Studio Ghibli’s extended swan song gets a familiar new verse with the English-language dub of 1991’s Only Yesterday. Directed by the animation house’s co-founder Isao Takahata—behind its early social-realist masterpiece Grave of the Fireflies (1988) and its gorgeous last chapter, The Tale of the Princess Kaguya (2014)—the film has long been treated as a respectable b-side to Hayao Miyazaki’s more brand-typical fantastical allegories. Whether it’s thanks to the film’s spotty availability stateside or its markedly earthbound setting, compared to its more celebrated brethren’s castles in the sky, that perception of being minor has overshadowed one of the studio’s most singular efforts. In repackaging Only Yesterday, GKIDS lifts a sheen of dust off a surprisingly ambivalent back-to-nature bildungsroman about a twentysomething who makes a rural retreat as an adult only to find her urbanite 10-year-old self in the rearview.

After an economical opening that cuts from a slow tilt up a Tokyo skyscraper to the monotonous clang of an office keyboard, we focus on melancholy desk drone Taeko (voiced in the dub by The Force Awakens’ Daisy Ridley). Unmarried and by her family’s standards undistinguished at 27, Taeko decides to take a trip to the countryside, committing her city-smooth hands to the laborious farm work of her in-law’s younger brother Toshio (voiced by Dev Patel). Though she hopes the train ride will jolt her out of the stultifying routines of her present, Taeko finds herself awash in lightly burnished memories of her childhood, fixating on 1966. If most people remember that as the year the Beatles came to Japan, for Taeko, we learn, it’s “just the fifth grade.”

Taeko’s modesty in disclosing the scope of her reminiscences reflects Takahata’s own project, which is to gently tug on the threads of the past without forcefully tracing them to the present. Takahata’s attention to the incongruous details that make up most people’s recollections of their adolescence is likely what has relegated the film to second-class status as one of the studio’s apparently lesser adult-oriented dramas. Yet that tendency to stay squarely in its lane rather than reach for greater significance is also what grants the film its peculiar texture and its quietly self-assured tone. Where lesser films about memory seek to turn every recollection into a key that might unlock who a person is today, Takahata stubbornly resists mining such easy meaning out of Taeko’s flashbacks for the better part of the film.

By taking in most of her recollections from emotionally charged baseball games to the bodily alienation of puberty at face value, Takahata allows us to linger in the discomfort as well as the sensory pleasure of Taeko’s involuntary memories of youth. Consider one masterful set piece involving the rare acquisition of a pineapple that turns to be a dud. Once the family has ritualistically carved the fruit, known to them mostly from movies, Takahata tracks the shift from their anticipation to their deflation over its dryness in close-up, staying tight on Taeko’s slightly sinking expression as the taste sets in. Her father’s slowly exhaled pipe smoke fills the screen in the next wide shot, a dull punctuation mark bringing the episode to a close before anyone has learned any important life lessons from it.

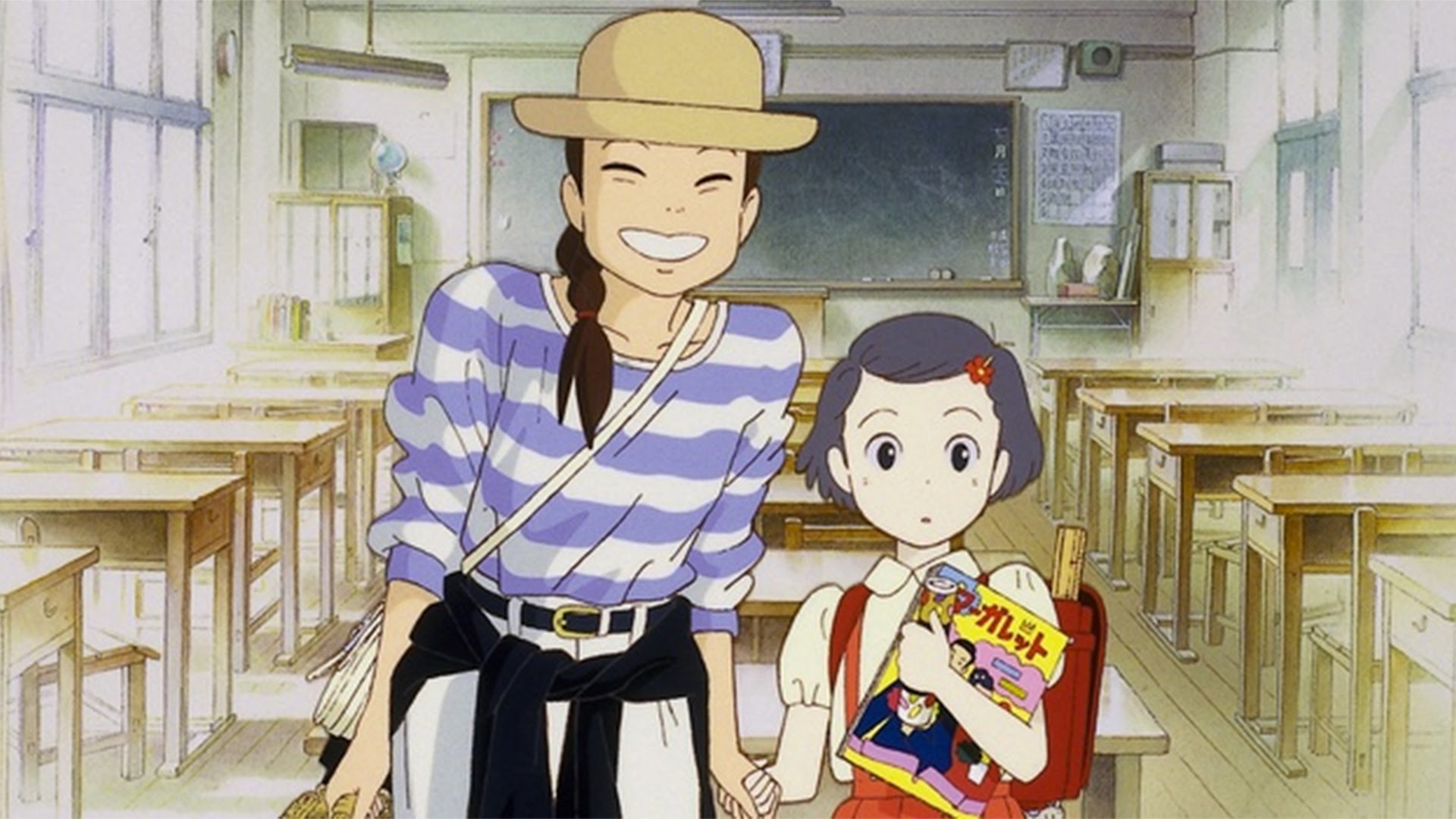

Takahata’s method in dusting off these fragments with painful realism is subtly explicated in one of Taeko’s more trenchant memories, where she impressed her audience at a school pageant by playing a scene as written but closing with an impromptu wave of the hand. That surplus human gesture, uncalled for but critical to the conviction of the performance, is characteristic of Takahata’s own gestural style. To be sure, he relies on other, more distinctive aesthetic flourishes to depict the past — for instance, casting Taeko’s memories as faded watercolors with slightly flattened backgrounds relative to her experiences in the present. One traumatic memory of her father’s rare corporal punishment even disrupts the boundaries of the film image, his slap freezing the memory into a tableau that pushes into the center screen as a framed rectangle, surrounded by white noise. For the most part, though, Takahata is content to realize the past through these delicate gestures.

Only Yesterday’s memory-lane stroll only goes awry in the strange, perhaps productively inscrutable closing act, which seeks to consolidate Taeko’s fifth-grade experiences around a single event while speaking to her current present dilemma over whether to stay in the country and marry Toshio or return to the city. Owing in part to Ridley’s velvety but stilted line readings (including an odd invocation of African-American southern vernacular that’s lost in multiple waves of translation), the older Taeko doesn’t quite scan as the black sheep we see in her flashbacks, which mutes her ostensibly powerful present-tense recollection of a failed moment of intimacy with a poor classmate. Her nascent Marxist account of the harvesting and industrial processing of the safflower likewise rings false, along with Toshio’s insistence, perhaps only to a woman who might make a good companion but more likely also to the urban spectator, that “we have to think about getting back to real agriculture as it was.”

It’s to Takahata’s credit, though, that we aren’t so sure whether to finally read Toshio as a righteous agricultural crusader — and by extension a good romantic match for Taeko as well as the ecologically conscious Studio Ghibli’s hero par excellence — or the prototypical preening farm-to-table hipster. (That he only listens to audio cassettes of rural folk songs in various languages and dialects should give fuel to spectators in both camps.) In the end, Only Yesterday is as gentle and non-coercive as Toshio is strident, even allowing Taeko’s realization about her childhood behavior, and where it brought her, to register as at most a half-epiphany about her still developing subjectivity — more a question than an exclamation mark at the end of a long dialogue with the past. Some might find this inconclusiveness frustrating, but it’s entirely of a piece with the humbleness of Takahata’s storytelling, signaled from his aesthetic decisions right down to the “only” of the title’s English translation.

Original illustration by Emily Peck.