusionment that characterized the ’70s after the idealism of the ’60s, so too does George end up all alone at the end of Shampoo after having flown high sexually earlier on.

If Shampoo suggested anything, it’s that Beatty was willing to view himself critically, subverting his own vanity even as he occasionally indulged in it. That humility wasn’t really evident in the terminally slight Heaven Can Wait, which, for all its whimsical charms, felt more like a conscious attempt on Beatty’s part to present himself in the most virtuous, crowd-pleasing light possible. (Pauline Kael’s slam of the film as “image-conscious celebrity moviemaking” without “a whisper of personal obsession” in it remains an apt characterization of it even now.) But the personal and the political once again merged in Reds, in which Beatty turned revolutionary journalist John Reed into yet another analogue for himself: a man with deep political passions who, in the free-love environment of 1910s Greenwich Village, also had a notorious penchant for sleeping around, to the consternation of love interest Louise Bryant (Diane Keaton). The role allowed Beatty to fully tap into his reserves of charm and good humor, but unlike Heaven Can Wait, he was willing to come off as unsympathetic at times, especially in the moments when his Communist revolutionary fervor threatens to take a toll on his relationship with Bryant.

Perhaps a bit more vanity might have elevated his next directorial effort, the 1990 comic-book adaptation Dick Tracy, beyond its still-striking look; his colorlessly one-dimensional hero ultimately dissolves behind the film’s extravagantly colorful sets and the scene-stealing grotesque villains played by Al Pacino, Dustin Hoffman and others. He reserved his most daring personal gambit, however, for Bulworth, the 1998 political satire which saw him, playing a disillusioned senator, finally finding the courage to speak the truth about politics and the Democratic Party—though only through adopting street clothes and rapping. Whatever you may think about the film’s politics, or even its roughness as a piece of filmmaking, there remains something bracing about seeing Beatty willing to come off as silly-looking, foolish, and maybe even a little offensive to air out his anger at the party he so publicly supported back in the 1970s.

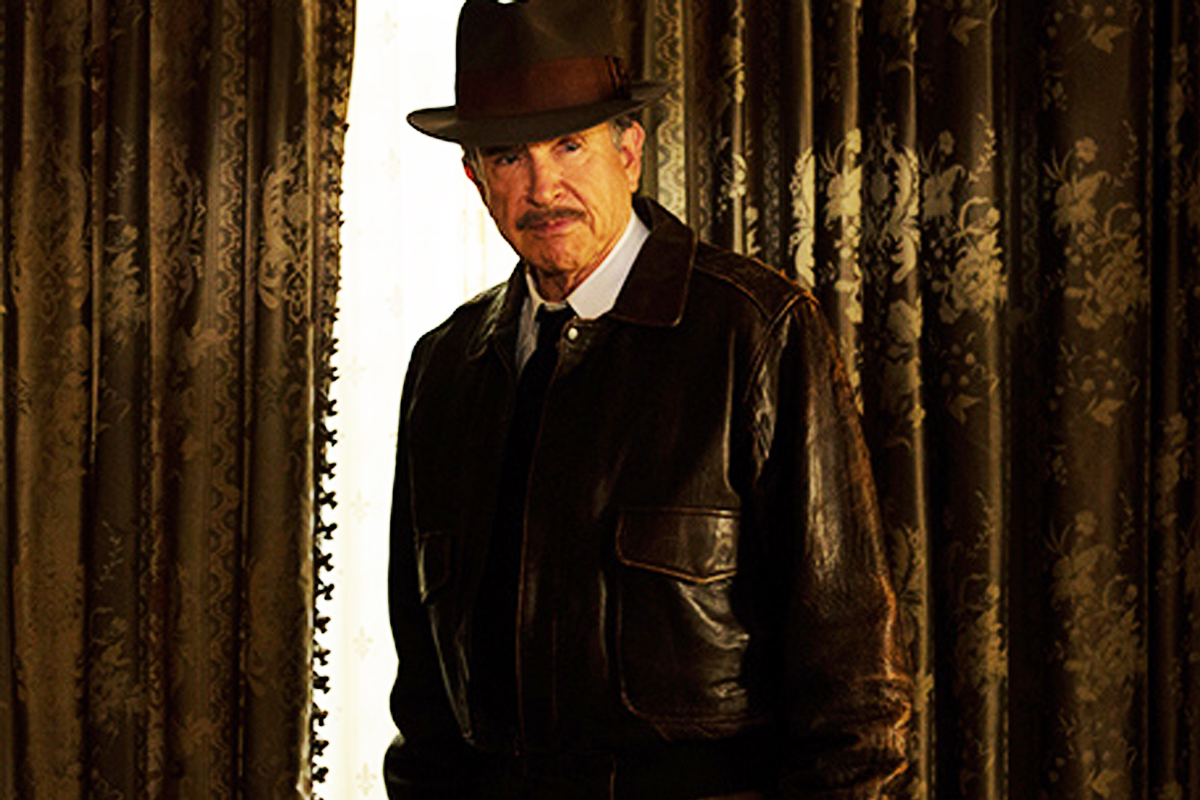

With all that in mind, Rules Don’t Apply could be seen, in its own clumsy ways, as a summation of Beatty’s own views of himself. As Hughes, he gives himself an introduction about half an hour into the film completely bathed in shadow, as if he was hesitant to step into the spotlight after more than a decade away from it. Once we finally get to see his full visage, though, he proceeds to present himself as the sexual dynamo of old, albeit presented here in a way that comes off as more buffoonish than magnetic. (Spoiler alert.) Hughes, however, crosses a line with Marla when he, desperately needing a woman to marry for the sake of his public image, takes advantage of her in a rare moment of inebriation and has sex with her, even going so far as to promise to marry her—a promise he eventually fails to keep. By its final act, as Hughes delves deeper into his OCD-induced psychosis, Beatty has shorn whatever romantic charm he had earlier in the film and become an elusive and inexplicable freak—albeit one who, in the end, ultimately helps to bring Marla and Frank together in their mutual bitter disillusionment toward the Hollywood machine.

Beatty’s final image of himself in Rules Don’t Apply is of him as Hughes closing a curtain around his bed in a hotel room, sickly and visibly aged, about to retreat into what one assumes is a lifetime of seclusion. One can’t help but wonder if this is Beatty’s own way of withdrawing from the world—or maybe he essentially already has, and this odd, unwieldy, yet strangely compelling film is his last gasp before completely retiring from view. Only Beatty, knowing what we know about him and his conflicted views of himself throughout his career, could make that image as poignant in its contemplation of mortality as it is grotesque.