Alex Ross Perry’s fourth film, the paranoid thriller Queen of Earth, marks a departure for the 31-year-old director, though in a sense he has been diverging from both his work and that of his peers from the start of his career. With its ambling photography and rudderless, nearly incomprehensible protagonist, Perry’s 2009 debut Impolex fits nominally within the confines of “mumblecore” to which so many independent filmmakers were reductively lumped at the time. On closer inspection, however, it shares almost nothing in common with its kin: it’s shot not on cheap, easily recorded digital video but Super 16; replaces amateurish improvisation with oblique but clearly written dialogue; and it adds a legitimizing literary filter by (very, very) loosely adapting Thomas Pynchon’s famously dense Gravity’s Rainbow.

The groundwork for Perry’s subsequent three features, each wildly different from Impolex, can nonetheless be traced to the ambitious and perceptive manner in which the filmmaker totally adapts the material in the 2009 film, not simply transposing it for the screen but fitting it into a contemporary milieu. Pynchon’s Slothrop was an oversexed reaction to an undersexed society, so deprived of pornographic release that he got off on the phallic properties of rockets. Perry’s Tyrone S. (Riley O’Bryan) is the inverse, someone so inculcated in a sexualized society that he symbolically totes a dud V2 under his arm that he occasionally buffs to no effect. (Early in the film, Tyrone confesses that his biggest fear is that there are so many rockets now that his own might not stand out from the rest.) Furthermore, the counterculture drugs that hang implicitly over the WWII-set novel have been replaced with a kind of plodding sense of absolute purpose even in the face of senselessness, LSD swapped for Adderall. The potent danger of the novel is replaced by lethargic trips through woods, and the only action to speak of comes from the constant, surreal intrusions of Tyrone’s Stateside girlfriend (Kate Lyn Sheil), whose baiting insults constant verbal warfare.

The latter detail is the aspect of Perry’s filmmaking most commonly shared among all his features. Though the relationship types shift with each film, the notion of conversation as battle remains constant. In The Color Wheel, two siblings (Perry and co-writer Caren Altman) lob vicious barbs laced with casually offensive references to everything from child molestation to the Holocaust in an attempt to tie the petty failings they see in each other to profound horrors. Professional jealousy pervades Listen Up Philip, which pitches the constant jockeying for position between New York’s creatives as so vicious that they could be the gentrified heirs to the brawling immigrant communities of Gangs of New York. The central author (Jason Schwartzman) spars frequently with his aspirant peers, but the true conflict can be found in the toxic, borderline Oedipal relationship between Philip and mentor Ike Zimmerman (Jonathan Pryce), who uses his own rich body of literature as a cudgel to beat his resentful fan with passive-aggressive reminders of superiority. Queen of Earth, meanwhile, turns to the frayed friendship between the haughty Virginia (Katherine Waterston) and the unraveling Catherine (Elisabeth Moss), the former regularly baiting the latter into exploding so she can tease her further for her madness.

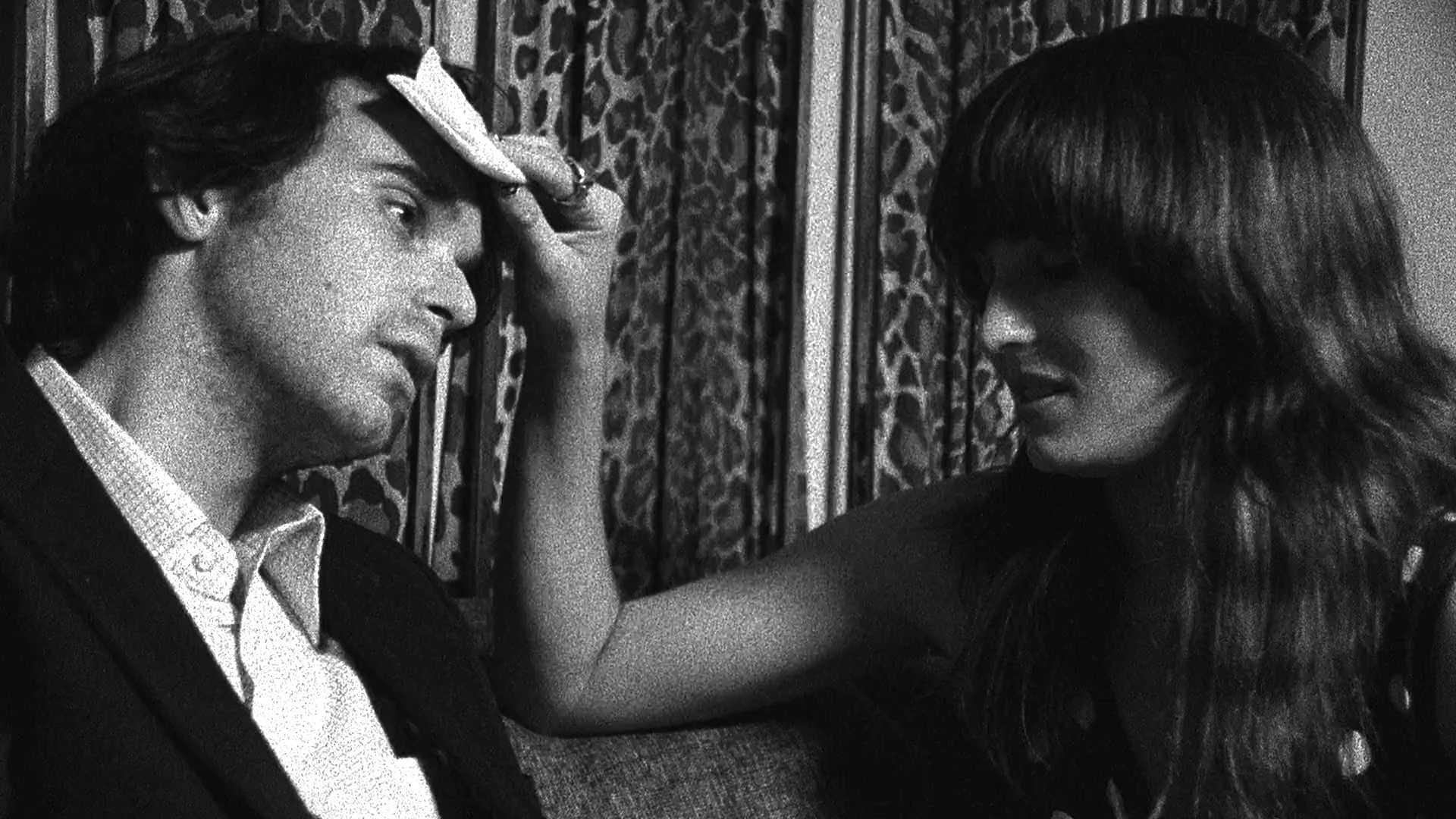

If Perry’s acidic dialogue unites his films, his ever-changing, exploratory aesthetic produces wildly different results with each feature. Impolex offers, as previously mentioned, a riff on mumblecore that replicates the use of close-ups to communicate emotional isolation but also experiments with sun-soaked frames that have the feel of home movies, mixing direct sound and incongruous samples of WWII-era pop music, heavy with vinyl crackle. This half-straightforward, half-parodic rendition of prevailing indie norms was upended for The Color Wheel; cinematographer Sean Price Williams swaps out the sunny but dulled textures of the previous movie in favor of deep focus and a semi-verité quality that once defined cinematic realism but now comes off as a distancing affectation, deepening Perry’s circumnavigation of contemporary style. Shots begin from a distance to emphasize the gulfs of space the protagonists subconsciously place between themselves and the only people they hate more than each other: everyone else. As that antagonism moves from sibling spats to a team effort against former friends and partners, the frame compresses, using zooms, press-ins, and cuts to isolate the leads while bringing them closer together until the taboo-breaking finale suggests that they are the only people left in each other’s lives.

Befitting its literary conceit, Listen Up Philip is altogether more classically composed, with lush, velvety 35mm, vibrant color mixing with handheld camera work to make a film that mimics the combination of sweeping prose and intimate psychology to which its writer characters aspire. This approach pays off most fully in a close-up of Moss’s Ashley right after she dumps Philip for good, the shot lasting long enough that the poor woman’s exhaustion and anger give way to a sense of relief that seems to start off-screen down in her toes and work its way up to her face, which is lit beatifically, like Christ realizing “it is done.” Her close-up is the kind Norma Desmond would demand, one lit by the actor’s own star power. In that moment, the aesthetic leap from previous films signals an equally important step in Perry’s narrative development: here, at last, is someone who opts out of the incessant wars of emotional attrition that motivates the insults that dominate Perry’s films, getting both the last word and peace of mind.

That payoff marks not simply a growth for the director in terms of writing or directing talent but a full evolution, something that can be seen throughout his filmography even when the movies themselves take left turns that thwart linear connections between his work. The most significant aspect of Perry’s increasing confidence as a filmmaker is his deepening facility with actors. Impolex foregrounded halting, clumsy speech that made even the great Kate Lyn Sheil sound as if she learned her lines phonetically, while The Color Wheel effectively steered both Perry’s and Altman’s flat sneers with a script built around their voices. But Listen Up Philip not only lands name actors but gives them all career-highlight performances, whether providing Schwartzman with the most toxically arrogant yet relatable character of his career (no mean feat), or letting Pryce flex his dark comic chops with Ike’s condescension, forever sold with a mocking leer as if to ask Philip “Get it?” after each witty, veiled insult.

Moss steals that film from both actors, but it’s only preamble to the work she gets to do in Perry’s most blatant actor showcase yet. Queen of Earth pushes each of its lead actresses to their most vicious; Waterston reprises the eerily detached teasing that she brought to Inherent Vice, presenting herself as a friendly, relaxed presence even as she lobs mortars at Moss’s Catherine with the uncaring dutifulness of an artillery commander. In this film, as in Paul Thomas Anderson’s, Waterston excels at playing a friend or lover’s worst nightmare, the person who knows every one of their insecurities and feels no inhibition in airing them for humiliating sport. Moss, meanwhile, does not simply emote but traverses each emotion as if it had its own topography, scaling mountains of madness and cascading into depression. The camera regularly segments Catherine in the frame, hiding her face behind her painter’s easel and canvas, let her leaning her head against a pole until it flattens a cheek into two-dimensionality. But it is Moss’s utter lack of self-consciousness—forever trembling, arguing, hunching over with childish giggles, and seizing into frozen horror, among other full body reactions—that truly sells Perry’s throwback thriller.

In some ways, Queen of Earth is a step back for the director, replacing Philip’s readily identifiable millennial climbers with characters informed less by actual social circles (however narrowly drawn) than older movies, namely the apartment films of Roman Polanski. Yet it is often the case that a minor effort from a true talent can be as revealing as a major one. If Perry made the film to test himself, he ends up with his most impressive technical experiment to date, pushing his partnership with Williams to new heights and gradually replacing a film made of subtle quotations and vague approximations with something wholly Perry’s. There are copious visual delights to be had: the fuzzy, fauvist sunsets out on the lake; the use of the open-ceiling home to create multi-planar split-screens out of the same frame; the claustrophobia created by people standing in deep background. It may start as a traditional horror film, but it ends as one oriented around the underlying fear that pervades Perry’s filmography, that of being exposed to the judgment of others without any layers of self-protection. The film also contains what may be the quintessential Perry scene, of the two friends engaged in a lengthy, emotionless, but vaguely remorseful discussion of a shared history as the camera gently drifts between close-ups that completely isolate each character and two-shots that, somehow, seem even lonelier.

—

Original illustration by Krishna Shenoi.