Alissa Wilkinson has written about pop culture, politics, and religion all over the Internet. She is chief film critic at Christianity Today and assistant professor of English and humanities at The King’s College in New York City. Based in Brooklyn, her work has also appeared in The Atlantic, Paste, Relief, Books & Culture, Marginalia Review, and Criticwire. Tim Grierson is a film and music critic whose writing has appeared in Screen International, Rolling Stone, Paste, Playboy, The Dissolve, Popular Mechanics, and Deadspin. He is the author of five books, including Public Enemy: Inside the Terrordome, a biography and critical reassessment of the seminal hip-hop band. A contributing editor at Backstage, Tim currently serves as vice president of the Los Angeles Film Critics Association. Follow him on Twitter.

Part One

The Deadpan and the Dread

Tim,

Would it be fair to call Don Hertzfeldt one of our best humanist filmmakers?

I mean that in the old sense, where humanism is about the value of the individual, but also how they fit into a society. I also mean it in the sense where people are expected to think for themselves, but where there’s still something more to humans than brains.

I guess that’s kind of a boring, academic way to look at someone who is also about as darkly humorous a filmmaker as I can imagine, not to mention imaginative beyond my comprehension. (“My spoon is too big” has been a punch line in our home for almost a decade.) Watching World of Tomorrow, though, I was struck by how much of what’s in the film is about all the things besides brains—but including them—that seem to make us people.

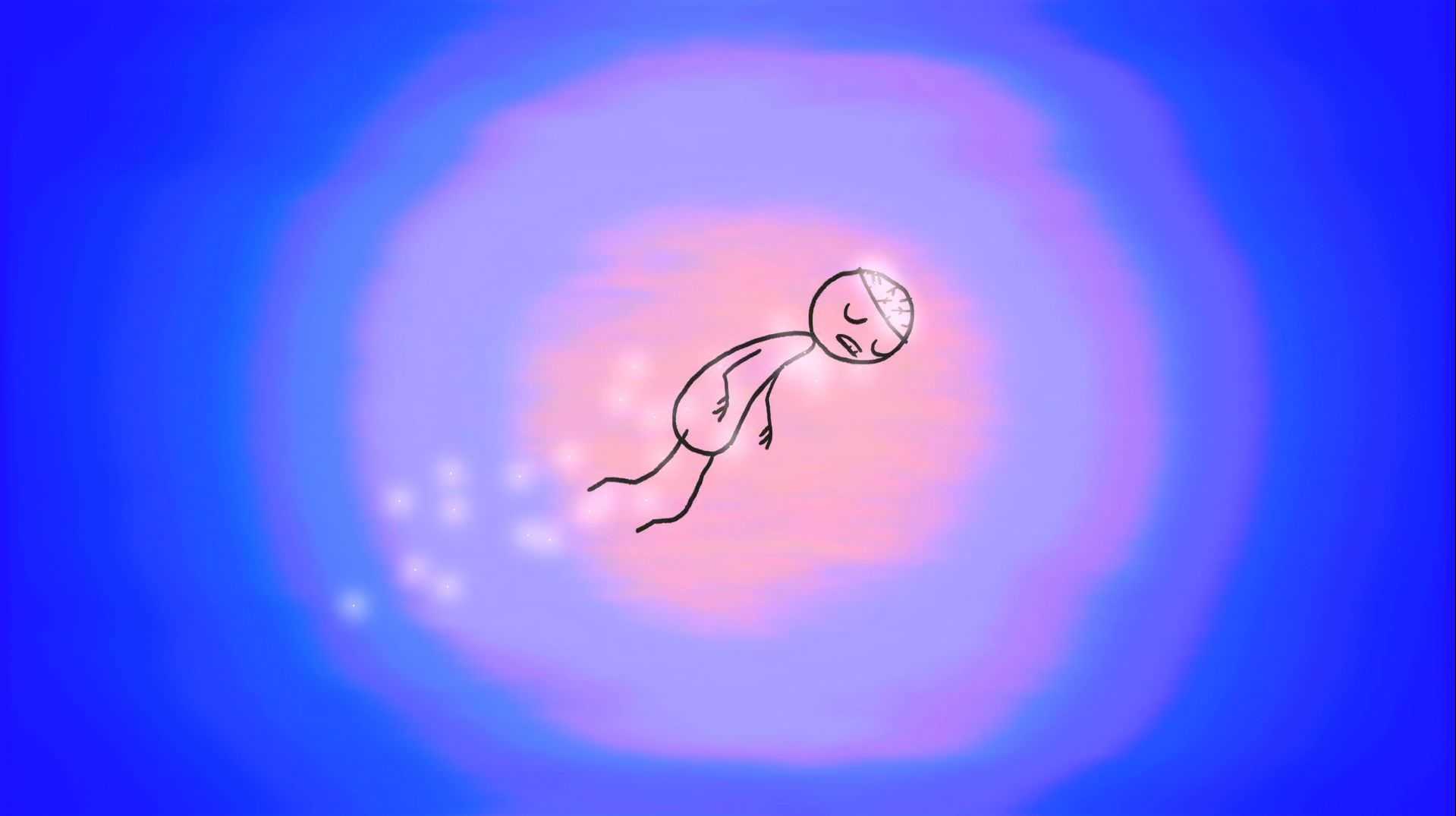

After I saw it—twice—I went back and watched his 2006 film Everything Will Be OK, and confirmed it’s about the same thing as World of Tomorrow. The latter argues, through all the Emilys and Davids and consciousness-encompassing cubes, that when we reduce our humanity to just our minds, we lose something important about being human. On the other side of the coin, Everything Will Be OK suggests that our bodies can fail and mess with our brains. Brains, thoughts, memories: they can get weird and corrupted, because there is more to us than them. We have bodies and emotions and histories. Right?

All that seems pretty cool in an expressionist animator, whose job is to deliver the rational and non-rational, all at once. He’s giving us some thoughts and some feelings, and the latter is less rational than the former. (The older Emily of World of Tomorrow falls in love with a rock, and doesn’t know why, and needs a memory to get through the harrowing days ahead, and also doesn’t know why.) Hertzfeldt’s characters’ line delivery is always pretty deadpan, which is why “My spoon is too big” is so funny. But watching both films, I was unsettled by how well they evoked both the deadpan and the deeply psychic dread of death—of being erased.

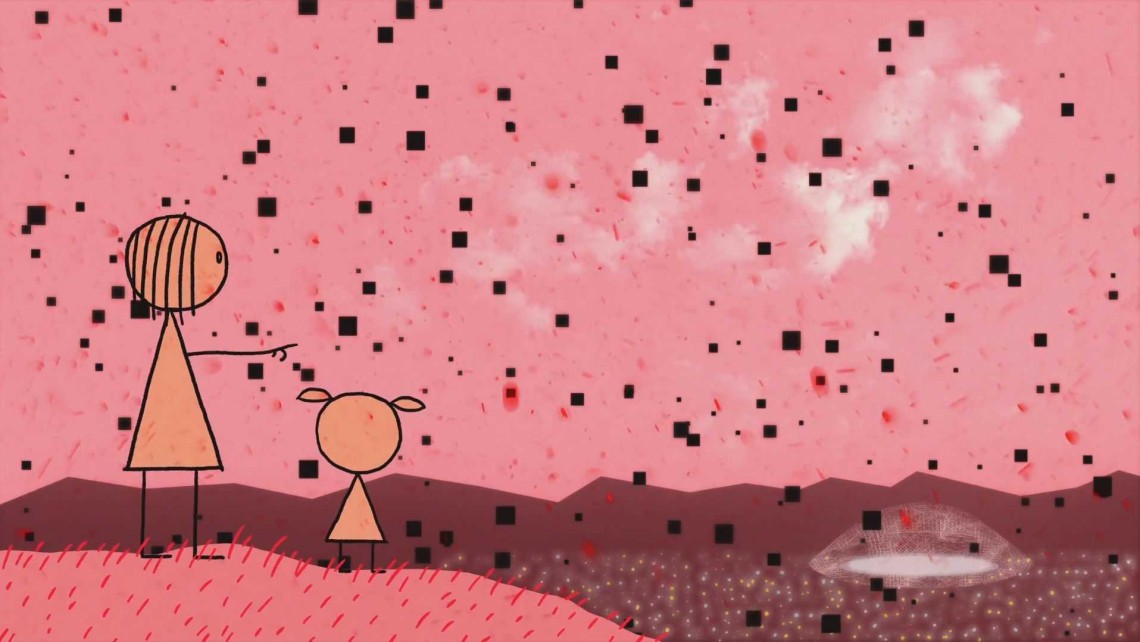

And it doesn’t just do that through the words, though Emily’s line to Emily Prime about why the present must be cherished—“now is the envy of all the dead”—is at least as great a line as anything Nietzsche or Kierkegaard ever wrote. (“Okay,” Emily Prime replies.) Look at those images! The “outernet”—the dread of being lost in space, which is very, very close to a series of nightmares I’ve had since I was a kid. The blinking out of consciousness. Even the very act of animating, which is externalizing the way a brain sees the world, like that gag in 30 Rock where Kenneth sees everyone as puppets. Only connect? Connect how? Hertzfeldt’s doing his hand-drawn best, and it’s great.

Plus Emily Prime (besides being damn cute) is clearly voiced by a real kindergartner who doesn’t really have any idea what lines are, and if there’s something more human than that, I don’t know what it is.

– Alissa

Part Two

The Anxiety of Modern Life

Alissa,

One of the many things I love about Don Hertzfeldt’s work is that, as short as his films are, they’re never about just one thing—and they leave the door open to multiple interpretations. Your reading of him as a humanist filmmaker is absolutely right—and, yet, I’d never thought about it quite that way (and I’ve thought a lot about this guy in the last few years).

Walking into World of Tomorrow, I was sure he couldn’t possibly top It’s Such a Beautiful Day (2012), his hour-long feature that brought together his previous shorts, including Everything Will Be OK and I Am So Proud of You, for a look at the unhappy, mundane life of a guy named Bill. In the years since seeing Beautiful Day, I’ve had a hard time articulating exactly what that movie did to me, how it managed to express all the terror and wonder of modern life with such humor, sadness, and pain—and to do it with an offhand effortlessness that made its profundity seem like a happy accident. But while watching World of Tomorrow, his ineffable greatness came rushing back to me: “Oh right, this is how he does it.” Which doesn’t mean I’m any closer to articulating Hertzfeldt’s strategy—just that I’m grateful he’s continued to fine-tune and perfect it.

From Hertzfeldt’s earliest shorts, he’s been able to latch onto the inherent tension and giddiness that comes from drawing. Deceptively crude, works like Lily and Jim (about a blind date gone bad), Billy’s Balloon (which could almost be retitled Rise of the Planet of the Killer Balloons), and the Oscar-nominated Rejected (in which Hertzfeldt presents his fictional rejected commercial animation ideas) have a naiveté in their illustrations and storytelling that suggests amateurism. But like Andy Kaufman with his goofy voices and guileless playacting, Hertzfeldt uses the pretense of amateurism to get at something primal, joyful, and also deeply strange about everyday life. By stripping away the artifice of sophistication, he says something purer, truer.

Despite its artistry, animation remains, in the eyes of the culture at large, mostly viewed as something meant for children. Hertzfeldt’s films provoke deep thinking—and, as you pointed out, comparisons to Nietzsche or Kierkegaard—but he also taps into the innocence with which we embrace an animated film. Consequently, he gets to have it both ways. I can’t think of any contemporary filmmaker who asks such bleak questions about consumerism, death, God and loneliness with such casual grace. (Just look at the beginning of It’s Such a Beautiful Day, when Bill’s brief chance encounter with an old acquaintance on the street comes to represent all the awkward little social interactions that make up the majority of our lives.) At their core, Hertzfeldt’s shorts are funny-looking cartoons. But their faux-simplicity also makes us anxious—his cartoon universe is one that won’t sit still, won’t behave like a proper, polite, benign animated movie should. We sense the anxiety of modern life intruding in every wiggly line and every flat expression on his characters’ faces.

Which isn’t to say World of Tomorrow, like his earlier films, can’t be oddly adorable at the same time. As you mentioned, Alissa, World of Tomorrow gets a lot of mileage out of Emily Prime’s babyish non-sequiturs, her undeveloped intellect a perfect stand-in for our collective incomprehension in the face of the frightening, unknowable mysteries of existence. Hertzfeldt cast his four-year-old niece Winona to voice Emily Prime, which lends this exceptionally dark, melancholy short familial warmth. “Amateurish” in the same way that the look of World of Tomorrow is, Winona’s performance is all unfiltered innocence, which is both lovely and fragile.

That combo has been part of Hertzfeldt’s work from the start. World of Tomorrow is the filmmaker’s first excursion into digital animation, but he utilizes the tools to suggest the same just-fucking-around primitivism that was the hallmark of his earlier shorts. In his hands, the technology enhances the humanity and sharpens his story’s emotional thrust, rather than becoming a crutch or hindrance.

Part of me wants to revisit World of Tomorrow and It’s Such a Beautiful Day so I can try to unravel the nuanced mixture of emotions they stir in me. The other part of me wants to let that mystery stay unresolved. All I know is his movies express beauty and sadness in such bite-sized portions that they feel far more expansive and epic than their short running times suggest. I can’t explain his artistic secret any better than reporting what I feel after seeing one of his shorts: “My god, that wrecked me. I want to see it again right now.”

-Tim

Part Three

To Look The World Back to Grace

Tim,

I love when you say that “Hertzfeldt uses the pretense of amateurism to get at something primal, joyful, and also deeply strange about everyday life.” Then you noted how this helps us to approach the profound, weighty ideas in his work with “the innocence with which we embrace an animated film.” He turns all of us—even those of us who watch movies and write about them for money—into children, amateurs, for a little bit.

It reminded me of something that one of my favorite writers, Robert Farrar Capon, says in a book about food. He’s writing on how much we forget to notice the world as we run around experiencing it. “That, then, is the role of the amateur,” he writes. “To look the world back to grace.”

But Hertzfeldt himself, as you say, is obviously no amateur. That makes me admire the risks he takes all the more, because he doesn’t stop at coaxing us into letting down our guards. As you note, he then turns around and messes with the world he’s made, wrecking us in the process.

It strikes me that some of this visceral unease is the same kind that belongs to some horror films, the sort where you find yourself staring at the beautiful image on the screen for a while, trying to figure out what you’re looking at, until you recoil in horror—and then the camera cuts away. (I’m thinking here right now of The Witch, which played at Sundance this year, or certain episodes of NBC’s Hannibal.) These are much scarier to me than any out-and-out slasher flick, because they lull you into a sense of aesthetic wonder right before jabbing the knife between your ribs. Fright and beauty, the sublime and the grotesque, being juxtaposed against one another in order to unsettle us and make us look again at the world.

That same knife twists, I think, when we’re watching a cartoon with funny-looking characters that asks big questions, as you say, about “consumerism, death, God, and loneliness with such casual grace.” It’s uncanny. It wrecks us, because it blurs borders between the banal and the extraordinary: line drawings, sometimes absurd ones, with the edges showing, that also act as windows into our own fears, feelings, and lives.

It made me so happy when I realized Emily Prime was Winona, a child, and that her babbling was bouncing off Julia Potts’s nearly-robotic upper-crusty, progressively more devastating narration. It’s a perfect microcosm of life, this stiff upper lip and resolve to stare into the abyss, on one hand, and a tuneful giggling on the other about what a beautiful day it is.

I like to think that the gracefulness with which Hertzfeldt pulls off the big task of exploring existence gets echoed in us, the audience. Because it’s one thing to write a ponderous tome or make a didactic movie about How Life Is Meaningless But We’ll Just Soldier On. It’s another one to make a simple, short film of mostly line drawings that retains mystery and yet gives us some reason to believe we’re not alone in our loneliness.

-Alissa

Part Four

A Hell of A Good Universe Next Door

Alissa,

I completely agree with your assessment of the uncanny in Hertzfeldt’s work: Only 38, he seems to have absorbed all the Big Questions of life and, rather than letting them turn him cynical or morose, has translated their immensity into engaging, often impish stories that are just skewed enough that it’s like we’re seeing the everyday through fresh eyes.

As much as I enjoy albums and full-length films, there is something about a great song or short film (or short story) that can’t be duplicated in any other medium. Albums and films (and novels) have a familiar trajectory—a culturally agreed-upon narrative arc, if you will—that invisibly dictates their shape, creating an inevitable predictability. But a short isn’t beholden to such rules—which must be liberating for the artist, and is also exciting as a viewer.

The best shorts, especially in animation, can tell as small or big a story as they want, and a condensed narrative can focus in on something so seemingly insignificant that it feels enormous, readjusting our perceptions in a way a traditional narrative might not. (For instance, Hertzfeldt’s 13-minute Lily and Jim focuses on a blind date, but it delicately opens up to encompass lots of other issues: how we both crave connection and fear intimacy; how our inability to perceive a situation correctly ends up warping our judgment, as well as our beliefs about ourselves and others.) Whenever I hear an excellent song or see a fantastic short film, I get the sensation that the piece of work has stripped away everything around it, creating its own reality in which the totality of existence can only be fully understood by what I’ve just experienced. The immediate, fleeting rush of a short (or a song) requires our total concentration, and when it’s over it stays with us, like a new truth we’ll carry around with us forever.

Hertzfeldt’s films do this to me repeatedly. And like you suggested, he makes weightier, two-hour-plus dramas—the kind you see during Hollywood’s award season—seem lumbering by comparison. As complex as its futuristic scenario is, World of Tomorrow exudes a feeling of effortlessness, which gives Hertzfeldt’s observations about identity and loneliness a breezy naturalism. We aren’t overwhelmed by the filmmaker’s intellect or sophistication—we just nod along and go, “Yeah, that’s right. This is what living feels like.” Because of their brevity, great short films and songs are little pearls of wisdom, fortune cookies with actual insights tucked inside. In Hertzfeldt’s slivers of narrative, he cuts to the heart of what we’re all carrying around. It’s as if he’s striking chords within us we didn’t know were there.

Critics often compare his work to 2001: A Space Odyssey, mostly because, like Kubrick’s film, Hertzfeldt grapples with heavy themes on an epic, cosmic level. It’s Such a Beautiful Day and World of Tomorrow, as with 2001 before them, are both awed and terrified by the mysteries of existence. (Hertzfeldt’s films are funnier and sweeter, though.) But for me, who considers 2001 the greatest movie ever made, these works are also connected by their bemused, cockeyed wonderment about the questions they’re asking. To invoke your wonderful phrase, Alissa, Kubrick and Hertzfeldt are both making movies about How Life Is Meaningless But We’ll Just Soldier On. But they find human beings too endearingly unreliable and confusing to leave it at that. There’s a sense of boundless possibility in 2001, just as there is in It’s Such a Beautiful Day and World of Tomorrow. By envisioning melancholy futures and anxious presents, Hertzfeldt asks us to dream as big as he does, to transcend the world around us.

I suspect Hertzfeldt knows that our mundane lives are all we have. But he defiantly aligns himself with Emily Prime, staring wide-eyed into the unknown. Inspired by the implications of 2001, Roger Ebert ended his original review by quoting a line from an E. E. Cummings poem: “listen — there’s a hell of a good universe next door; let’s go.” Hertzfeldt wants us to go, too. His movies are the doorway there.

-Tim

One thought on “Don Hertzfeldt: Beauty and Sadness in Bite-Sized Portions”

Pingback: Writing a Critical Review | The Narrative Breakdown