In August, 1965, the Los Angeles neighborhoods of Watts and Compton caught fire. After years of racial tension, segregated housing and police brutality, the largely African American community had rioted. Surviving footage shows flames, rubble, devastation. But there are no faces. The only people visible are the National Guard and the police. A few residents flit by the camera, out of focus and seemingly unimportant. This is an event of numbers, seen from aerial views, history as determined by dates and statistics. But twenty-one year old Charles Burnett would have only had to look outside to see the rubble forming, and there would have been faces everywhere. Over the next decade, the images of Blaxploitation filled in the gap left by those absent Watt’s faces and left little room around its edges for anything otherwise. But Burnett was about to become a filmmaker himself. And his future contemporaries would soon converge at UCLA, hungry to speak the truths of absent faces.

In the 1970’s, the popular narrative of African Americans onscreen was relegated to the narrow confines of Blaxploitation. It told audiences that black women looked like this:

Here is the woman now more synonymous with the era’s black cinema than any other actress. Pam Grier is defiant while still fashionable, angry while still typically feminine. But in 1977, Burnett filmed faces that looked like this:

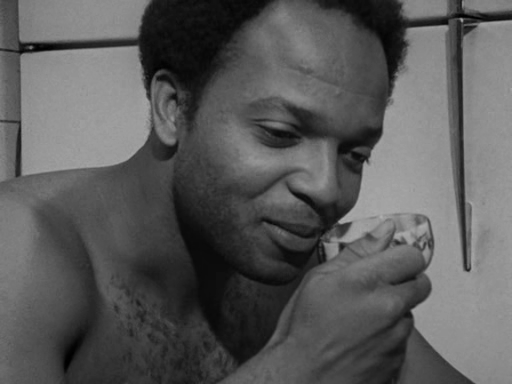

The film was Killer of Sheep. It took a neorealist approach to the Watt’s neighborhood, revealing the continued effects of economic and physical devastation. The film follows a family through a series of vignettes, revealing the texture and rhythms of life for their impoverished community. In a decade in which black malehood was portrayed as violent and aggressive, here is very different kind of face:

The man places a teacup gently against his cheek. He says it reminds him of making love. Here is gentleness, it says. Later, the man and woman appear together as they slow dance in their living room. It was an era that saw filmmakers consistently exploit the black female body and reduce black male sexuality to a threatening specter. But here is a scene brimming with authentic intimacy and eroticism:

The neighborhoods where the film was shot were only twenty miles from UCLA, but in 1969 a student was more likely to learn about the rubble films of Germany than be exposed to the destruction still left over by the riots. In January of that year, two black students had been shot dead on campus after an alleged altercation over the leadership of the Black Studies Program. In September, the UC board of regents dismissed philosophy professor Angela Davis for her Communist affiliations and “inflammatory language”. So the same month as Davis’ ousting, pressure from the growing ranks of students of color, Burnett among them, led to the creation of the UCLA Ethnic Studies Center, focused on the study of African, Asian, Chicano and Native American culture. The ensuing wave of creative output by students of color would go on to become known as the LA Rebellion.

Watts’ lingering psychological scars bleeds through in the images of Killer of Sheep. But there were wounds everywhere. Haile Gerima had emigrated to the US from Ethiopia in 1968. His student work at UCLA revealed a deep connection with the inner struggles of African Americans. But he would return to Ethiopia in 1976. There, he found and filmed women like this’:

The film is Harvest: 3000 Years. The wound is the impact of neocolonialism, Ethiopia struggling for its soul after the departure of the Italian government. Like the Senegalese filmmakers who influenced him, Haile used film to tell the story of Africa’s struggle for post colonial identity. Like Killer of Sheep, Harvest is nearly plotless. A rich land owner abuses his rural workers. He has stolen land from another man, who has since gone mad. Haile uses the landscape to dwarf his figures. This is rubble too, the wake not of rioting but of economics and exploitation. The film ends with a collage of faces, a building crescendo of workers’ voices rising in a populist plea.

After the 1970s, Haile’s films would touch on subjects of the African American experience, from the struggle of veterans to the horrors of slavery. But he wasn’t the only filmmaker at UCLA who used collages of faces to speak the feelings of his home community. Back in America, here were the faces of Watt’s a decade after the riots.

The film was Jamaa Fanaka’s Welcome Home Brother Charles. While most of the LA Rebellion’s filmmakers produced a counter aesthetic to the exploitative images of Blaxploitation, Fanaka made liberal use of funk music, violence, crime stories and jive talk. His films have been called Trojan horses, vehicles of subversion in the guise of popular trash cinema. If you believe IMDB, Welcome Home Brother Charles is a film about a black man who uses his enormous penis to murder police officers. It was even renamed and marketed under the much more lurid title, Soul Vengeance. But the film is more concerned with the struggles of recidivism, the challenges facing black men returning to their communities following jail time. Fanaka returned to this subject for the far more accomplished Penitentiary. And here too is another face the likes of which would have been rarely seen in most other Blaxploitation pictures:

The man is a convict. He is involved in a vicious battle with his cell mate. The scene is every bit as intense and violent as the alley fight in They Live, a conflict of skin and fluids. The scene’s desperation moves it past exploitation and into commentary. This is the black body brought to war with itself. Throughout, the film’s characters struggle with the idea of returning to society after years in prison. Fanaka’s depiction of the black experience was deeply considered, which makes his regressive portrayals of women and homosexuals all the more disappointing. His use of sexual interludes in Penitentiary is particularly gratuitous, and his consistent portrayal of women as either prostitutes, deceitful or both can sometimes overshadow his deeper messages.

The LA Rebellion, however, featured numerous female filmmakers. While still a student in 1977, Jacqueline Frazer’s Hidden Memories featured frank depictions of domesticity and abortion. Perhaps more importantly, the film provides a counterbalance to the expressly political work of Haile and Fanaka. This is the normalization of the black experience, African American’s stories told not as they relate to poverty or to race, but as they relate to each other and their own fears and pinings. That same year saw Julie Dash’s Diary of an African Nun, an adaptation of a short story by Alice Walker that confronted race and the roles of women within the Catholic Church.

The creative groundswell of the LA Rebellion lasted through the 1980s. And while looking at its films doesn’t give us a complete alternative to Blaxploitation, it does provide a window into the era’s artistic and political undercurrents. These films were by no means as popular as the more successful Blaxploitation pictures of the time. But their existence serves as counter narrative. They help prove that Blaxploitation was a genre that has since been mistaken for an era.

Many films of the LA Rebellion were never widely released, or have since only become available to a wider viewership thanks to UCLA’s continuing preservation efforts. Killer of Sheep, as iconoclastic as it is, had been unavailable publicly for decades due to music licencing issues. It only earned a DVD release in 2008. It is because of the uncovering of many of these films, and their recent availability through the preservation efforts of UCLA, that we are able to construct a more complex view of black cinema in the 1970s, even more so than contemporary audiences at the time. We are armed in ways unavailable to those who came before us, capable of assessing the 1970’s in a way that allows us to transcend the stigma of Blaxploitation and apply a wider, more far reaching perspective to its films and figures.

Next week: Van Peebles, Parks and the divided self.