Dirk Bogarde debuted on the London stage at the age of 18 and first appeared on the screen 8 years later in 1947. His first of five BAFTA nominations came in 1961, and his first of two BAFTA wins followed two years after that. A widely lauded career ensued until 1978, when he entered semi-retirement from feature filmmaking, thereafter appearing in two television movies, one TV episode, and one last theatrical release in 1990.

Since early in his film career, Bogarde frequently challenged audiences’ tolerance for those on the margins of society (his star-making turn in The Blue Lamp [1950] has him killing a police constable and still remaining attractive). No matter their flaws, Bogarde’s dashing good looks and brooding sensuality often evoked spectator empathy for even the most unlikely of characters. At the same time, he could equally embody more traditionally heroic individuals: It was his portrayals of war heroes, doctors, and the like that shot him to stardom. After his departure from the Rank Organization in the early 1960s, however, Bogarde acted in a string of films that defied the sexuality of his screen persona up to that point; Victim (1961), the film that garnered him that first BAFTA nomination, features him playing a closeted homosexual during a time when even the term “homosexual” was taboo on screen.

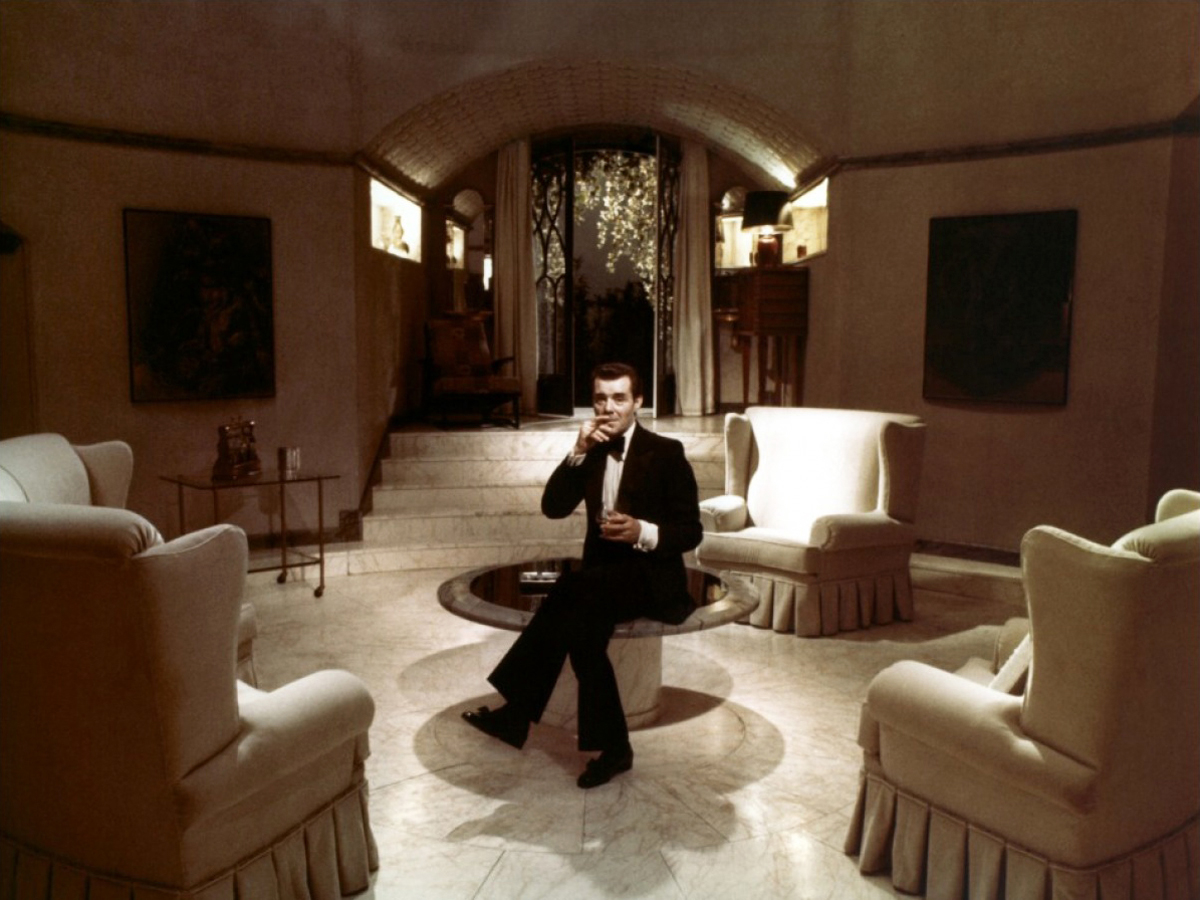

But it is his run of performances from The Damned (1969) to Despair (1978) that stands as Bogarde’s most fascinating period. In five films in particular—The Damned, Death in Venice (1971), The Night Porter (1974), Providence (1977), and Despair—Bogarde dramatically extended his broad talents and topical daring, working with major international directors in a wide variety of contexts, from burgeoning fascism to the depiction of a wrenching psychological breakdown. One theme connects these performances, though: All of his characters suffer under the pressures of a relationship they cannot have, a relationship they do not want, or one they recoil from yet need too much to cease.

Though Bogarde’s Friedrich Bruckmann is one of several figures at play in Luchino Visconti’s The Damned, this rising young mogul-in-the-making is the one for whom romantic relationships take on wide-ranging relevance. Hoping to marry into the reputable von Essenbeck family, lords of an industrialist empire, Friedrich does genuinely care for Baroness Sophie (Ingrid Thulin), but the ambitious gentleman is also fully aware that she is also his ticket to power. His present status may be a result of his own earnest determination, but there is no denying the influence of familial expectations and perceptions.

For her part, Sophie also grows increasingly conniving, actively and vigorously prodding Friedrich along. She too has much to gain, becoming as equally ruthless as her brutal husband, who fully or collaboratively disposes of two family members in order to attain his position. With their cooperative conspiracy, Friedrich and Sophie form a closer bond than the other Bogarde couples in these films. This is a mutually advantageous match, where Friedrich gains from the romantic situation for the progression of his own work and Sophie correspondingly hitches to his ambitions to secure her own livelihood. Though Friedrich painfully admits he “accepted a ruthless logic” in his quest, his pitiless business acumen and maliciousness are genuine. And once his desired rank is attained, he takes to his authoritative role well, barking orders in a zealous manner that clearly excites and pleases Sophie.

Ultimately—in a situation that would be echoed years later in The Night Porter—Friedrich and Sophie are hunted and threatened. Together they remain naively resilient and find some resolution in an insecure moral compromise, one that leads to a most dispiriting wedding ceremony and their subsequent joint suicide. Depressing though it may be, this is one of few instances in these five films of a mutual action between two partners, even if it is one forced upon them.

While none of Bogarde’s relationships in these features are necessarily happy, only in Death in Venice, again directed by Visconti (and adapted from Thomas Mann’s novella of the same name), is there a completely unrequited love. Here, Bogarde is composer Gustav von Aschenbach, traveling to Venice to recuperate from a recent illness. Gustav is withdrawn and meek, and does not exude the confidence of these other Bogarde characters, though he does similarly long for a controlled stability. As he browses a crowd of vacationers, a young boy with golden locks of hair catches his eye. There is an instant infatuation. The boy, Tadzio (Björn Andrésen), begins to exit the room, stops, stares back, and moves on—an acknowledgement of Gustav’s shine, or the first of several teasing provocations? Haunted by his recurring presence, the ensuing frequency of recurring encounters and shared glances imply a purposeful, though perhaps subconscious, stalking. Silently observing—or more precisely, leering—he is forced by decorum and decency to remain inactive.

The unspoken repression leads to feelings of envy when Tadzio frolics with friends. Is Gustav’s fixation based on the boy’s youthfulness, his vitality compared to Gustav’s sickliness, or is it a more carnal physical attraction? Tadzio seems aware of the temptation either way, even seeming to tease Gustav, appearing to strike a pose in some cases. Yet this may be conjecture, with the possibility that these alluring moments are merely in the musician’s tortured mind. Visconti’s use of intense close-ups and slow zooms intensify and isolate the corresponding looks, suggesting an eye-line match that may appear more significant than it is. When Gustav at one point stops face to face with Tadzio, a subtle smile from the boy resonates with an innocence charged with potent titillation. On the heels of this encounter, and after a happy accident brings Gustav back to the hotel, the previously listless composer develops a renewed vigor, the first instance in the film where his joy and satisfaction is evident. He watches Tadzio with a temperate perception, pleased with his childlike antics, presuming a bond that, in all likelihood, is purely a one-sided affair.

In a final valiant attempt to make an impression, Gustav alters his appearance with makeup and hair dye, to no avail. Before he succumbs to his physical and emotional frailty, he sees Tadzio and another boy fight. Gustav, wrenching in pain, expresses protective support and adoring wonderment. Then, with a final glimpse at Tadzio alone, he reaches out and expires.

The connection between Gustav and Tadzio is not the only relationship (such as it is) depicted in Death in Venice. In flashbacks, we see Gustav’s wife as well as a former male acquaintance. The men muse about life, art, and beauty, with no physical engagement, while with his wife and their small daughter, there is a warm affection, a pleasantness at odds with his current coolness. This, it would seem, was the last vestige of a “normal” healthy relationship for the now departed musician.

On the flip-side of a “normal” romance, Liliana Cavani’s The Night Porter, set in 1957 Vienna, features likely the most unconventional affair of these films. Bogarde plays Max, a former Nazi, and Charlotte Rampling is Lucia, a one-time concentration camp occupant who, even after torture and degradation, forms a disturbing relationship with her captor. A chance reunion leaves them both reeling. Their exchange of glances upon first shocking recognition—shot in close-ups of staggering realization—spurs on flashbacks of their initial acquaintance. Max and Lucia recall the cruelty, but to what degree positively or negatively becomes temporarily unclear. In any case, they enter a state of flustered anxiety as it becomes a painfully awkward and naturally complex acquaintance. But when she seeks him out, it is equally apparent that curious feelings remain.

When they eventually meet face to face alone, the greeting is fraught with anger and a succeeding physical assault, a struggle that only rekindles their prior rapport. Before long, they are smiling and kissing on the floor. He pleads with her to tell him what to do, suggesting a past and present need for dependency as well as an ironic twist on the master/servant relationship they had as Nazi/captive. Once reunited, there is evident compassion and a love of sorts, albeit an unsteady one where the violence and humiliation of the past still lingers somewhat.

A degree of trepidation follows, with both hesitant to reenter what is a confusing, tenuous bond. Sequences of silence are infused with tension and an aggressive sexuality. He frequently says he loves her, though she never reciprocates the phrase. There remains a lingering hint of something inhibited, an undercurrent of a sadomasochistic combination of deviant sex and violence. When there is consummation, there is scarcely a difference. Max contends he and Lucia have not a romantic story, but a Biblical one, a proposition that recalls an erotically charged night of debauchery where he bestows upon Lucia the head of a prisoner who had hassled her (she just asked that he be transferred). By this point in their wartime past, a troubling tenderness has emerged, and though she is initially, understandably, reticent, having been subject to his abhorrent actions, she nevertheless responds to such perversely sensual acts as when he provocatively forces his fingers into her mouth.

In the present day, Max’s refrain of “No one must touch her” insinuates a possessiveness born from a bizarrely paternal affiliation; “She was my little girl,” he states, and in the past he had dressed her as such. But though he had authority back then, things have now changed. Under investigation for his Nazi membership, witnesses to his previous life are sought. There is thus a resounding reliance on the maintenance of his reunion with Lucia. He tells investigators to leave her in peace, but that is for his own benefit as well as what is a perhaps genuine concern for her life. When Max locks the two of them away, Lucia defends his actions and denies cooperation, endorsing the restrictions. As eccentric as it may be, this a robust devotion, and it becomes a strangely romantic end to strangely romantic union.

The meandering plot of Alain Resnais’ Providence, coupled with the film’s reliability being dependent upon the hazy, potentially deceitful recollections or imaginings of a dying man, make the relationship at the center of this 1977 feature a complicated one indeed. As played by Bogarde, lawyer Claude Langham exudes a confidence in court that carries over to his assuredness at home, where he maintains the role of snarky aggressor. While this aggression may be interpreted as a sign of professional competence, his wife, Sonia (Ellen Burstyn), refers to his attitude as “contemptuous” and his demeanor “hateful” and “ice cold.”

In the courtroom, as Claude attempts to convince the jury of Kevin Woodford’s (David Warner) guilt, Sonia is put off by his unfeeling pragmatism. She also takes a fancy toward Kevin. Claude says she is always seeking allies, a practice that has apparently been developing for some time. There is thus an instant suggestion of long-gestating hatred, one that endures because of a refusal or inability to disband from one another. It is a paradoxical spitefulness, one countered by an obvious negligence: Why put forth such hostility if they genuinely don’t care?

When Sonia proceeds to brings Kevin back to her and Claude’s house and attempts to seduce him just seconds into the door, the antagonism has a familiar ring. Claude enters and sees them together, expecting sex and appearing disappointed when it isn’t transpiring. Claude talks to Kevin about adultery, his wife’s body, their leaving together, all in a form of emotional masochism. The whole arrangement is often discussed with a casual detachment, as if he really couldn’t be bothered. By his own admission, the two live in “a state of unacknowledged mutual exhaustion,” where the best they can hope for is to “achieve the minimum possible friction.”

Sonia says her husband resents independence and likens him to jailer, commenting at one point, “Clever of you to catch me at 17.” In a recurrent pattern throughout all of these films, Claude has become an authority, and the restrictive interiors mirror the bounds of their relationship and his presumed need for control. The bitterness of this marriage is stifling, further accentuated by the confined settings and the fact that many of the disputes play out in domestic arenas. When she shows up with Kevin, it’s a blatant affront and a certain sign of their animosity. To sympathetically invite him to lunch is one thing, but to bring him to their home is a provocative gesture of willful antagonism, one that attacks any semblance of stability in the family.

On the other hand, the relationship between Bogarde’s Herman and Andréa Ferréol’s Lydia in Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Despair initially appears to be conservatively romantic, with his poetic observations, their joyful banter, and their playful flirtations. But such jubilance is deceiving. Once he encounters Felix (Klaus Löwitsch), a stranger he takes to be his doppelgänger, Herman’s composure is shaken and he hatches an insurance scheme hinging on the faking of his own death. Compared to the prior four films, Despair seems to have a wider variety of open-air locations, an external sign of freedom and mobility that befits the picture’s narrative impetus, which generally has to do with Herman’s looking for a way out of his increasingly stolid marriage.

Lydia says Herman is “masterful,” a term repeated by her grandiloquent cousin, Ardalion (Volker Spengler). Even in the opening sequences, with their relative amiability, Herman sexually orders Lydia around the bedroom. While it remains possible this is all part of a role-playing act, it becomes more likely that his commands are a result of his mean-spirited nature, of which Lydia is its primary target. He chides her as if a child and derides her as a simpleton, patronizing her for her dotty demeanor, saying she is stupid but also acknowledging, “Intelligence would take the bloom off your carnality.” He says the condescending rapport is mutual, but the conduct is clearly limited. She likes trash and is scatterbrained and messy; he is the opposite, and prefers it that way. There is an odd comfort in the predictability of their antagonistic relationship; still, he expresses frustration with a marriage that becomes a progressively arbitrary nuisance.

As Herman’s mental state deteriorates, his behavior becomes more and more erratic: indifferent one minute, affectionate the next. His treatment of Lydia turns on a dime, and when he is briefly affirmative, following an arrogant explanation and plea for false cooperation, she naively falls for his scheme, all based on a lie she thoughtlessly accepts. Herman’s exasperation at Lydia’s dimwittedness also leaves him blind, or more likely apathetic, to the relationship between she and Ardalion.

In this unsettling, provocative quintet, Dirk Bogarde gives one incredibly soul-baring performance after another, all of them tapping into common notions of universal love, yet subverting that familiarity by having these concepts emerge from the most off-putting of individuals. Far from the average view of a romantic male lead, Bogarde’s roles here, be they a troublingly sympathetic Nazi or a captivatingly murderous psychopath, are all connected by the persistent premise of an inability to possess or maintain a desired relationship. Though he did other film and television work during this period, none of those performances would match the visceral and disturbing quality of his work in those five features, standing as Bogarde’s greatest legacy as a performer and artist.

One thought on “Death and Despair: Dirk Bogarde, Unlucky in Love”

Pingback: Daily | Cineaste, Kiarostami, Diaz - FANCY TEMPLE CELEBRITY