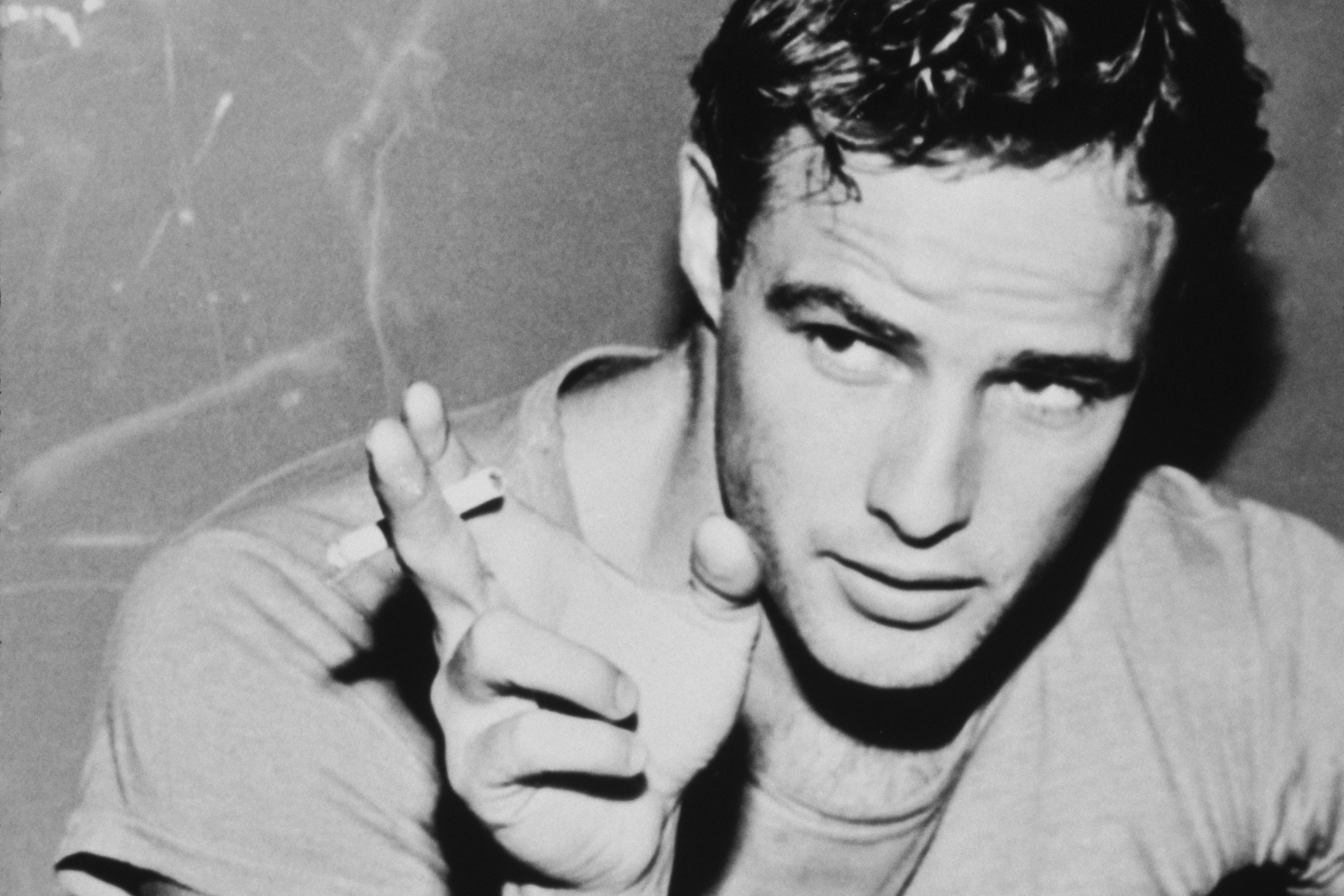

Was latter-day Marlon Brando the corpulent madman of myth, or a visionary genius who’d already moved on to the next level of movie acting? While the perception of the 20th century’s most famous actor as a paycheck-cashing recluse in his later years endures in the public consciousness, two recent documentaries cast a different light on the unraveling of the man who revolutionized cinema performance—and in turn expose a method to his supposed madness.

Released in theaters this week, Stevan Riley’s documentary Listen to Me Marlon provides an extraordinary glimpse into the inner machinations of Brando’s mind, culled from hours of audiotape that the actor recorded over the course of his life. Extracted from diary recordings, autobiographical monologues for a proposed documentary, and unusual self-hypnosis sessions that Brando laid down as his own therapist, the film composites an overview of the star’s career from his own testimony, crosscutting between different Brandos who ruminate on the various aspects of his life.

As a career profile, and one performed with the blessing of the Brando estate, it errs toward the conventional, disappointing given the richness of the material it had access to: We get Brando the white-hot Method juggernaut; Brando the bored movie star turned civil-rights crusader; Brando the Coppola comeback kid; and finally, Brando the besieged patriarch, contemptuous of his profession and happy to take studio money for mere days’ work. Listen to Me Marlon speeds to a halt in this latter period, addressing Brando’s grief at the incarceration of his son and subsequent death of his daughter but skimming over his scattered, though sporadically inspired, tail-end career performances.

What we do see, though, in a startling moment that opens the film, is Brando’s disembodied, digitized head, an electric blue visage reciting Macbeth’s “sound and fury” soliloquy that oscillates and fractures into pixels like a wireframe poltergeist. The sequence apparently comes from a 1980s software program that Brando, ever the patent dabbler, had invested in, allowing himself to be scanned into the machine so that his performance might be captured for future dwellers. Pretty soon, over those images, Brando muses on tape that cinema won’t need actors because it’ll have their digital avatars. Perhaps he simply saw an easy way to dispatch a hologram to do his next job’s bidding, but it’s more likely that the man who’d once upended cinema acting had his eye on the near horizon once again. And it’s this Brando that we hear too little about: the actor who, as Riley’s documentary reconciles, had reached an accord with the joys, however fleeting, of his industry, who ran near-mythical seminars like this, and whose supposedly bizarre turns in later life often brimmed with a wild inventiveness that has too long gone overlooked.

Where Listen to Me Marlon tapers off, another recent documentary acts as a useful complement to examining the peculiar vision of late-career Brando. Screened in a limited engagement last year and now widely accessible on Netflix, David Gregory’s Lost Soul: The Doomed Journey of Richard Stanley’s Island of Dr. Moreau captures Brando—anecdotally, at least—at the height of his speculated Hollywood contempt, a period in which he’d align himself with projects on an apparent whim and subsequently wreak production havoc like an adolescent prankster.

It’s the kind of film that delights in fanning the flames of the apocryphal “crazy Brando” legend. Widely considered a disaster, John Frankenheimer’s 1996 film The Island of Dr. Moreau had begun as a passion project for the hotly tipped, if erratically natured, young sci-fi auteur Stanley, who Brando had taken under his wing after the director impressed him with his pitch. Brando had identified a vision of sorts, but when Stanley ran afoul of producers and got himself removed the project, grizzled veteran Frankenheimer was brought in to salvage the film—and depending on how you look at it, Brando took it upon himself to either run gleefully amok or impose his own unique authorial stamp on the picture.

In all likelihood, it was a lot of both. According to New Line president Bob Shaye, Brando had sat down with Frankenheimer at one point to overhaul the script, having it rewritten so that Moreau would wear a hat for the entire film and that, in a final reveal, he would remove it to expose the truth that he was really a dolphin. “He’s fucking with them,” recalls Brando’s co-star Fairuza Balk, unable to shake her first glimpse of the actor emerging from his trailer wrapped in cheesecloth, slathered in white face paint and topped with dark sunglasses—a look, one production executive posits, that rendered him conveniently indistinguishable from his stand-in.

Lost Soul’s explicit agenda is, understandably enough, to trash Frankenheimer’s film and portray Brando, icon though he may have been, as a colossal pain in the ass. But its cheerful gawking overlooks the fact that so much of what is great about the strange final product can be traced directly to Brando’s influence—inspired, meddlesome, or simply a serendipitous fusion of the two approaches. As Listen to Me Marlon highlights, while Brando wasn’t averse to phoning in performances on what he deemed “silly” films at the expense of studio coffers, he was also deeply reflective and had a highly developed sense of empathy that manifest in unlikely ways. Occasionally, those seemingly conflicting impulses would converge in sparks of genius, and The Island of Dr. Moreau catches this contradictory Brando in all of his joyous flight.

In one of the film’s most unforgettable moments, Brando’s Moreau performs a piano duet with his diminutive doppelgänger, a creature rendered in prosthetic afterbirth flesh and dressed to resemble his master: tiny muumuu, bandana and all. According to Lost Soul, Brando had plucked the pint-sized Dominican actor Nelson de la Rosa (himself a celebrity in his home country) from a peripheral role in the cast and insisted he be elevated to a prominent “mini me” standing, convincing the production that his tiny discovery was going to be a huge star and the main attraction in the picture. Jest or no, even though the prediction didn’t come to pass, it’s tough to criticize Brando’s sincerity, or lack thereof, on the screen: the elephant-and-mouse chemistry between the two performers, such as it is, is mesmerizing, taking the scene’s prior off-kilter dynamic—Brando, rambling but with purpose, to his “family” of animal-human hybrids—and elevating it to something that’s both hilariously absurd and affectingly tender.

It’s the sort of next-level performance that would have been right at home in a Harmony Korine or Werner Herzog picture, possessed of a singular tone that’s neither specifically sincere nor satiric—and thus hard to place for those used to assigning criticism in the traditional parlance of performance assessment. Brando may have arrived at these moments via an impish desire to deflate the production, but the outcome was oddly dedicated. The uncanny empathy that the star brought to screen can be seen again in Lost Soul, where a crew member relays the tale of how Brando was so moved by the menagerie of beasts before him that he took the time to personally shake every hoof and paw—to the zany amusement of the teller, of course, who was oblivious to the genuine beauty to this behavior, a gesture that speaks volumes about the man’s sense of wonder and observation. (It’s worth noting, incidentally, that Brando’s antics appear to have rubbed off on his co-star Val Kilmer, whose oft-derided presence is actually something of a deranged tour de force; one wonders if Korine, who’d later employ him in his segment of the three-part omnibus film The Fourth Dimension, was a fan.)

That Brando’s unpredictable career path in his later life is frequently derided is no real surprise—there were times in which his legendary contempt for his employers invited it—but as both Listen to Me Marlon and, inadvertently, Lost Soul illustrate, there’s a level of complexity to his behavior that reveals a man very much exploring the odd crevasses of his craft. It’s easy to satirize an actor whose last couple of decades saw him use cue cards taped to his co-stars, teleprompters and radio earpieces to feed him lines, and just as easy to miss the work he was doing. Not unlike his close friend Michael Jackson, another visionary performer whose twilight years were fraught with public misperception, Brando was a genius in self-engineered exile—yet one who hadn’t lost his gift, merely transformed it while waiting for the world to catch up.

One thought on “Brando vs. Brando: Dueling Visions Of The Icon”

Pingback: Method and Madness: The Dueling Brandos of Listen to Me Marlon and Lost Soul | Luke Goodsell