Songs in the Key of Cinema is a bi-weekly look at the use of songs in film and how that music fits within the context of the film as a whole and a place where we’ll cover the moments in cinema that were music to our eyes and ears.

While JK Rowling’s seminal Harry Potter books made a gradual maturation process from book to book, with Goblet of Fire marking a drastic turn in tone and length, the films took a significantly longer time to reach the kind of developed darkness and sophistication that Rowling was able to fairly deftly introduce into her novels. Goblet of Fire was adventurous, Order of the Phoenix only ever hinted at the sinister tone of the book, and Half-Blood Prince played it primarily as a lighter teen comedy. It wasn’t until Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part I that one could feel the show was really about to begin. With each actor bringing their best performances with them, particularly Emma Watson as Hermione Granger, what seemed to solidify a new seriousness for the cinematic franchise was the inclusion of Nick Cave’s beautifully somber “O Children”, a track that would be reflective of both the change in the series and the change in the characters as well.

The Song

Released off of the album Abattoir Blues / The Lyre of Orpheus in September of 2004, “O Children”, the LP’s final track, was never released as a single. The album itself is replete with the kind of grand elegance that is a hallmark of Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds’ work, but “O Children” has a grandeur that is at once restrained and overwhelming. Though to say that the track is produced with minimalist quality would be effectively inaccurate, the restraint of the instruments used (drums, guitar, piano, chorus) is what makes “O Children” feel so grand. Running six minutes long, the immense ballad suggests imagery of Heaven and Hell, and possibly even purgatory.

The Scene

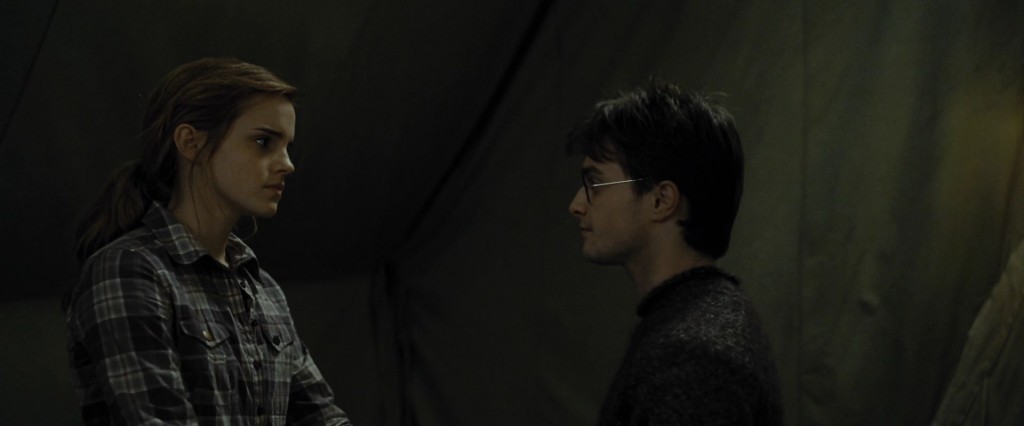

The six minute plus song only appears in the film for about ninety seconds during a scene where Harry (Daniel Radcliffe) and Hermione briefly dance together, making due with the dynamic they’re left with, simultaneously mourning the departure of Ron after a heated argument. As Hermione searches for a radio signal to find some connection to the rest of the Wizarding world, “O Children” comes on. The two dance awkwardly back and forth at Harry’s initiation, primarily to lighten the mood. But Hermione pulls away after a bit, coming to understand the reality of their situation.

The Analysis

As aforementioned, the cinematic incarnation of Harry Potter took longer to make the same kind of dramatic tonal pivots than the novels did, and that’s only understandable to a point. During that time, director David Yates (who handled Order of the Phoenix through both Deathly Hallows films) played around with genre typification, which is almost comparable to the various tonal permutations of the James Bond franchise (from Blaxploitation to sci-fi adventure). But realizing that the film(s) should be representative of the same kind of darkness that Rowling had been peddling anyways, Deathly Hallows was the first to allow that to come to fruition.

I am in the minority in saying this, but Deathly Hallows – Part I is my favorite Harry Potter film because, while it does walk the fine line between self-seriousness and believable moodiness, the nearly European bleakness to the franchise is an absolutely welcome addition. The film burns slowly like the book, making its more exciting moments last with a deeper impact. The emotions of the characters are able to swirl on screen and become palpable to the audience. The tension between the trio now has dramatic flair. The cinematography by Eduardo Serra (What Dreams May Come, Claude Chabrol’s Inspector Bellamy, The Girl with the Pearl Earring) has a precise muted beauty more typical of an art house drama that a multi-billion dollar fantasy franchise film. The Harry Potter series finally matured. It felt like it mattered not only to the past fans of the films and books, but to a more general audience. This one could be taken seriously, and an ironic turn, this wasn’t for children anymore.

Appropriately, Daniel Radcliffe, Emma Watson, and Rupert Grint brought a new grittiness to their roles. The actors have grown up, no long “children” and could imbue their characters with a realism that had been absent for a majority of the series. Adult actors were not dependent on acting off of them, or vice versa: they could now hold their own. Watson in particular was able to show serious dramatic chops in the final two films, her versatility and skill becoming more and more apparent.

Crucial to understanding the song’s place in the film is that symbiotic relationship between the characters and films maturing and the audience itself. Like a lot of nostalgia prone properties, Harry Potter had the good fortune to grow up with its audience, and vice versa. And as one does that, their lives become more complicated and complex. Cave’s song has an ethereal quality that must nonetheless reconcile with reality. The world that Harry exists in is majestic, but it somewhat ironically gravitates much closer to, if not a tangible reality, than an emotional one. “We’re older now, the light is dim, and you are only just beginning,” Nick Cave sings, almost as if he is Potter, the Boy Who Lived.

The Conclusion

Like a Dementor sucked the joy out of the franchise itself, Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part I reached a level of impressiveness and strength that was unprecedented for the series. The complexities of its characters and its themes were finally strong enough to leave an impression, and Nick Cave’s transcendent ballad “O Children” only solidifies that impression. But one can look at the series as a whole with this in mind, “It matters not what someone is born, but what they grow up to be.”