With its near-fetishistic focus on lower-class life, Andrea Arnold’s American Honey unfortunately hews closer to her 2009 film Fish Tank than to the surreal, inventive visions of her 2006 debut Red Road and her 2011 adaptation of Wuthering Heights. When it comes to poverty, as in Fish Tank, it’s not enough for Arnold to show her characters suffering its indignities. She has to rub our noses in it, zeroing in on visual and character details—a whole chicken on a dirty house floor, salmonella seeping out of it; a creepily sexual dance between Star (Sasha Lane) and her father; the utter insensitivity of Star’s estranged mother just as she’s about to flee on the road trip that the film chronicles—that suggest that she’s lavished more imagination in coming up with such miserablist horrors than in envisioning convincing flesh-and-blood characters.

That disinterest in characterization turns out to be the film’s biggest failure. American Honey is ostensibly a love story between Star and Jake (Shia LaBeouf), with both of them experiencing varying degrees of romantic connection and disconnection as they travel across the U.S. with a magazine-sales crew of misfits. But their initial meet-cute at a supermarket is so ridiculously unbelievable—apparently, all it takes for Star is one long, gaga stare at wild-child Jake while he and his crew dance to Rihanna’s “Love in a Hopeless Place” (one of many irritatingly on-the-nose music cues throughout)—that it’s difficult to take their romance seriously from the start. Neither character gains much in dimension or credibility as their road trip progresses.

Many individual scenes stand out throughout the film’s 162 minutes: a picturesque outdoor sex scene that trembles with sensuality, as well as images of wild animals that achieve a rare tactility. Some of the character interactions—especially among Star’s magazine-sales colleagues, all of them similarly recruited from the street—have a refreshing sense of offhand naturalism to them, as if Arnold’s camera simply caught these people on the wing. As the film grinds on, however, the lack of a strong thematic through-line becomes increasingly enervating. It’s as if Arnold intended to make some grand statement about America as a land of deception and reinvention, but never bothered to clarify that vision by adding any details.

There’s a somewhat similar lack of clarity to Michèle Leblanc (Isabelle Huppert), the main character of Elle. In this case, that fuzziness isn’t the result of an incoherent script, but the byproduct of a multifaceted character who may not entirely be the helpless victim we’re initially invited to perceive her as. Paul Verhoeven’s latest introduces its protagonist in the midst of being brutally raped in her home by a masked stranger. Instead of immediately reporting the crime to the police, however, she just tries to go on with her life. The more we get to know Michèle, the thornier she becomes. Among other things, she’s the daughter of a man who was convicted of mass murder in the 1970s, and though she has spent much of her life trying to escape his sordid legacy, her occasional coldness of manner toward friends and relatives suggests some mild sociopathic tendencies that she struggles to keep at bay. Additionally, she’s the CEO of a company that specializes in medieval video games heavy on violence and eroticism, a vocation that suggests a perverse linking of sexuality and brutality in her mind. To top it all off, her attacker continues to threaten her through menacing text messages, thus denying her the ability to forget the rape altogether.

It’s a measure of Verhoeven and screenwriter David Birke’s sincere interest in exploring Michèle’s complicated psychology that, instead of drawing out the whodunit aspects until the very end, the identity of the rapist is revealed about two-thirds of the way through, leading to a last act that blurs the line between sexual violation and pleasure. But Verhoeven has built his career on such reversals of expectations. This is, after all, the same man who dared to present a love story between a Jewish singer-spy and a sympathetic Nazi colonel in his 2006 World War II thriller Black Book. Elle may not offer the unabashed trashiness of films like that one, Robocop, and Showgirls, but, in its own relatively restrained way, it is just as provocative in its attempts to explore disturbing moral ambiguities. To watch Elle is to be perpetually unsure of how to take its alternately sympathetic and unfathomable main character. In other words, it’s Paul Verhoeven at the height of his artistic powers.

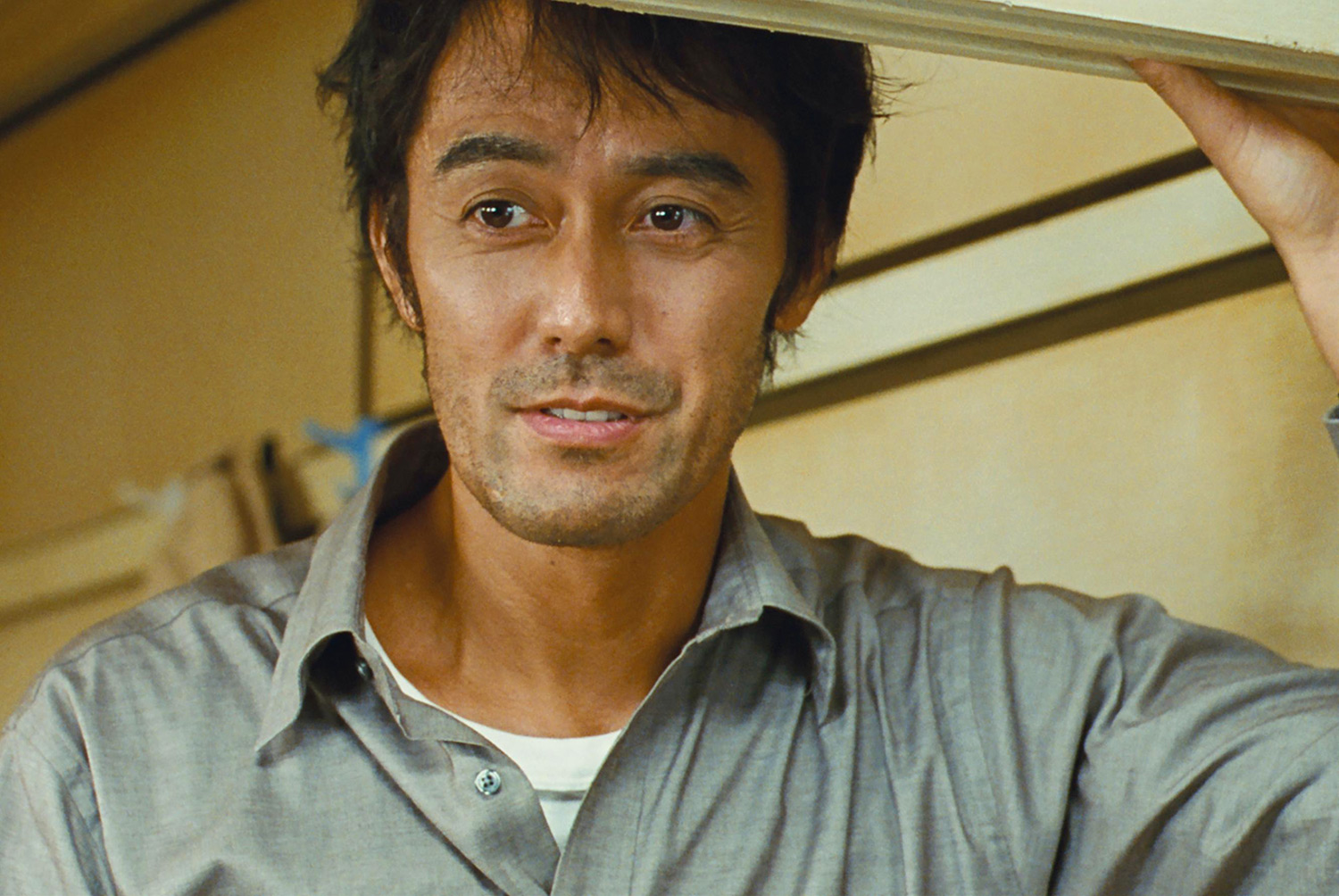

Hirokazu Kore-eda’s new film, After the Storm, presents another study of a deeply flawed character, though one less psychologically troubled than Elle’s Michèle. Instead, Ryota (Hiroshi Abe) is merely a deadbeat. Ryota, a writer who hasn’t followed up his award-winning first book with any substantial work in 15 years, is currently earning his keep as a private detective, though whatever money he earns he usually gambles away, leaving barely enough to pay child support for his son, Shingo (Taiyo Yoshizawa). Though there are suggestions throughout that Ryota is still haunted by the sins of his late father, his broader problem is an inability to let go of his past failures and move forward in his life. Instead, he’s still living off his past literary success, and plagued with regret at allowing his bad habits to lead his wife, Kyoko (Yoko Maki), to divorce him.

Brewing in the film’s background is a gathering typhoon that eventually hits the town in which Ryota, his elderly mother Yoshiko (Kirin Kiki), and his ex-wife and son all live. All of them find themselves forced to hole up in Yoshiko’s apartment to ride out the storm, a circumstance that leads to lots of reflection and attempts at reconciliation and understanding among them all. Kore-eda chronicles all this with his customary warmth and patience; in After the Storm, he’s firmly in his Still Walking and Like Father, Like Son mode, exploring many of the same themes of familial and generational conflict while barely raising his voice above a whisper. Thankfully, whereas Kore-eda’s last film, Our Little Sister, occasionally felt too emotionally reticent for its own good, After the Storm benefits from a lead character with some gratifyingly sharp edges, lending the film real dramatic stakes even as it retains a surface serenity.