Some actors treat their profession simply like a job. When asked about acting, Spencer Tracy famously offered the following: “Come to work on time, know your lines and don’t bump into the other actors.” But Tracy’s workmanlike approach is certainly not the only one. Other modes of performance—like the famous “method” approach—manifest themselves more internally, demanding actors to reach deep into their inner core. It is this more psychologically draining approach to acting that has led to a kind of subgenre of self-reflexive films about actors in crisis. In such films, acting means pulling oneself inside out psychologically; that is the special appeal of films about actors in crisis, for they display the private delicacy of showing too much, too little and just enough.

One recent entry into this group is Olivier Assayas’s Clouds of Sils Maria, in which Juliette Binoche plays Maria, an aging actress struggling to perform in the same play that helped catapult her to stardom 20 years ago. Now that she is playing the role of middle-aged Helena instead of the younger Sigrid, she is forced to face her own fear of aging. Maria, however, is merely one in a long line of actor-characters in the movies whose onstage personas and offscreen troubles blend and blur. In Marcel Carné’s Children of Paradise (1945), John Cassavetes’s Opening Night (1977) and Richard Benjamin’s My Favorite Year (1982), the actor-characters also find themselves unhinged, dangling on the thin thread where life imitates art and vice versa. As they examine their own artistic limitations, these characters’ turmoil bleeds over the cinematic frames into the audience’s perception, forcing us to look at the constraints of the medium itself.

Actors in the three films see characteristics of their performances echoed in their own troubled lives. In Children of Paradise, Baptiste (Jean-Louise Barrault) is a talented mime who is in love with the much coveted Garance (Arletty) and yet, like the silent clown he portrays on stage, he is unable to declare it publicly. However, typical of the trade he is in, Baptiste is wonderfully expressive in his actions. At one point, despite his slight frame, the mime fights off a crowd of hoodlums to get Garance out of a tavern. Alas, without words, his actions are not enough, as Garance is temporarily wooed away by Frederick (Pierre Brasseur), a Shakespearean actor who is no stranger to sweet-talking. The most heartbreaking scene in the movie is when reality and drama clash onstage. Baptiste’s character, walking comically on a treadmill, contemplates suicide because he can never attain the love of the beautiful statue, ironically played by Garance herself. As he looks offstage with a frustrated expression, the camera cuts from a close-up of his face to a point-of-view shot of backstage as he sees Garance and Frederick embracing. The scene then cuts to a close-up of Baptiste’s face again, now pained with melancholy. Both Baptiste and the character he plays onstage have become united in the same emotion: the loss of hope for a requited love.

Gena Rowlands’s and Peter O’Toole’s actor-characters in Opening Night and My Favorite Year, respectively, face the same crisis. Myrtle in Opening Night is a stage actress who has to perform the role of an aging woman longing to find love again. Haunted by a young girl who dies while trying to see her after a performance, Myrtle reflects upon her metaphorical and literal loss of youth and wonders whether she could portray old age when she does not even understand what it means to be young. Meanwhile, O’Toole’s alcoholic movie star Alan Swann is another character who witnesses his own personal demons crossing into his professional life. Throughout the course of the film, Alan, the once famous swashbuckler star, struggles to sober up for a live-television performance where he portrays a parodic version of his iconic valiant persona. Even though Alan Swann is modeled after Errol Flynn, the character reflects O’Toole’s own alcoholic problems (he had to cut off half his stomach due to alcohol abuse shortly before starring in the film). If Baptiste in Children of Paradise is so good of an actor that he is unable to separate his stage role from his offstage identity, Myrtle’s and Swann’s egos and personal problems overwhelm their acting ability.

As real life and make believe collapse onto each other, the actor-characters reach dead ends where they have no other option but to look honestly at themselves, as professionals as well as individuals. Even though all three films deal with markedly different forms of acting, they all prominently feature, naturally, a mirror motif. To perform is to be looked at, whether by the audience or by the camera, and thus, these characters scrutinize themselves, sometimes to the point of obsessiveness before they can be exposed to others. In Children of Paradise, after seeing other men going to Garance’s dressing room—a scene that plays like an audition for the role of her lover—Baptiste gets frustrated and declares that he hates himself. Pointing to his own image in the mirror, he draws a big X on his head and screams for his own death. Baptiste might be the big star on the stage, but he has failed at his biggest audition in real life: winning Garance’s heart.

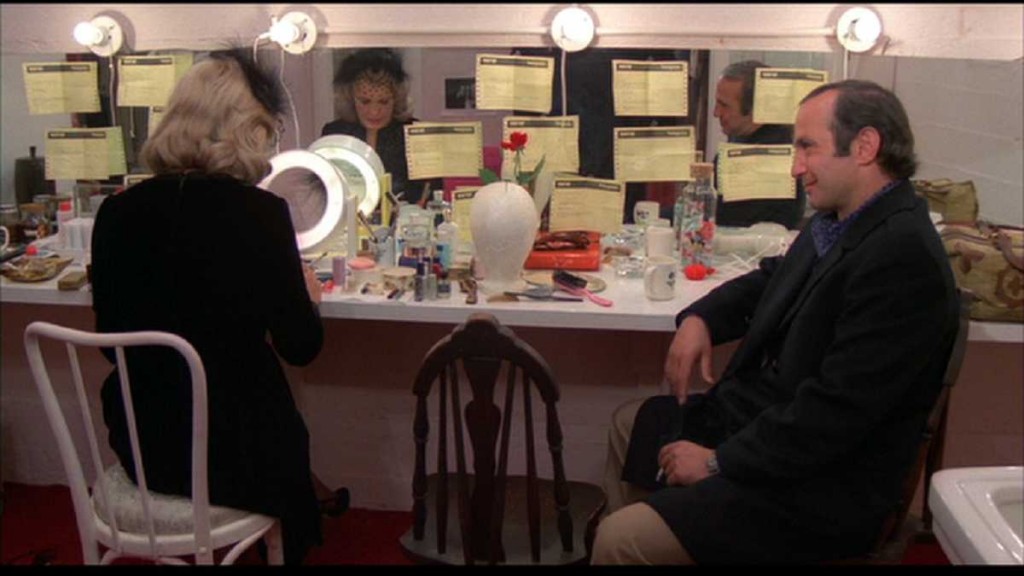

Similarly, in Opening Night, Myrtle also sits in front of a mirror to prepare for her performance. Her reflection is obscured as the mirror is covered with numerous yellow pages of the script—a beautifully expressive image that offers a constant reminder that onstage, only the character she plays matters. And yet, the producer keeps telling her that she is not funny anymore, prompting the actress to look at her own personal changes in relation to her middle-aged character. Each time the film returns to large mirror, the camera inches closer to Myrtle’s reflection until we no longer see those script pages. Myrtle’s own inner life has taken over the stage. Now the play is not just a literary device but an existential battlefield where the actress battles her own mortal fear.

Instead of looking at a mirror, Alan Swann in My Favorite Year looks at movie clips of his earlier performances, fighting off the bad guys in cheesy swashbuckler montages. The result is even more existentially terrifying: Swann recognizes himself in the footage, but he also realizes that those images are an idealized version of himself. “I’ll try to get it right on the first take,” says Alan optimistically near the end of the film, only to be informed that with live TV, he only has one take to get right. For the first time, Alan Swann looks at himself from the film crew’s point-of-view. When movie magic disappears—when he no longer has the luxury of multiple takes—could he still call himself an actor? The moment Alan Swann’s illusion of his own acting ability is shattered, he suffers a full-blown anxiety attack, running around and screaming, “I’m not an actor, I’m a movie star!”

As the fear of being unable to act, or of acting too convincingly, is put on display, the three films inspire a sense of reflexivity. At one point in Opening Night, Myrtle contemplates, “If I can reach a woman sitting in the audience who thinks that nobody understands anything and my character goes through everything that she’s going through, I feel like I’ve done a good job.” Because Opening Night, being a film, lacks that immediate response present in live theater, John Cassavetes conceives of dreamy, surrealistic sequences that ease in and out of Myrtle’s consciousness—a feat of psychological penetration that would not be as effective onstage. Thus, the film proposes a balance between theater and cinema. On the one hand, the camera moves freely, even manically at times, as the actors improvise on stage. However, once the inner life of these characters is displayed, the camera no longer stays at a respectable distance, instead inching uncomfortably close to their faces, spreading their often anguished expressions all over the screen. Film’s unique power is to reach into the utmost depth of human emotions, and Opening Night showcases just that, ironically through an actress who temporarily cannot act.

The most emotionally affecting moment of reflexivity in the three films is in My Favorite Year when Ben (Mark Linn-Baker), the TV station’s freshman writer and temporary babysitter for Alan Swann, says to his disheveled movie idol, “Why does it matter that it’s an illusion? It works.” Finding temporary inspiration in this, Swann rises to the occasion, punching a few bad guys at the end, both as himself and in character on live TV. The moment in which Swann waves to the audience and, by extension, at us in the movie-watching audience is incredibly moving in its implication that, for Swann, image and reality have aligned at last.

In looking at these films about acting, the question remains whether the ultimate goal of performing is the ability to comfortably strut through the crossroads of fiction and reality, without one’s own personal crisis bleeding into his/her performances. Children of Paradise, Opening Night and My Favorite Year don’t propose answers; instead, they offer a sense of ambiguity, a quality that is deeply central to the nature of acting itself as well as instrumental in making cinematic examinations of performance so endlessly fascinating to watch.

2 thoughts on “Acting Out: On the Reflexivity of Actors in Crisis”

Pingback: Page 2: Star Wars, Mad Max, Fight Club, Firefly, Twilight Zone, Fast & Furious, Labyrinth, William H. Macy, Scott Pilgrim | 8a8

Pingback: Page 2: Star Wars, Mad Max, Fight Club, Firefly, Twilight Zone, Fast & Furious, Labyrinth, William H. Macy, Scott Pilgrim - OddPad.com