The unrepentant dandy of a critic Addison DeWitt (George Sanders) in All About Eve (1950) wields his influence like the magic of a Faustian Satan, manipulating stars and playwrights with nothing but the threat of a review. Yet he stands from society, distanced by sexuality just ambiguous enough to appease the Hayes code. It’s a model of 19th-century romanticism, the gifted individual whose opinions shape the mass consciousness, but one revisited recently with the infallible food critic Anton Ego in Ratatouille (2007). But while Ego’s refined manners and unquestioned influence echo DeWitt, something far more modern lurks beneath his character.

An image of soup, which rockets Ego back to a moment in his childhood, is more than just a stroke of visual brilliance. His countenance may be that of a bygone era, but the nostalgia in his heart is unmistakably contemporary. Broken down to its origins, nostalgia is a kind of homesickness for the past, the distance of which becomes a kind of wound. Pale, out of shape, frequently bald, and almost exclusively male, the critic of our fictions is an adult baby lost in that wound.

Like Woody Allen’s typical film writer Allan in Play it Again Sam, Victor Tellez (Rafael Spregelburd) in The Film Critic is isolated by his own romantic idealism, prone to using the genres and clichés of films to frame his own life. The hyper-awareness of pop culture separates critic characters like Tellez and Allan from DeWitt. The apartment of Allan’s eponymous critic is plastered with movie posters, his own media-saturated childhood projected onto his walls. He was, like every generation after him, raised on television, on the omnipresence of films in constant rerun.

It only took a generation for the stuffed-shirt pedant of Eve to give way to the dweeb of Allan, but it’s an archetype that has changed little in the years since. It feeds on the implication that you’d have to be at least a little insecure to spend your whole life watching actors pretend to fall in love. But Allan’s post-psychoanalysis-era nebbish is still separated from today by 43 years. For all of his quirks, he is still professional, still urbane, an image of the film critic that would become ensconced in the public consciousness just a few years later with the televised pairing of Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert.

By sheer virtue of their weekly presence over 25 seasons (1975-1999), Siskel and Ebert gave a face to film criticism that bridged the demise of old Hollywood and the rise of internet film fandom. Their program underwent numerous rebrandings, but remained largely unchanged in format. Its combination of clips and commentary is still the basic model used by many online video reviewers. This format, and frequently the pair’s basic physical attributes, were endlessly re-circulated through parody and reference, from little-seen employee training programs for Blockbuster Video to sniveling caricatures in Roland Emmerich’s Godzilla (the real-life Siskel and Ebert were mostly just disappointed not to see their fictional counterparts at least get properly squashed).

So ubiquitous were their names that when Ron Howard made a two-headed monster for Willow, he half-affectionately named it the Eborsisk. Robert Townsend’s Hollywood Shuffle (1987) featured a send-up of ‘At the Movies’ called Sneaking in the Movies to spoof the habits of black audiences, typical roles reserved for African American actors and the self-proclaimed objectivity of the critic. The image of the high-profile, professional critic, equal parts passionate and irascible, supplied the spiritual antecedent for John Lovitz’s animated Jay Sherman, whose blatant physical flaws and disdain for pop culture met naked vulnerability and faux sophistication in The Critic. The show’s opening credits directly reference the New York skyline by way of Gershwin opening to Woody Allen’s Manhattan, while Siskel and Ebert voiced themselves in one episode as typically feuding soul mates.

But Siskel, Ebert—even Sherman, for all of his flaws—still paid the bills with their opinions. Sherman himself occupied a spacious Manhattan apartment on the salary of a televised personality. And, much as Allan somehow afforded a spacious apartment in 1972 San Francisco on a film writer’s salary, Tellez somehow affords a modern, urban lifestyle on nothing but the fumes of his own passion in The Film Critic. And maybe that’s realistic in Argentina, but the depiction of critics in fiction seems to assume an increasingly unbelievable financial stability. It’s interesting to speculate what a series called The Critic might look like today (professional riffing on the ubiquity of online fan reviewers is long overdue), but it’s unlikely it would open with establishing shots of Manhattan townhouses. The nostalgia in the hearts of Allan and Ego has become even more explicit, even as images of a professional critic has become out of step with the realities of earning a living as a writer in 2015. The splintering of media into countless self-identifying clans has made many of the old depictions of critics in fiction just as outdated as DeWitt. The reality of any given writer’s existence makes The Film Critic’s depiction seem quaint, but provides a dissonance that only proves the allure of the critic as a figure in narrative.

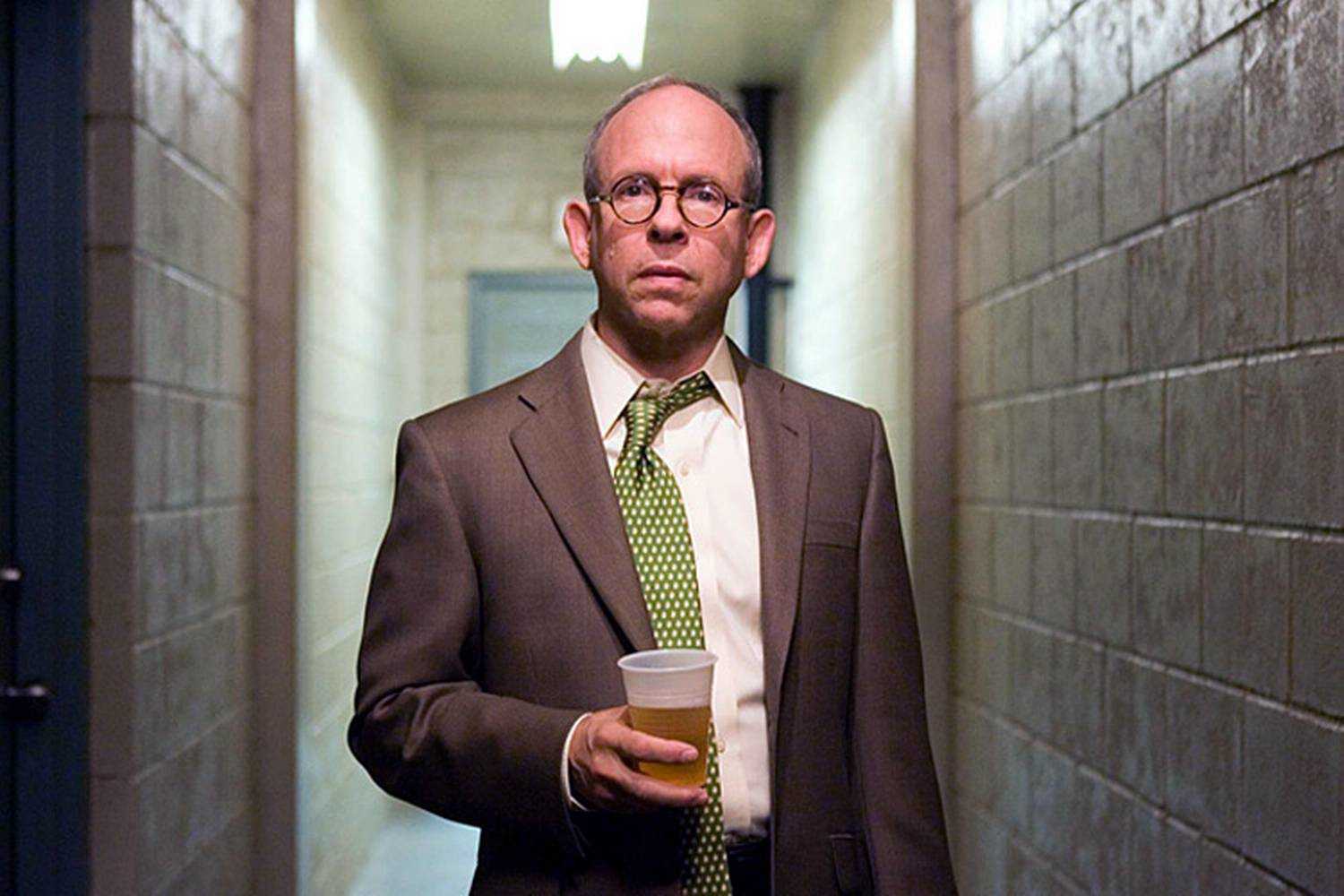

Long gone are the days when the National Catholic Office of Motion Pictures and Bosley Crowther could reach across the cultural aisle and influence the average moviegoer. But even when a relatively small media landscape meant that an endorsement from Pauline Kael could push a film that studios didn’t believe in—like Bonnie and Clyde or Last Tango in Paris—into the realm of audience interest, critical powers were limited. Classic as they may have become, nobody except old man Crowther praised The Sound of Music or Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, and yet both were essentially critic-proof, era game changers of massive commercial appeal just as baffling to critics then as the Transformers series is today. So in a sense, the idea of the critic as tastemaker has always been one that exists more commonly in concept than in execution. But it’s such a tempting concept that it continues to serve narrative schemes. Think of M. Night Shyamalan taking direct aim at his own detractors in Lady in the Water, siccing a CGI beastie on Bob Balaban’s dismissive critic. Shyamalan plays a misunderstood genius whose writing is destined to save the world. As if the decreasing returns of his films lay in the opinion of a single, powerful figure. Or look a few months back at the petulant theatre critic Tabitha Dickinson (Lindsay Duncan) in Birdman, who holds a negative review over Michael Keaton’s head like a sword above Damocles. She holds his life in her hands, this lone figure with her few inches of column space. Birdman takes place in the kind of universe where badly reviewed plays are never successful.

Even outside of isolated examples like these, studios still place huge faith in the opinions of critics as a whole. Still common is the practice of withholding early screenings for certain films from critics until their wide release out of fear of bad early press, though this typically applies to proven turkeys, Happy Madison vehicles, found-footage movies, and action movies released in February. Far more common are the muzzles placed on critics by studios for sneak-peek screenings of tent-pole pictures, allowing for weeks of cryptic Tweeting. This occurs despite the fact that many reviews of said tent-poles have acknowledged that reviews are meaningless, the audience’s decision to attend such films having been pre-determined beyond any merits of quality. It’s understandable. I could walk into a cinema and assess the aesthetics of a load-bearing beam, but its ability to hold up the building has nothing to worry about regarding my words.

A cynical view would see all of these as examples of cultural monolog, pre-determined audiences funneled into specific purchasing experiences through individually specialized combinations of content and advertising. Take this article for example. Is anyone not already invested in film culture and critical analysis going to read it? Why would they want to? In the end, however, the question of critical purpose is kind of an irrelevant one. Reviews affect some films and fail to affect others. One example from one era could contradict another. Charts could be invoked. The question is not how critics actually affect anyone, but what leads artists to deploy them as narrative devices.

In screenwriting, act follows act and beat flows into beat, aspiring to the symmetry of an atomic clock. For the vast majority of writers, the aspiration to achieve order in narrative (be it fictional, journalistic, or instructional) is all but totalitarian. Play it Again Sam has a scene where Allan encounters a nihilist, who compares a Jackson Pollack painting to “A tiny flame flickering in an immense void with nothing but waste, horror and degradation forming a useless straight jacket in a black absurd cosmos.” Some artists need to believe that chaos is lurking just around the corner, and that only through the structure of art may it be organized and set at bay. But both critic and artist often need to believe that their abilities are intertwined. A work’s value should be recognized, just as much as an informed critique of that work should be influential.

The alternative is perhaps too terrifying to imagine, a world without a rudder, taste with no tastemakers. A world much like our own, perhaps, in which Adam Sandler is a multi-millionaire and the most popular onscreen story is that of a dinosaur-robotic-military porn called Transformers. Maybe it all comes back to All About Eve, when DeWitt fights back when his power is questioned. He describes himself as a “Trappist monk” who has lived his life in the theater. “I’m somebody,” he proclaims. Just like any critic, real or imagined, he wants to believe that a life lived in service of art ultimately means something.