It’s no secret that filmmakers love making movies about making movies. For some, that self-reflexivity is a sign of cultural and artistic myopia. For others, though, turning the camera back on the process of filmmaking illuminates the bonds between art and humanity. Mallory Andrews and Corey Atad sat down to talk about four such documentaries-about-movies from the slate at the 2015 Hot Docs Canadian International Documentary Festival. The first is Chuck Norris vs. Communism, which tells the story of the underground movement to bootleg American films in Romania during the Communist regime in the 1980s.

Corey: As far as movies about movies go, Chuck Norris vs. Communism is pretty typical in glorifying the role of cinema in culture and history. It’s more than a stretch to say that bootleg Hollywood movies on VHS brought about the fall of Communism in Romania, which does the film a disservice, since I do think it’s onto something very interesting about the value of an open culture in the face of oppression. It does help that the film has a genuinely interesting character in Irina Nistor, the woman who did the dubbing on most of the bootlegs, but I wish that the film’s attempts at being a thriller weren’t tied so closely to the political collapse of the Iron Curtain.

Mallory: This really felt like a movie that would have made for a really great short film, but stretched out to a feature both tries to take on too much, while also somehow treading the same ground over and over again. Irina Nistor’s story is the most interesting part of the movie, and I found myself wishing we’d have talked to her a little more than spending so much time with her younger reenacted counterpart. Which is a good segue into talking about the use of reenactments here. I’d say Chuck Norris vs. Communism is nearly 80% reenactments, which begs a different kind of evaluative criteria. Namely, are they worth it?

Corey: In a word, “no.” The film clearly takes inspiration from the likes of Man on Wire, where reenactments help make a doc into a genre film, but the problem goes back to the issue of substance. Instead of extrapolating on the themes and characters at hand, Chuck Norris vs. Communism continuously tries to force these “bigger” ideas that don’t fit. The film gets overloaded, and the talking heads feel like they’re spouting empty platitudes. Meanwhile, the reenactments end up coming across like a Band-Aid on a film that didn’t have enough to offer.

Mallory: It’s not that the reenactments are poorly made or executed, but to commit so much screen time to them, they have to reach for something beyond being merely illustrative. What new information do they reveal, what details do they call attention to? Why do we see the same images over and over again? This is a somewhat uncomfortable marriage between fictionalization and documentary, and for maybe the first time ever (while watching a documentary) I wondered: why not just make a straight fictionalized adaptation?

Corey: The sad answer is that it doesn’t have enough juice to be interesting at feature-length, regardless of how fictionalized it gets. But while we’re talking docs I wish had more to offer, Raiders! really let me down. It may be an unfair result of my antipathy toward the blind nostalgia that makes it okay for grown adults to spend tens of thousands of donated money to film a shittier shot-by-shot remake of a scene from Raiders of the Lost Ark. I’m not sure what it says about our current culture that we celebrate this urge to fulfill and capitalize upon every childhood whim. At the very least, I would have wanted to see more pushback against these guys from the doc itself, but instead when one of their old collaborators genuinely criticizes the project, the scene fades to black mid-sentence.

Mallory: I’ll have my say about the constant mid-sentence fades-to-black in a minute, but first I want to defend the project a bit. And by default, I guess I’ll end up defending nostalgia as a means by which to judge the things we like. I’m fine with my own sense of nostalgia driving my taste in movies, and I’m fully aware of how that nostalgia can be manipulated. With that in mind, I think Raiders! works not because of the shittier shot-by-shot remake itself, but what the process of making a shittier version represents. It’s youthful abandon, it’s DIY creativity, it’s about tapping into the childlike sense of wonder that made us love those things in the first place. On another level, it’s about how quickly those things that we cared so much about growing up quickly slip away when we take on more adult responsibilities—marriage, mortgage, kids, etc. In that way, I found parts of the film to be quite affecting, and overall I really enjoyed the movie. But that isn’t to say it is without flaws.

Corey: The slipping away of childhood is perhaps what I enjoyed most about Raiders!, particularly the falling out of the friendship and subsequent life disappointments. The disconnect for me was that their project to complete the final scene felt so at odds with that original DIY creativity. It’s not really them doing it with their own means anymore, which their old friend complains about. And their decision to approach it that way, and the way the documentary so supports their effort, is such a superficial way of trying to make the nostalgia of their childhood whole. It takes the creativity away and suggests that’s okay. I guess I just had a philosophical problem with the project and by extension the documentary.

Mallory: I had more of a problem with how the film was structured. There were numerous instances where the film faded to black in the middle of someone speaking, which leaves a very specific impression—like we’re supposed to think they’re talking too much. But many times, I wanted to hear what the person had to say! The worst was during an explanation of the ghost effects. It cuts just as Jayson is starting to describe how he used cloth on a stick in a water glass. If this segment was taking too long, I’d rather it just be cut. The fades were so distracting and borderline sloppy. However, sloppy editing was absolutely not a problem in Listen to Me Marlon.

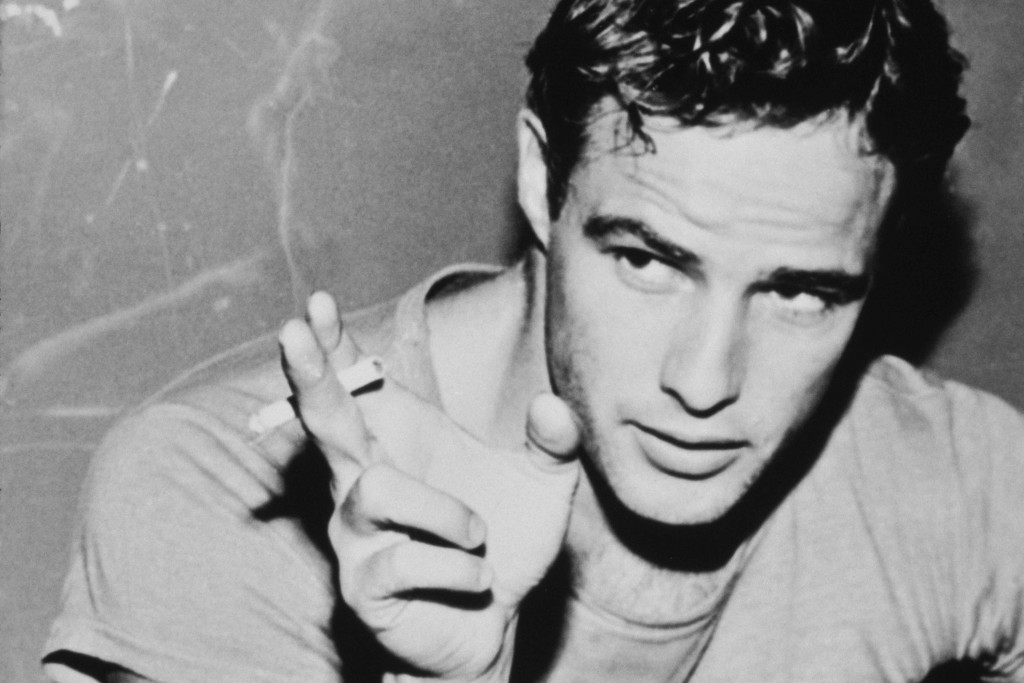

Corey: Totally. Listen to Me Marlon is basically a masterwork of editing and structure. It’s so refined, and the way it moves between scenes, and also between archival audiotapes is remarkable. In essence it’s not much more than a really good biographical portrait of Marlon Brando, at least structurally, but where the film shines is in its actual construction. The layering of Brando’s voice, talking openly about himself and his process, over footage from his films, and even these odd computer generated replicas of his face reciting Shakespeare, combine into a mesmerizing experience. And more than that, I found it incredibly honest about the process of acting, and of being a public figure.

Mallory: I loved it, and I’m usually not the biggest fan of biographical films. What really got me were the more existential textures. Brando’s body is gone and turned to dust, but he still exists as a filmic (and, thanks to his extensive audio recordings, a sonic) body. This is true of any film we watch, of course, as they become de facto time machines of the period and persons they’ve caught on camera. But Listen to Me Marlon really digs into that materiality, especially with the 3D scanned rendering of Brando’s face. This was a gimmick that could have fallen flat on its face with how silly it might have been—but for me it was totally effective. Brando lives!

Corey: And at the same time that he lives, he also haunts. Brando doesn’t quite appear fully formed; he’s more like an apparition, bestowing his feeling and knowledge and wisdom unto us. It might sound like a cliché to say that Listen to Me Marlon is about mortality itself, but that’s exactly what it’s about. It’s about living and the impermanence of life, and it’s about having an impact in life and that impact remaining in vivid shadows even after death. I love when a documentary lets me chew on themes like that, and I never would’ve expected it from an insider-y bio of a Hollywood star.

Mallory: And the thing is, we still get that insider-y Hollywood stuff. The film revisits the memorable moments—his deferral of his Academy Award in protest against the US government’s treatment of First Nation citizens perhaps being the most famous. But by overlaying it with Brando’s constant narration, it recasts these tentpole events in a new light. It was mesmerizing, and I can’t wait to revisit it. I was far less enthused by the recasting of filmic events in The Wolfpack, however.

Corey: We definitely disagree on this one. I thought The Wolfpack was near-great. “Near,” only because I think the film loses steam at a certain point, and never finds quite the right note to land on. That said, the relationship to film in The Wolfpack is so interesting. It’s not about nostalgia, or even film as a capture medium for memories or events. Instead, what’s explored is the way we relate to the world through movies. Here, you’ve got a set of brothers who have almost no real exposure to the world outside their New York City apartment—the result of the abusive, cult-like philosophies of their father—and yet they’re able to understand and mimic normal human interaction primarily through what they’ve seen in films.

Mallory: I still very much enjoyed the film for what it was: a solid representation of a fascinating news story. But as a piece of craft, it just didn’t do it for me. As you say, it loses steam after a certain point. It starts at one level, and sort of stays there, with little forward momentum to sustain interest. I wasn’t satisfied with the parents’ explanation of why they kept their children sequestered, and it really felt like the filmmaker’s relationship with the family hinged on her very gentle treatment of them, so she didn’t push the matter. Which isn’t inherently a bad thing, of course. It just is what it is.

Corey: This was clearly a case where the filmmaker was risking access if she became antagonistic, but insofar as the film is about the kids’ experience and not the parents, I was satisfied. I loved the way their father is almost an evil presence who is barely seen in the first half, and then once he’s revealed, he’s kind of just a sick, drunk loser. Their mother was interesting in the way she seemed almost as abused as the kids were. And bringing it back to movies, the way that cinema—even the likes of The Dark Knight Rises—can be a mode of both escape and learning really got to me. And if we’re to compare it to Raiders!, here we have kids for whom the escape into recreating movies shot-by-shot is a much more meaningful expression of creativity, at least to me.

Mallory: But I don’t think the film really digs into the significance of living your life through movies. It sort of stays on the same level as Raiders! in that respect, celebrating the creativity (that Batman costume was AMAZING), but not giving a full sense of the sociological and psychological ramifications. The Wolfpack may not be about the parents, but their decisions have directly impacted the lives of their children, so I don’t think it’s too much to expect a little more from them. The kids themselves are completely charming and disarming, and I thoroughly enjoyed spending time with them. But I was left with unanswered questions.