Mia Madre, the latest film from Cannes festival darling, Nanni Moretti, is a companion piece of sorts to his 2001 Palm d’Or-winner, The Son’s Room. That film, which dealt with the loss of a child, is the more emotionally successful affair; a parent burying their offspring carries the extra wallop of a violation of the natural order of things. Facing the more anticipated notion of a parent’s precedence in death can still obviously be devastating, yet Mia Madre feels cold, indifferent and at times condescending toward its protagonist. There’s a pervasive flatness to the proceedings that is only alleviated by a character who is literally appearing in another film.

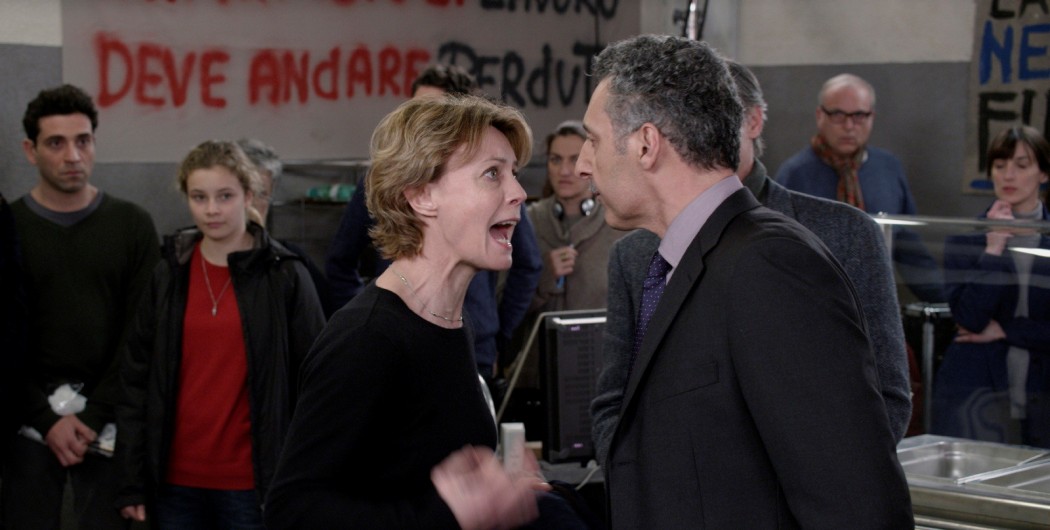

Margherita (Margherita Buy) is a director whose latest picture, a drama about a labor dispute, is causing her distress. Her directorial comments and demands make no sense to her actors, and she’s easily prone to outbursts that seem equally as illogical. In addition to her job demands, she is in the midst of a break-up with her actor boyfriend and raising a daughter who’s currently flunking Latin in school. Margherita is barely outmaneuvering a breakdown before she gets word of her mother Ada’s terminal illness.

Ada (Giulia Lazzarini) is a beloved Latin teacher whose students adore her. She is doted upon by her son Giovanni (played by the director), a man who, unlike Margherita, has tired of his career and refocused his energies elsewhere. Ada is the mother of the title, and while one might assume that her presence (and absence) will haunt the corridors of Mia Madre, Moretti has other ideas. Though Margherita visits her mother every night, the lethargic, bland interactions between the two give the impression that Ada’s impending demise is more an inconvenience than a tragedy. It is clear from the lack of information provided about the characters that we are meant to infer the details, but there is little of interest to make the audience’s work worthwhile.

Mia Madre tiptoes around Margherita’s inability to process her grief, and rather than seem like a conceit that trusts the audience to fill in the blanks, all the suggestions and minor hints come off as coy and frustrating. They do little to enrich the character, despite Buy’s best efforts to portray a woman who feels inadequate when compared to her brother, her daughter and her contemporaries. Also weakening the main story are flashbacks and memories that are incoherently worked into the narrative, and an additional comic side story that is far more effectively told.

That side story proves to be Mia Madre’s secret weapon and the one element of the film that truly succeeds. Buy is an actor whom I love to see doing a job onscreen (her 2014 film, A Five Star Life, is a worthy example of this). The scenes where she is directing her film are played for a high comedy that clashes with the melodrama while providing a welcome respite. Most of the credit in this subplot goes to John Turturro, who fearlessly dives into the over-the-top role of Barry Huggins, a terrible, temperamental American actor hired by Margherita for no discernible reason. He can never remember his lines, speaks terrible Italian and spins wild, untrue tales of working with “Stanley” (as in Kubrick).

Turturro is excellent here; it’s as if he’s channeling Scent of a Woman-era Pacino through a John Cassavettes movie. You want to spin his force of nature out of the movie, then follow him so Ada’s family can deal with their sadness undisturbed. His scenes with Buy have an honest, comic energy — for once we can side with Margherita and feel her aggravation — and his dance number near the end of the film is a small master class in physical comedy (his fake driving scene is also laugh-out-loud funny). “I play the fool in this movie,” Turturro told the NYFF crowd during a Q&A – and while he’s right, he’s also the one character who is allowed to be fully formed, no matter how silly he may be.