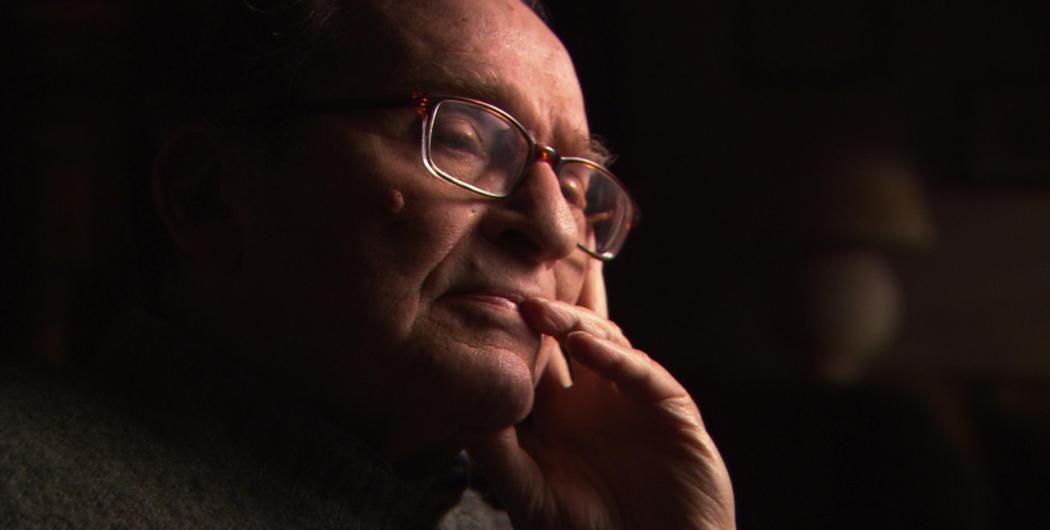

A modest speaker despite his 50-year career, Sidney Lumet was never one to overstate his role as an auteur. In an extensive interview by David Anker, edited by Nancy Buirski into a new episode of the American Masters series, Lumet reveals his insights into filmmaking and the biographical events that might have shaped his artistic interest (“vision” is a term he takes the time to dismiss). Efficient and versatile, delivering films on schedule and usually under budget, Lumet left behind a filmography that amply extends past the ’70s peaks of Serpico, Dog Day Afternoon and Network. It takes a fairly different set of epithets to praise 12 Angry Men, Long Day’s Journey Into Night, The Hill and Prince of the City.

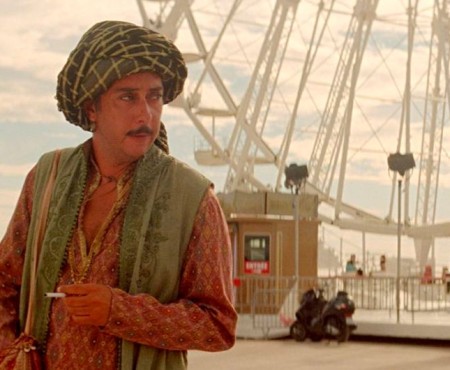

Buirski’s compression of Lumet’s life and career is therefore honorable for being thorough. It usually takes no more than two or three clips per film to connect the dots in Lumet’s self-evaluation, and to make the documentary a coherent and appetizing introduction to his films. It’s even accurate enough to chronicle the “lucky” ascendancy of his career and give credit to his collaborators: Henry Fonda for having accepted the lead of his first feature 12 Angry Men; Paddy Chayefsky for the mad-as-hell screenplay of Network; Al Pacino for being the “bleeding wound” that would bring humanity to Dog Day Afternoon.

Whether he talks or not of the motivations behind his guidance (for instance, his decision to adopt a naturalistic/unembellished look with the camerawork of Dog Day Afternoon), Lumet always presents filmmaking as a down-to-earth entrepreneurial process which goes right – as he put it in his book Making Movies – when everyone involved is making the same film.

It’s always been tricky to discuss Lumet films thematically, since it smoothes out the often significant differences in complexity and aesthetic value between them. Buirski’s zeal is most questionable when she associates father-son sequences across Lumet’s career (Daniel; Running on Empty; Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead). This is especially noticeable when she decides to interrupt a biographical passage about Baruch Lumet’s life as an actor with a monologue performed by Ralph Richardson from Long Day’s Journey Into Night, having the actor-father character of James Tyrone ostensibly complete an undocumented passage from the Lumet family history.

Another occasionally tiresome tendency is to choose the most dramatically charged scenes of several films to “prove” Lumet’s skill with actors. While this type of editing makes it obvious in a few seconds that the likes of Katharine Hepburn, Marlon Brando, Anna Magnani and Philip Seymour Hoffman gave it their all while working with Lumet, it also gives off a limited idea of good acting. This is especially at odds with Lumet’s statement in the documentary that Method acting is only one type of performance and isn’t inherently more valuable than various other traditions.

Lumet is more prone to talk about films pragmatically. He says that his goal when working isn’t to send a message, but to tell a certain story with certain people and, if it’s done well, the message might come across. It’s to Buirski’s credit that, in editing the interview, she goes further in pursuing his influences in moral and political matters and how they come to structure his films. On Prince of the City, Lumet claims that he had initially distanced himself from the character (because, where he comes from, “a snitch is a snitch”) and that it was only when watching the first cut of the film that he knew where he stood.

Buirski’s documentary doesn’t set out to engage in the critical debate around Lumet’s film. Nor does it attempt to negotiate his rank in the American film canon. Although he’s wary with moral verdicts, Lumet’s ambivalence toward social structures that comes across in Network or Serpico is ultimately held in check by his almost sentimental belief in human integrity. The wariness toward court procedures in 12 Angry Men is still a lot milder and closer to classical norms than, say, Otto Preminger’s thoroughly skeptical Anatomy of a Murder. The portrait painted in By Sidney Lumet that of a humane figure, whose ability to work with people was a large part of his artistic merit.

Two stars out of four.