In the 1970’s, African American cinema was overwhelmed by the hyper-masculinity of Blaxploitation, and Gordon Parks and Melvin Van Peebles have become synonymous with the genre. Peebles’ Sweet Sweetback’s Badasssss Song was among the first films to tap into the appetite for low-budget, violent manifestations of black rage, while Parks’ Shaft gave the genre its most iconic character and theme song. But looking beyond these men’s most popular films reveals two artists who didn’t begin with Blaxploitation so much as arrive at it. Their earlier work constitutes not just a wide range of aesthetics and storytelling styles, but complex representations of African American life.

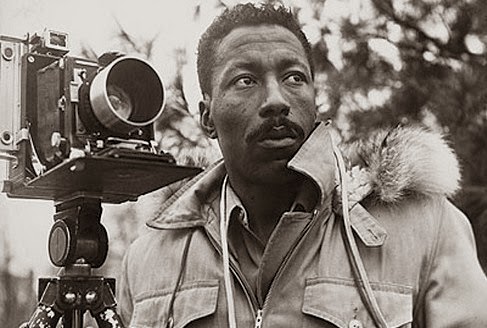

In the late 1960s, Parks was a bestselling author, a composer, a poet, and a staff photographer for LIFE Magazine. It was this eclectic pedigree that led Warner Bros. executive Ken Hyman to approach Parks with an offer to direct an adaptation of his own novel. Van Peebles was an expatriate living in Paris, a director of short films for the Cinematheque Francasaise. He was an author as well, and with a grant from the French Cinema Center, he directed his first feature just a year before Parks. Though separated by an ocean, both films demonstrate the internal divisions of African American identity.

Parks’ The Learning Tree is set in rural Kansas in the 1920s. Its young protagonist, Newt, is characterized by curiosity and naiveté, gazing at moths in microscopes and asking his mother gingerly about heaven. “I’m scared of death,” he says, traumatized after having to fish a man’s corpse out of a lake. Newt is contrasted with Marcus, the son of an alcoholic farmer whose run-ins with the law fuel his intensifying anger. When the two boys are caught stealing apples from a white farmer, Marcus beats the man violently with a whip. Newt defends him, creating the film’s central conflict of liberalism vs. radicalism.

Newt’s idealism leaves him trying to find the good in his white neighbors, while Marcus lashes out with anger and violence. The film’s world is perhaps unrealistically progressive. Many of the white characters possess a forward-thinking attitude towards race, often articulated in didactic speeches which feel more like sermons from the late ’60s than authentic expressions of character. But The Learning Tree is buoyed by the complexity of its characters. Parks never tells us that anger does not exist within their souls, but he contrasts that anger with gentleness and curiosity. Marcus’ incarceration is intercut with Newt’s puppy love courtship. Here are the two roads a young black man can take, Parks tells us, the difference between them sometimes nothing more than the chance influences of one’s upbringing.

Van Peebles’ The Story of a Three-Day Pass is even more explicit in its portrayal of the divided black self. It follows a young American serviceman stationed in France as he goes on furlough. One of the film’s first conversations is between the man, Harry, and his own reflection. He voices his guilt over the fact that the accompanying promotion only came as a reward for his meek attitude, for his status as a “good negro.” He goes to a bar and imagines his spirit leaving his body to approach a girl, self literally separating from self.

Harry is the kind of character who would all but vanish over the coming decade, a young black man whose mannerisms are openly innocent. He and his girlfriend literally skip through town holding hands. But an innocent comment by a well-intentioned singer drives Harry into a rage. “I’m a person,” he screams, an inner violence revealing itself. Here are rancor and innocence within the same man, Parks’ Newt and Marcus fighting for dominance within the same body. “How can anyone think that black is a compliment,” he wonders. And even as love develops between the boy and girl, we feel the pain of that which can never be. The last words of the film are Harry’s admonition to himself in the mirror. “I told you so,” one half says, after the relationship is over. “Fuck you,” he replies, a final condemnation of his own gentleness.

Stylistically, the film is heavily indebted to the French New Wave. Van Peebles uses jump cuts and dissociative editing to reflect his lovers’ youthful energy, while Harry’s long raincoat and dark sunglasses recall Jean Paul Belmondo. Story of a Three-Day Pass was the French selection at the 1967 San Francisco International Film Festival, whose organizers were reportedly shocked to find out that a black man directed it. The film’s success would be enough to land Peebles a three-picture deal with Columbia. But its hard truths about pain and guilt were perhaps too immediate to draw crowds. Instead, Van Peebles next film would express a lurking, existential duplicity in a much different way.

If it’s jarring to watch Godfrey Cambridge in whiteface for the first fifteen minutes of Watermelon Man, consider that before the intervention of Van Peebles, the part had been intended for Walter Matthau. The story of a white man who wakes up one morning as a black man would have involved Matthau spending the entire film in blackface. Instead, Watermelon Man is a strange amalgam of the offensive and the subversive, constantly undercutting any potential satire with sitcom hamminess. The soundtrack punctuates slapstick set pieces with wacky trombones. There are jokes about gospel singing and black-eyed peas. The whole thing plays out like an extended episode of Bewitched, with Estelle Parsons’ hair even recalling Elizabeth Montgomery’s.

Watermelon Man exemplifies how the closest a black director in 1970 could get to critiquing “the man” was through a black man in whiteface, in a script written by a white person. Van Peebles even went so far as to rewrite the ending without permission, replacing the planned “it was all a dream” coda with an ending that finds the main character settling into not just black life, but the beginnings of black radicalism. The final shot, of his face frozen with anger in the middle of a Pan-African self-defense class, reads like a mini preview of the rage that was to come.

Shining through the film’s tonal dissonance is the same struggle for identity. “I’m white,” the black man yells constantly. The film’s smartest moment comes when he searches desperately through the hair and skin care section of a black pharmacy, loading a box full of whiteners and relaxers designed to make black bodies appear more white. After coating his face in one of these creams, he peels off the layers, revealing a face half white and half black. More than just a “man learns lesson through magic” movie, Watermelon Man is Peebles’ struggle to say something meaningful about race relations from within the Hollywood system. He would go on to say that the majority of his energy during the shoot went into fighting the contradictory demands of the studio. Turning his back on his three-picture deal, Van Peebles began moving towards self-financing what would become Sweet Sweetback’s Badasssss Song.

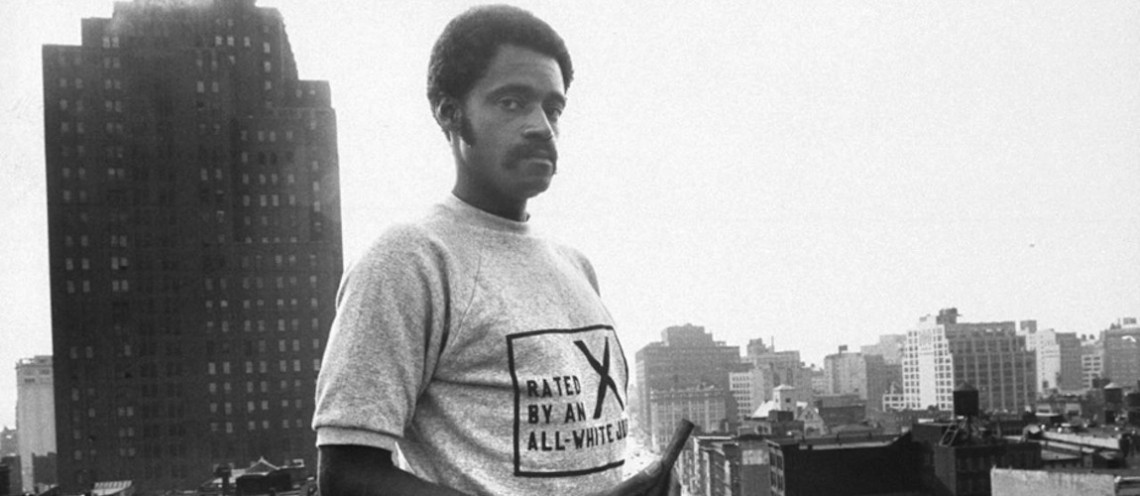

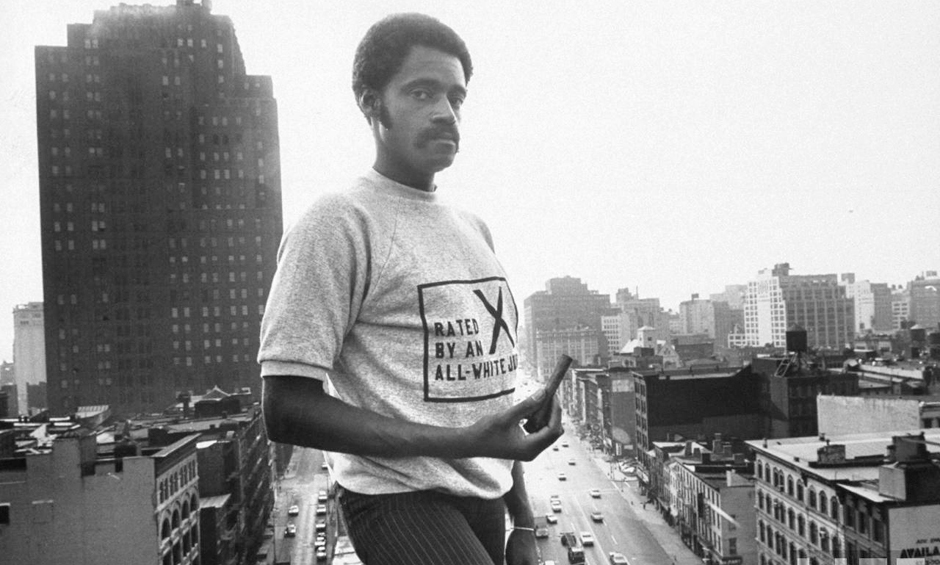

Released in April of 1971, Sweetback announces itself as “a hymn from the mouth of reality,” and gives first billing not to Van Peebles but to “The Black Community.” The film is like the release of Van Peebles’ pent-up id, distorting LA and Southern California into a fever dream of shadows, barren landscapes, and oil derricks. Van Peebles loops sound and lays images over top of each other. He shoots in hallucinatory negative and shoves frames inside frames. Collectively, it’s the visualization of every ounce of frustration that had caused Van Peebles to reject his Hollywood contract. Sweetback’s spree of revenge and subsequent escape is a political statement against institutionalized white corruption and power, one potent enough to overcome even Van Peebles’ surprisingly wooden performance as the nearly silent titular character. Sweetback doesn’t need to speak; he communicates through action.

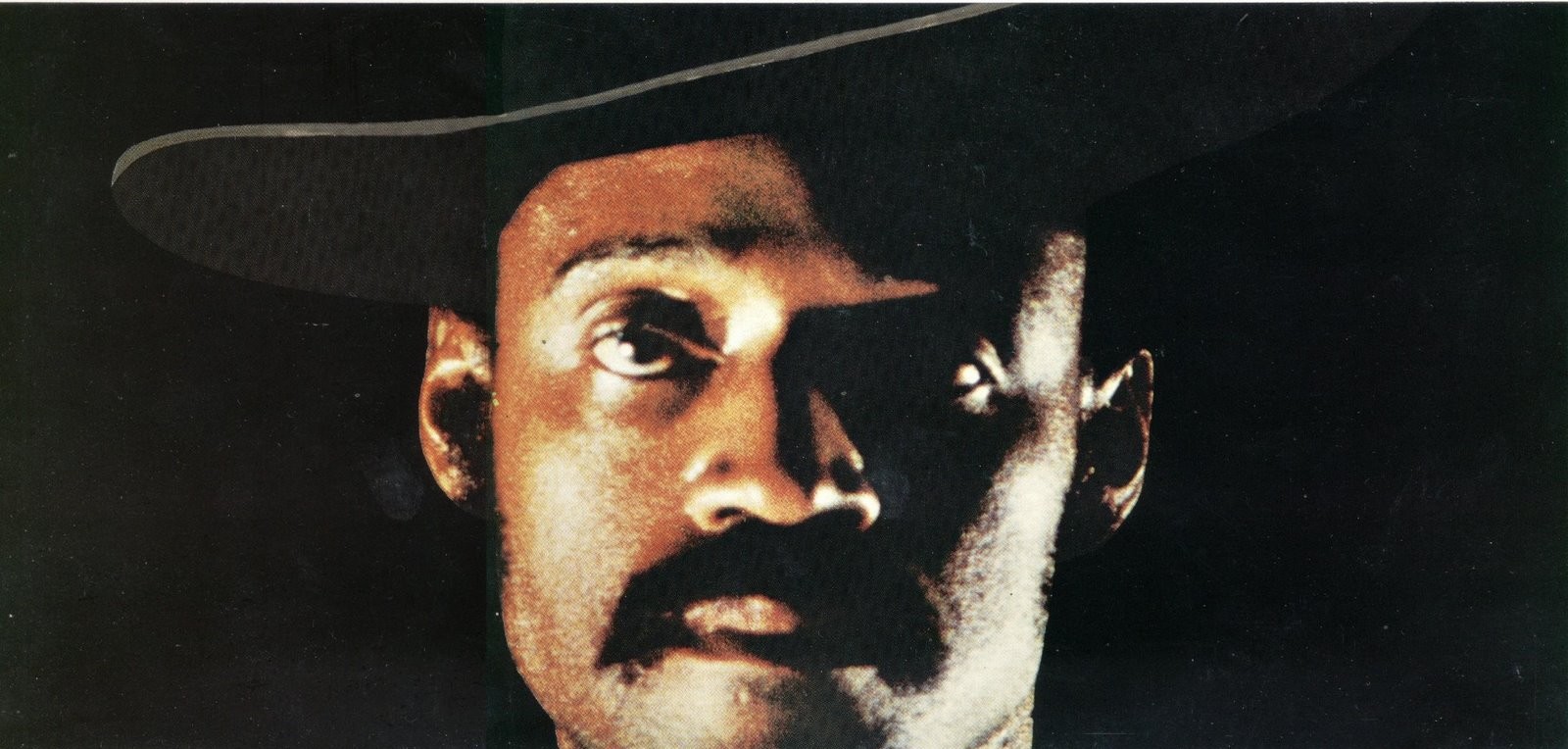

It was this language of action that would be reiterated in July of that same year in Parks’ Shaft. Produced with Hollywood money, Shaft is still almost as bold as Sweetback in its depiction of an unapologetic black man who refuses to take shit from anyone — white, black, or otherwise. Watching these films must have been a cathartic experience for black audiences who had rarely, if ever, seen black man at the center of films, let alone a man so cocksure. Shaft strolls through downtown Manhattan all but daring taxis to hit him, a lack of concern that infuses him with an aura of near-invincibility. He fucks white women, kills cops, and lives on to haunt “the man.”

Looking at Shaft and Sweetback together does more than just tell a story about the growing frustration of black filmmakers or the desire of audiences to see fictionalized manifestations of early ’70s explosive racial politics. The two films illustrate how complex depictions of black identity gave way beneath the allure of unchecked aggression. According to Parks himself, from a conversation with Roger Ebert in 1972, he preferred The Learning Tree to both of his eventual Shaft pictures combined. The same interview marked his vow to pull out of black filmmaking altogether, based on his desire to avoid becoming stigmatized as a black action filmmaker.

Parks, then, instead of the creator of a genre, is better described as a deeply humanist artist whose career was narrowed by the impending expectations of what a black film should look and sound like in the 1970s. At the time, Parks hoped to shoot Peter O’Toole and Vanessa Redgrave in a World War I period piece. The project fell through, leaving Parks to direct The Super Cops, about a pair of kung-fu-chopping white police officers. Van Peebles fought for years to finance more films, but never managed to repeat the financial success of Sweetback, nor the critical success of Three-Day Pass.

Opposition to Blaxploitation within the black community began almost immediately. Following the release of Shaft, it only took Newsweek two months to publish Henry W. McGee’s “Blacks vs Shaft,” voicing the disapproval of figures that ranged from film critics to civil rights activists. “A fairy tale treatment of black life,” Riley called these films. Others went so far as to launch the Coalition Against Blaxploitation, whose duties included a black specific film rating system.

Writing for The Harvard Crimson a year later, McGee would call the current state of black cinema “a cruel hoax played on the black community,” offering only “roles that perpetuate derogatory stereotypes or create counter-productive myths.” McGee quoted COB founder Junius Griffin’s belief that “The transformation from the stereotyped Stepin Fetchit to Super Nigger on the screen is just another form of cultural genocide.” McGee is critical of the entire Shaft series in particular, decrying its lionization of the “self-centered hustler” and its objectification of women. Politically retrograde, exploitative of black actors and audiences, and full of mixed messages about everything from drugs to community organizing, McGee paints a bleak picture of the era’s black cinema.

And McGee can’t really be faulted for his short range assessment. He would have likely been unaware of the work being done by the black film students at UCLA, and it would have been impossible for him to see how the ensuing decade would ultimately play out. He criticizes the cocaine romance of Superfly, directed by Parks’ son Gordon Parks Jr. But he could not have expected that Parks Jr. would go on to direct the gentle romance Aaron Loves Angela, or the genre-bending western Thomasine and Bushrod. Perhaps the weakest element of the staunch anti-Blaxploitation position, however, was its oversimplification of the genre.

There are miles of territory between Sweetback’s legitimate explosion of pent-up rage and the countless films made to capitalize on it afterward, many of them written, directed, and produced by the same kind of white men whom Van Peebles had turned his back on. And there lies much variation among the Blaxploitation films made by African Americans. Comparing the psychedelic anarchy of Sweetback with the reserved cool of Shaft reveals a genre which, at least at its inception, still spoke in a variety of voices, even if they were all violent and misogynistic.

Paragons of macho power fantasy were natural manifestations of systemic disenfranchisement. The machismo personified in the likes of John Shaft and Superfly is an understandable, and in many way reasonable, articulation of the frustrations that had accompanied cinema’s refusal to provide central roles to black characters. Call it the realization of the destroyer Shiva in the absence of Shakti the life bringer, or Yang in the absence of his murdered brother Yin. To western Slavic tribes, it was the lunar darkness of Chernobog without the daylight brought by Belobog. Philip K. Dick described it as the phenomenon of the eternally recurring twin, androgynous beings spinning in opposed directions. In more contemporary terms, it’s that part in Superman III where Superman is split into two versions — one a squirmy, powerless weakling, the other a belligerent, violent sociopath. Without gentleness to offset itself, black cinema traveled further and further into a self-perpetuating rabbit hole that often deserved many of the criticisms placed upon it.

But just as in Superman III, that gentle aspect was still wandering the world. And though Blaxploitation spoke so loud that its echoes still swallow up everything in its path, gentler, less violent films were still being made by and about African Americans. The wide spectrum of black expression was anything but dead in the 1970s.

Next: A Few Words About James Earl Jones