Director Adam McKay’s jump from some of the most notorious bro comedies of the millennia (Anchorman, Talladega Nights) to The Big Short, a film about the global economic recession, might seem extreme even to discerning moviegoers. But those familiar with McKay’s 2010 comedy The Other Guys might have been able to tell. There is, for one thing, that rather didactic end-credits animation sequence explaining big financial concepts vaguely discussed in the narrative. But the premonitions run deeper.

As early as 2011, sociologists Jeff Kinkle and Albert Toscano performed an early assessment of the American cinema’s response to the economic downturn. Their piece “Filming the Crisis: A Survey,” published in Film Quarterly, included The Other Guys alongside other films about the recession, including Up in the Air, The Company Men, and Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps. Kinkle and Toscano noted that McKay’s film was of particular interest because, overtly, it bears little resemblance to the other aforementioned films.

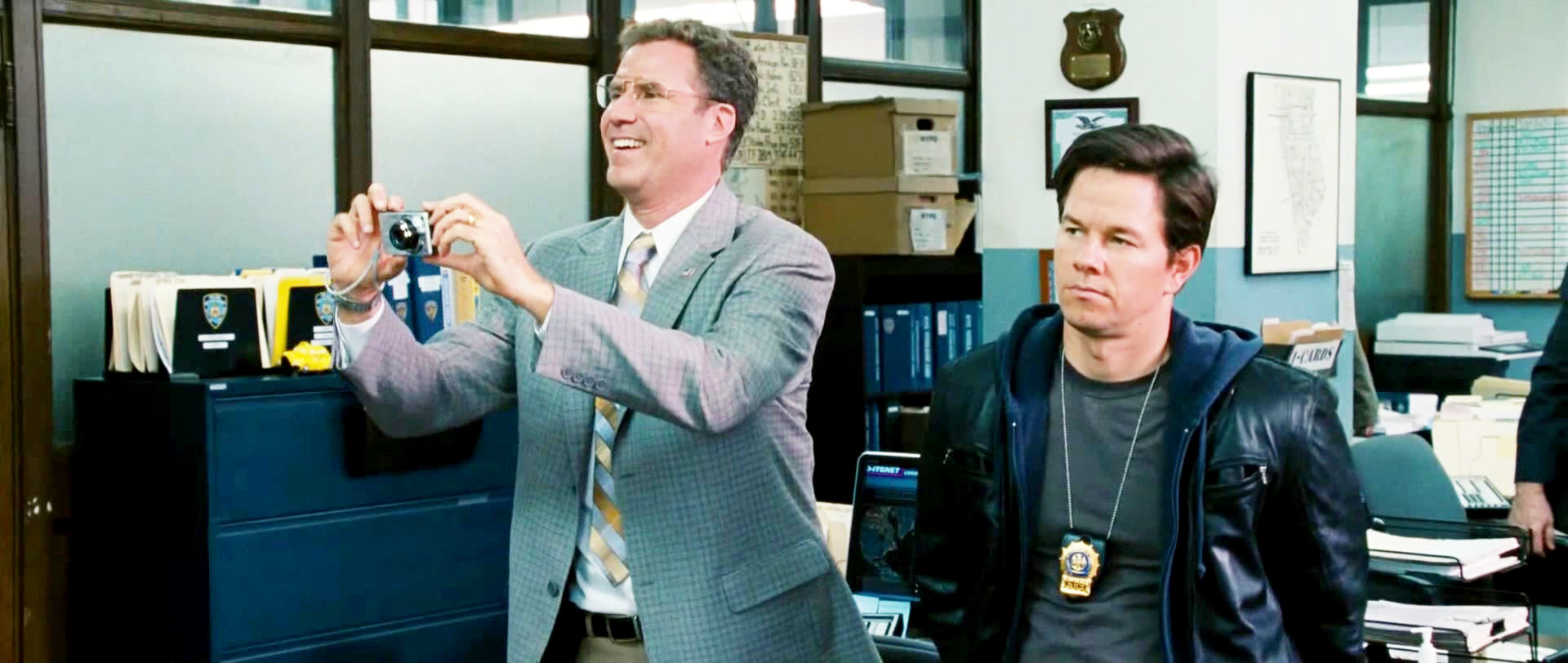

The Other Guys is, through and through, a buddy-cop action film. The dynamics of the American economy always come second to the dynamics between the two comedic leads, paper-pusher Allen Gamble (Will Ferrell) and hot-headed Terry Hoitz (Mark Wahlberg), who are teamed up when Terry is relegated to desk duty after accidentally shooting local hero Derek Jeter. In many ways, the inciting incident that gets the plot rolling is not unlike the many revelatory moments for the protagonists of The Big Short: finding countless instances of Wall Street’s fraud that would eventually affect the American taxpayer.

Except that in the case of The Other Guys, it might be more accurate to describe Allen and Terry’s discovery as something they stumbled upon rather than found. Like the modern-day equivalent of nabbing Al Capone on tax fraud, the duo arrests Gordon Gekko caricature David Ershon (Steve Coogan) over a building-permit issue and are unwittingly led to defraud their police department out of their pensions. Right before the film’s climactic moment, the officers’ money man (who Allen and Terry ever-so-quietly shoo out of the room earlier in the proceedings) tries to explain just what he sees in Ershon’s financial plans and how he intends to help the hard-working cops by reinvesting their fund—only to be abruptly cut off by a shoot-out.

This is McKay’s approach throughout The Other Guys: introduce an issue within the narrative, then cut it off with a comedic or action-genre trope. The financial crisis is never fully explored as a social milieu, instead taking a backseat to a punchline or a guns-ablaze set piece. Case in point: A police captain played by Michael Keaton has to moonlight at Bed, Bath & Beyond—a sad observation on the state of the American economy, but McKay never gives his audience to reflect on it. Instead, he goes for a cheap laugh by having Keaton’s Gene Mauch add that he does it so he “can put my kid through NYU so he can explore his bisexuality and become a DJ.”

McKay’s approach with The Other Guys is really not much of an anomaly in the American cinema’s response to the economic collapse of 2008. Some of the more fascinating, if not entirely successful, films to grapple with questions arising from the crisis came embedded within traditional narrative structures. Andrew Dominik told a proxy narrative about the financial system’s criminality through a gangster flick in Killing Them Softly (2012). Woody Allen restaged A Streetcar Named Desire in Blue Jasmine (2013) to ponder Bernie Madoff’s crimes. Brett Ratner’s Tower Heist (2011) addressed Madoff’s Ponzi scheme but found hokey retribution in a heist caper.

But the vast majority of cinematic responses kept in the same cartoon Wall Street villain seen in The Other Guys, and swapped out the cartoonish heroes for embattled yet woodenly virtuous ones. From real-life unemployed people interviewed in Jason Reitman’s Up in the Air (2009), to the upper-middle-class men suffering underemployment in The Company Men (2010), and even the wannabe Jimmy Stewarts of Larry Crowne (2011), the average Joe is consistently framed as the victim. Furthermore, films like Win Win (2011) and At Any Price (2013) depict in heartbreaking fashion the ways that the economic crunch forces these salt-of-the-earth Americans to forsake their decency.

Their adversaries are mostly ridiculous members of the upper crust, be it the boastful financiers of Margin Call (2011) who compare their salaries on the brink of economic Armageddon, or Richard Gere’s hedge-fund magnate in Arbitrage (2012), who finds himself drawn to increasingly desperate measures to ensure the sale of his business. Perhaps most egregious of the bunch is Oliver Stone dragging Gordon Gekko out of mothballs for Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps (2010), cashing in on the latest recession with nothing new to say, save a few corny lines like, “Money is jealous, and if you don’t pay close attention, you’ll wake up in the morning and find she’s gone forever.”

To be fair, Stone at least takes a pass at addressing the changes on Wall Street over two decades. When lecturing a crowd, Gekko states, “Someone reminded me I once said ‘greed is good.’ Now it seems it’s legal. Because everyone is drinking the same Kool-Aid.” Yet for all his talk of market-level failures, no one would ever be able to tell from the movies coming out at the time. Most depictions of bankers fall into the “bad apples” category—rotten products of the culture, but not necessarily indicative of a deeper corrosion. In essence, characters like The Other Guys’ David Ershon help maintain trust in the system producing such malefactors by deflecting attention away from it.

But in 2015, with unemployment stabilized and the economic outlook fair enough that the Federal Reserve just raised its benchmark interest rate for the first time in almost a decade, American filmmakers are gaining the clarity that comes with retrospection. This year has seen the release of two films that finally identify the key problems in the financial system as institutional, not individual: Ramin Bahrani’s 99 Homes and The Big Short. Neither film has any pretenses of being about anything other than the crisis, but only McKay’s enters into dialogue with the films that preceded it. In The Big Short, one can find both a distillation of the challenges that intimidated American filmmakers in approaching the Great Recession as well as a significant maturation of style illustrating how to overcome such obstacles.

Rather than shying away from the complexities of the financial products that led to the overvaluation of the housing market, McKay and screenwriter Charles Randolph dive right in. When scenes rely on knowledge of a derivative, they do not attempt to weave in a line or two of expository dialogue to clue in the audience. Instead, they often trot out celebrities to explain a term in metaphors or common parlance—or just have Margot Robbie seductively defining subprime mortgages while sipping champagne in a bubble bath. These moments find a middle ground between the distancing effect of Bertolt Brecht’s epic theater and the cutaway gags in Family Guy. McKay supplies his audience with the laughs they want while also providing the information they need.

Contextualizing these intricate financial products within the context of humor makes them seem more intelligible. It also gives McKay more freedom to insert his personal commentary. He’s not above the heavy-handed instruction from Ryan Gosling’s narrator, Jared Vennett, who often instructs the audience on when they need to pay attention and what they should consider as important. Nor can he resist obvious imagery, such as Melissa Leo’s rating agent afflicted by temporary blindness after getting her eyes dilated.

Yet as burlesqued as these aspects may seem, are they any more ridiculous than the system of institutionalized hubris and fraud he takes such pains to depict? The hubris of the mortgage market to take massive risks predicated on the assumption that housing prices would rise for eternity is risible, like a page pulled from a satirical script. McKay pulls out all the stops to make sure that comes through, and if that means he has to introduce a securities convention in Las Vegas with the haunting overture from The Phantom of the Opera, so be it.

Humor trivializes the issues in The Other Guys. In The Big Short, it is employed to illustrate just the absurdity of the system, and then it amplifies our incredulity at that absurdity once the bubble bursts and nothing is funny any longer. By embracing the spirit of his inner comedian, McKay discovers an intrepid streak that extends beyond one-liners and seeps into the presentation of the tricky material. The Big Short thus not only supersedes all his prior work but also could very well mark the first fully informed fictional film on the financial crisis to date.