Striking compositions. Immaculate execution. Unapologetic provocations. It may sound like the work of a cinematic enfant terrible like Lars von Trier or Harmony Korine, but from the iconic bumsters to the horn adorned jackets to the infamous 12 inch scaled heels (as seen in Lady Gaga’s Bad Romance), it’s the work of an artist on par in another medium: Alexander McQueen and his incomparable pieces of fashion. But, as posited by Metropolitan Museum of Art curator Andrew Bolton, McQueen’s creations were pieces of cinema in and of themselves, each runway show a film in their own right. Inspired by the work of Kubrick, Pollack, and even Friends, McQueen’s artistry was of a singular nature, an amalgamation of great pieces of art, remixed and repurposed to create something entirely new and devastatingly beautiful. In honor of the late fashion icon’s birthday, and the opening of the exhibition Savage Beauty in London, here’s how film influence his fashion.

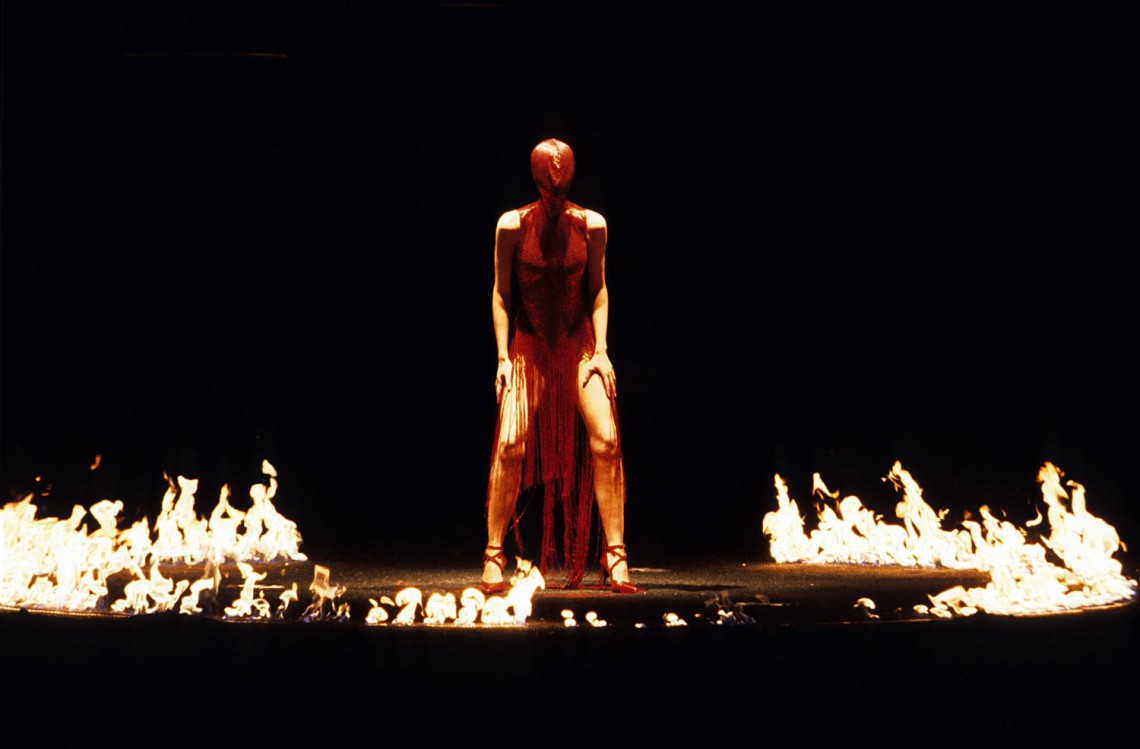

Joan (Autumn/Winter 1998)

For his autumn and winter show in 1998, the British fashion designer crafted a show around the iconic martyr Joan of Arc, and though the immediate connection would be assumed to be Carl Theodor Dreyer’s film The Passion of Joan of Arc, the runway show, which ended in a model draped in red beads, its finale had more in common with the women of the films of Danish auteur Lars von Trier. As Bolton recounts, McQueen was less inclined to use well known models, and when he did, he purposely cloaked their identity in mystery, obstructing it, and destroying it. He, like von Trier, is accused of the same kind of misogyny, one of broken identities and torment, but their defenses are also similar: circled in flame, this Joan is, like Bjork, Watson, and Kidman, trapped by an oppressive environment. But in the end, they all transcend it.

Deliverance (Spring/Summer 2004)

More often than not, multiple pieces of art, in this case film, would go into informing both the collection itself as well as its presentation. Here, John Boorman’s Deliverance and Sydney Pollack’s They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? had equal pull in the creation of McQueen’s spring and summer collection for 2004; the ruinous material speaking to the ragged setting of Boorman’s film, and the dance marathon, filled with once vigorous dancing and now exhausted models, was straight out of Pollack’s. Dragged around, and seemingly abused, this showcase from McQueen also had implications of commentary on model life, each performed utterly exhausted and drained.

It’s Only a Game (Spring/Summer 2005)

It’s a chess game. Two teams, two distinct styles of clothing. The runway is a board, on which the models moved as chess pieces, from one space to another. On the one hand, its framework is an explicit reference to Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, but its examination of international (the United States versus Japan) and class differences came from Peter Weir’s boarding school thriller Picnic at Hanging Rock. Not only was McQueen astute at using fashion as an examination of gender roles and restrictions, but he was just as adept at using the medium, and its presentation, to critique cultural institutions of class and international politics, the latter evident in work like Highland Rape.

The Overlook (Autumn/Winter 1999)

Naming a runway show after the hotel from Kubrick’s The Shining sounds kind of tacky, and the results could have been just as devoid of taste were it handled by anyone else, but given McQueen’s presentation of the show in a gigantic snow globe, the claustrophobia felt and the ice cold desperation that permeates not only the crowd but each piece that a model walks on and off the stage with, solidifies McQueen’s status as a genius. There are identical red headed twin models in the show, nodding to the film, but it’s McQueen’s innovative way of channeling into frigid emotions in his snow inspired collection that cuts to the core.

What a Merry-Go-Round (Autumn/Winter 2001)

Valentino, Prada, and Yves Saint Laurent may be all about the glamour of fashion, but McQueen was always interested in the beautiful in the ugly. His pieces were almost never conventionally beautiful, a side of politics he often explored in works like VOSS. His interest in the macabre aspect of fashion may have peaked with his carnival inspired What a Merry-Go-Round, in which his models were painted by makeup artist Val Garland as a child’s worst nightmare: a scary clown. Set on a fairground reminiscent of Tod Browning’s Freaks, he equally jarring music and general morbid tone of the show was inspired by the child catcher from Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, alluding to the darkness behind seemingly innocuous playthings.