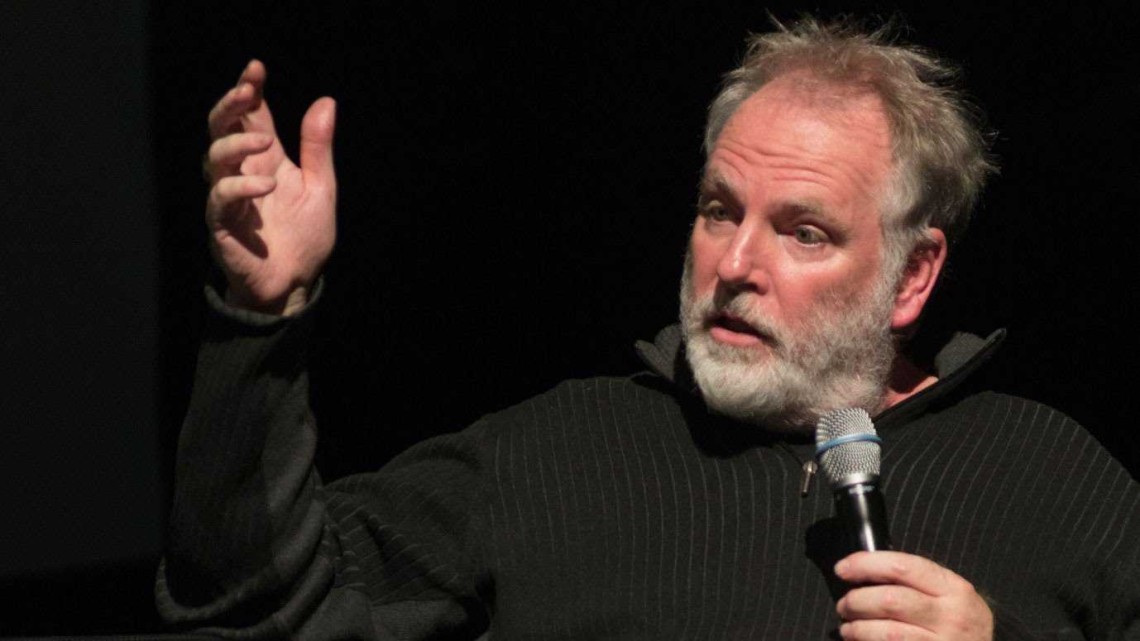

On July 19, as part of its summer series, TIFF Bell Lightbox in Toronto feted experimental Canadian filmmaker Guy Maddin by hosting a free screening of his 2007 phantasmagorical quasi-memoir My Winnipeg, followed by a Q&A with the filmmaker himself. Movie Mezzanine had the opportunity to speak via email with Maddin about this occasion and his feelings on the state of cinema. The interview centers on Maddin’s past works, and brings to light his reflections on the dichotomy of nostalgia and postmodernism, often relating his theory of melodrama and its implications for My Winnipeg. A survey of introspection is the most apt way to celebrate this inward-focused, memory-triggering film. Furthermore, Maddin mentions his favorite filmmakers, his films he’s most proud of, and technology’s involvement in cinema.

MOVIE MEZZANINE

You argue that everyone is manipulated into acting a certain way and that as long as they are aware of it, that’s great, which is an argument you have used to defend melodrama. Given this, why did you not use melodrama as a style for My Winnipeg? Was it because of the political nature of the work? I mean that you wanted to talk about city development, its history, and politics, and so you felt it necessary to use a documentary style since audiences, rightly or wrongly, see it as a more authentic way of representing reality.

GUY MADDIN

The instant I thought of My Winnipeg, its tone was set in my head. I love my city, and yet it exasperates the hell out of me too, so I knew I needed to establish the real Winnipeg first, supply more grounded descriptions of the dump, if only to rail against this literal-minded approach all the more bitterly later. I had to be more disciplined than usual in accounting for this unlikely populace, I had to describe something real, the better to take it down. I could just construct melodramatic fantasias and then complain about them. What a self-canceling exercise that would have been! I’ve only recently watched Thom Andersen’s Los Angeles Plays Itself, made just a few years before my picture, and was struck by how similar in tone Anderson’s voice-over is to mine—the same grouchy spite-love. (Though Andersen wrote without the self-pity that threatens to scuttle anything I touch.) I think I indulged my inclination for melodrama whenever I happened to deliver a paean to my hometown.

During my more positive, and sometimes even rapturous, passages about Winnipeg, I used melodrama for what it does best. It reveals the truth by disinhibiting itself: less repression, less decorous concealment, and more naked truth, more emotional that objective facts, stuff blurted straight from the heart, straight from unreliable memory. Let’s face it, sometimes the facts must be represented by something more beautiful than the slow march past of mere historical incident. A filmmaker can do him or herself a favor by packing incident into something more like a big Pride Parade, an exultant orgy of ecstatic truth seen in one intoxicating rainbow ribbon. The movie is only 75 minutes long and it’s a documentary about the way I feel. It’s not about the civic demographics, growth indexes and tertiary industries of a Midwestern town. I never felt I shortchanged myself in the melodrama department while making this movie. I used all the same old strategies used in my fictions, only I applied the disinhibiting strategies of melodrama to history instead of mere story.

MOVIE MEZZANINE

Are you nostalgic for the past?

GUY MADDIN

My mother has severe memory impairment, a dementia that leaves her without a past. She lives in a perpetual present. As a result, she has no idea where she is, and no idea how she got there. Her perpetual present is a pretty shrunken thing. The impairment is utterly disorienting, confusing, and yet soothing for her—it’s an anesthetic—since she is left completely comfortable at the end of a long life of agonizing sadness and various euphorias, all forgotten. A city without some sense of its past is just as demented. It may be comfortable in its pastless present, but what an impoverished present. About its future, I will not even speculate: Can a city just wander outside someday, when no one is watching the door, wearing nothing but its nightie and slippers, and get lost forever in a euthanizing snowstorm?

MOVIE MEZZANINE

You have always shown hostility to being called a postmodern artist. Why is this? What aspects of postmodern culture contradict your work? Is your rejection due to not wanting to be seen from a specific philosophical perspective, a sort of reductionist approach?

GUY MADDIN

I think I’d be a happy post-modernist now, after my ’80s discomfort with that term. I now realize emotions can be exhumed and animated by the postmodern touch. I once assumed they could not. I hope people see my stuff, if they see it at all, as some kind of smoothie featuring po-mo, modernist, and even romantic flavors. Now with a new Whipped Internetty Topping!

MOVIE MEZZANINE

In your work, there is a tension between romantic excess and absurdist humor. How does this contradiction fit with your theory of melodrama? I ask this because usually in melodrama we are looking for the moments of becoming, but in your work this tension means there is constant emotional change.

GUY MADDIN

Well, don’t forget that my working definition of melodrama involves an embarrassing level of uninhibited truth. Some truths are so lugubrious, my inner showman can sense the audience’s growing suspicion I might be taking myself too seriously, so in a pre-emptive strike I sabotage my dignity with something from my arsenal of cinematic whoopee cushions. I don’t think my understanding of melodrama is sophisticated enough to allow recognition of any moments of becoming. I just put myself in a Tourette’s trance and let ’er rip, see what happens. The result is my modus operandi. As a result of my primitive understanding of basic script dynamics, I’ve probably destroyed any hope for an accumulated emotional payoff in movies that are frequently of extreme emotional importance to me.

MOVIE MEZZANINE

I am always amazed by the high degree of intellectualism involved in your work. Of course, watching your movies is not like reading a philosophical book, but at the same time, your work provides moments of deep reflection on human nature. Cinematic images in this sense are like the “concepts” in philosophy, if we want to refer to Deleuze. Given this, I was quite shocked when I realized that you have said that film and philosophy do not always mix so easily. Can you elaborate on that? Do you not feel that being funny and worldly, to embrace the Dionysian aspects of life, could be seen as the part of the philosophical tradition in the West, at least from a Nietzschean perspective?

GUY MADDIN

I completely agree with you, though I admit this is the first I’ve thought about my stuff in this light. Thanks, I feel better now about what I’ve been doing all along!

MOVIE MEZZANINE

It is very easy to relate some of your movies to Freudian and other psychoanalytic concepts. For example, there is a quality of confession involved in your work which can be seen in the emotional attitudes your characters have towards their parents, and the parents’ actions towards their children. However, at the same time, there is also a playful quality involved in your work. Your characters enjoy doing crazy things and are beyond any source of rationality in this sense. This quality of playfulness is part of your cinematic power. So given this, how do you feel about psychoanalytic readings of your work? What do you mean when you say that cinema is therapy for you?

GUY MADDIN

If someone attempted a psychoanalytic study of something I made, I would be honored. Every now and then, something like this is attempted. The writer Wayne Koestenbaum recently speculated that the existence in My Winnipeg of the locally broadcast Winnipeg TV show Ledge Man—which every day for 15 minutes features a man crawling out on a window ledge to threaten a leap, only to be cajoled back from suicide by his mother, day after day, every day—is actually an attempt on my part to indefinitely postpone the suicide of my brother that really happened back in my early childhood. When I read Koestenbaum’s speculation, I immediately felt he was right. Though I had never known why I put Ledge Man in My Winnipeg, Wayne Koestenbaum figured out why. I was so shocked to discover this in his words, during that instant, I felt my knees buckle beneath me and a little sob escape my bosom. Though this is not the kind of therapy I seek when making films; in fact, I don’t even seek it at all. It just happens when a filmmaker takes something emotionally obsessive for his subject matter.

Filmmaking forces the haunted director to convert his demons into a script, a budget, and casting call, production design and shooting schedule. The filmmaker lives with his most personal memories in their new form for at least a year, maybe longer, while they are converted from raw emotion into facsimiles of emotion viewable on screen. Everything, no matter how precious and powerful it may have once been, is simply converted to work units during film production, and the long process of making the film makes sure that the new versions of memory replace the older and truer versions, sucks all the flavor out of them, until one is no longer obsessed with a past episode but made weary of it. Having to discuss it during Q&As and interviews increases the weariness. One is cured of countless pathologies through filmmaking’s highly repetitive boredom therapies.

MOVIE MEZZANINE

The plot of Careful (1992) has the theme of a divide between masculine and feminine, with males and females being terrified of each other. At the end of My Winnipeg, you argue that the city could be different if women controlled it. You have also defended melodrama in previous interviews based on the argument that this genre has been rejected by patriarchal culture. Your work definitely makes women and their imaginations and desires central. In what way have you tried to incorporate women’s gaze, dreams, and wants into your work?

GUY MADDIN

I feel embarrassed that my movies have been almost entirely phallo-centric till now. But I’m so sick of my place in patriarchy, and patriarchy in general. I long for matriarchy, not because I’m a mama’s boy—which I protest I am not, all the while being careful not to protest too much—but because we simply must try something new. The patriarchal system is a disaster, utterly. I hope to spend the rest of my career doing my bit for the revolution. If I can pull it off without feeling fake, I shall attempt to adopt a female gaze from now on, if not for an entire film’s point of view, then at least for its female characters. But if I feel I don’t know what I’m doing, I’ll default to using as characters my usual male control freaks, cowards and goofuses. I really love, by the way, the work of Amy Schumer on Comedy Central. Also on the same network, those geniuses Ilana Glazer and Abbi Jacobson on Broad City! They really flip the male gaze completely. It seems these three women alone will destroy patriarchy if their series are simply renewed for another couple seasons, and do so with their hands tied behind their backs.

MOVIE MEZZANINE

There is a high degree of eroticism in your work, and the way that you represent sexual tension is not only limited to the conventional approach of depicting sex scenes, as in mainstream movies. Through a variety of unexpected and undefined ways, non-formalized practices, and even sublime fetishism, the images of your movies represent sexuality. Sexual energy is constant in this way and is like an unstoppable river, a tornado that could include and touch everything; in this sense, it should be called eros in the way that Marcuse defines the term. Can you elaborate on this aspect of your work?

GUY MADDIN

I guess I’m one of those filmmakers who, at the start of my career, was driven by sheer boner power to make movies. I would say most people in movies start this way, with an irrepressible desire to project themselves into the world somehow, to penetrate the world and inseminate it with their bright ideas and charisma, as if these things, which are usually the gas and sassitude of youth, were genuinely genome-encoded qualities the world would be lucky to receive. Bless the world’s horny youth armed with cameras. I still feel like I belong in their ranks, even if I am now the creaky old vet slumped over to one side with a banged-up bugle resting on his dozing chest.

MOVIE MEZZANINE

You have shown a deep interest in cinematic experimentation, and unlike many filmmakers, you constantly work with short films and music videos in order to experiment with new cinematic reality. Given this, one of your concerns is the representation of fiction, which one might call bringing back the Lumières’ animation quality in the cinema. So how do you feel about digital technology? I ask because digital provides new possibilities for experimenting with fictional images, which you can easily create in your computer. Did you try to experiment with digital? If yes, how did you feel about these experiments compared with the possibilities that film provided for you in the past?

GUY MADDIN

I work only in digital now. Digital possesses everything I love about film, except the smell of a freshly opened can of stock, and so much more. I can do everything I wanted to do on film, do it faster, cheaper, and better—for my purposes—in digital. I know Quentin Tarantino and Paul Thomas Anderson are sticking to emulsions, and even going 70mm, and I’m so glad they are, but I’m even more glad I’m not. I can’t afford to stay in film, and my aesthetic has always been about making stuff at the hoi polloi level of affordability. I’m concentrating all my hopes, now that movies can be shot and edited for next to nothing on consumer-brand technology, that the medium will finally produce its Rimbaud, its first 16-year-old poetic genius. That’s what I’m excited about.

MOVIE MEZZANINE

You have talked a lot about your favorite silent films, but do you have any favorite international contemporary films that you find on par with or even more deranged or absurd than your own work? What about a Canadian feature?

GUY MADDIN

I’m always excited to hear if there is new work coming soon from Alexander Sokurov, Roy Andersson, Martin Arnold, Lisandro Alonso, Miguel Gomes, Rick Alverson, Mathias Muller and Christophe Girardet, Gregg Turkington, Tim Heidecker, Eric Wareheim, or Derrick Beckles. But wait, you said “deranged or absurd.” These folks are just plain great—and some of them work mostly in television or online.

MOVIE MEZZANINE

At this point in your career, which of your films are you most proud of and why? Is there any movie that you might change if you could travel into the past?

GUY MADDIN

Of course I’d change them all. Almost all of them are too long, or too inept at getting across to the viewer why I wanted to make the things in the first place. I guess my two favorite films from the past are Archangel (1990) and Cowards Bend the Knee (2003). I actually had fun making them, and they turned out almost exactly as I has always hoped. If only more projects could be like those. Of course, they were incredibly unpopular. I wish I could trick people into watching them somehow. Archangel was maybe my biggest commercial flop, and that’s a flop in a career utterly unconcerned with commercial success. It’s a flop’s flop! I’ve decided I must write a novelization of Archangel: my least admired movie transposed to the least respected medium, the novelization. Now that’s a career move I need to make!

MOVIE MEZZANINE

Are you currently working on a new project?

GUY MADDIN

Yes, I am writing my next feature script with Evan Johnson, my co-director. It’s about a country in trouble.

One thought on ““A Happy Post-Modernist Now”: An Interview with Guy Maddin”

Pingback: Guy Maddin Answers Some Email « Movie City News