The first thing David Oyelowo says as he walks into the room, smiling, is “it’s Sunday, so we’re gonna have church.” At a roundtable discussion, he spoke about the film A United Kingdom, and why it was so important to him to bring the story of Seretse and Ruth Khama to the screen – the heir to the chieftaincy of the largest tribe in Botswana married a white English woman the same year South Africa instituted apartheid. Even though both governments tried to keep them apart, they stayed together – and eventually were instrumental in liberating Botswana from British rule.

On the inspiration for the film:

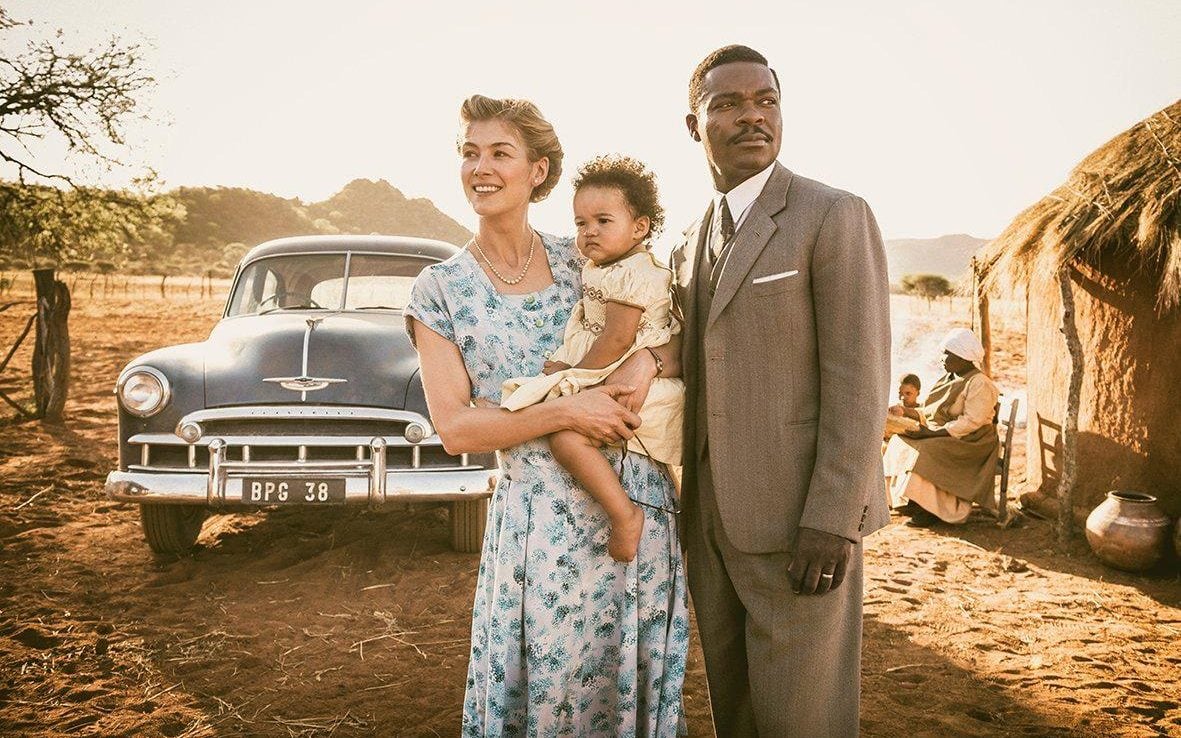

The very first time I happened upon it was when a producer I was working with about 7 years ago handed me a book called Colour Bar. It was about Ruth and Seretse, and it was the photograph of them on the cover of the book that just made me think, who are these people, why don’t I know anything about them? And then I read the book and just couldn’t believe how epic in scope their story was, and just very clearly perfect for a cinematic treatment.

On the effects of colonialism in Botswana:

The biggest effect of colonialism, I found, was the fact that very few people know this story. I have found, across Africa – and here in America, to be perfectly honest, and also in the UK, where I’m from – that there can be a selective history that is told that is very much incumbent upon dismissing bad behavior by Western regimes and accentuating heroic events that are to do with white Europe or white America. In Botswana, they know more about David Livingstone than they do about Seretse Khama. In fact, I turned up at the airport with my assistant, who is African-American, and the gentleman who came to pick us up from the airport saw Melanie, my assistant, and said, “Oh, are you going to be playing Ruth?” (laughs) Do you not know that she’s a few shades too dark to be playing Ruth?

But also, Botswana considers itself a post-racial nation, partly because of both Ruth and Seretse. They don’t recognize race, according to them. And being there, you really feel that, especially considering that Botswana shares a border with South Africa – race in South Africa is very, very different. Race is still very much at the forefront of everyone’s minds and dictates the way people behave. So knowledge about their own history was the starkest example of a postcolonial life that I witnessed.

On Ian Khama, Seretse and Ruth’s son:

Yeah, we did speak to the President – the current President is their son, Ian Khama – under the strangest of circumstances. We were shooting a scene that involved Rosamund [Pike, who plays Ruth] and Terry Pheto, Rosamund obviously playing his mother, Terry Pheto playing his aunt. And we heard this… (imitates helicopter blades) This helicopter suddenly landed on our set, and it was the President! And he stepped out of the helicopter, came and sat down next to me behind the monitor, and we were all a bit nervous – it’s the President, we’re playing his parents. Rosamund started doing this scene, and very soon after, he leaned towards me and said “I never thought I would see my parents again.” That was the most incredible seal of approval, in a sense.

On the triumph of love in today’s world:

A lot of people have said that the film is very timely. I think it is, but it’s also timeless. I don’t know that there’s ever a time where we feel like, yeah, we’ve got this love thing down. Oh, a united kingdom – yes, that’s what’s happening right now! That’s just not, unfortunately, the way we have been going. But I am a big believer in the power of love to heal, the power of love to obliterate those things that are different about us and to make us recognize that we are so much more alike than we are different, across racial lines, gender lines, age lines, religious lines. So yes, for me, the film is hopefully a tonic for people.

On faith:

You know, I think we’re very used to seeing lust on film being basically made to look like love, and I would argue the two things are quite different. In coming across this story, this felt like evidence of love, and not just love in a kind of Hollywood way. Sacrificial love, that kind of love whereby you are going to put yourself on the line, you are going to give to another person without the thought of getting back. And for me personally as a Christian, the greatest evidence of that in my life has been Jesus Christ, in terms of what he did on the cross for me, and I believe for the world. So I’m sure one of the reasons that really I was so inspired by these two is because again, what they did for each other, for Seretse’s country, was an act of sacrificial love.

On the topic of race in the UK:

In the UK, particularly, I think people were taken aback by the UK’s role in the story, and how few people knew about the story. There’s really abject shock as to Sir Winston Churchill’s role. [Churchill promised to reunite Seretse and Ruth once he won the election; when he did win, he exiled Seretse from Bechuanaland for life.] Understandably, probably quite rightly, he is a heroic figure, not only in the UK but across the world. But all politicians have checkered careers and moments where they were not necessarily their most heroic selves. This was definitely evidence of that in terms of Churchill.

But also, one of the reasons I really wanted to see this film come to fruition is that in the UK, unlike here in America, there are so few depictions – whether it’s on TV or film – of the part that black people, and people of color generally, have played in British history. As you well know, we love a period drama in the UK, but very rarely do you get to see anyone who looks like me. And so to be able to tell a historical story that very clearly has a black, African protagonist at its center – and the film is called A United Kingdom – is something that takes people aback. But there are so many stories like that in British history that involve people who are not white and male that we just haven’t seen yet.

On the reason behind producing this film:

Well, I’m a person of African descent who grew up in the UK and then spent a significant amount of time in Nigeria – I lived there from the ages of six to 13, seven formative years. I grew up around black men who were very self-possessed, who loved their families – my father, my uncles, my cousins. My dad is from a royal family – so, you know, I grew up with the kind of man with that bearing, that dignity. But they’re never talked about, or whenever you talk about an African leader, I’ve found it to be negative. People talk about leaders who are corrupt, who are hell-bent on being connected to the West in terms of filching from the country and the resources. And so to happen upon a story where, indisputably, here is a man who believes in love and is invested in his own community – I just wanted to see that, because it represents what I know to be true. I just have never seen it on film. And film is such a powerful medium. So many people’s estimation of what Africa is comes through film, or through media, or through TV, and by and large it’s negative, and it’s also often with black Africans on the periphery of the narrative. And so this was just an opportunity to show a different side of things.

On working with Amma Asante:

The reason I was very keen on it being Amma to direct this is because, like me, she’s of African descent – she’s of Ghanaian parentage, I’m of Nigerian parentage – but we were both born in the UK. And when it comes to films of this scope, of this scale, you almost never get to see that point of view – certainly not a female black British point of view. And her point of view was very important to me, because I knew her to be an unashamed romantic, and I wanted this film to be a love story more than a sort of political narrative. And I wanted someone who had a good perspective on the United Kingdom as well as an African nation.

So often, these stories are being told by a white male, and we’ve seen a lot of that perspective. That perspective is important, but we’ve just seen a lot of it, and so with time, what happens is it becomes the received perspective, the only perspective. And so therefore we go, oh, that’s what Africa is. But what you’re seeing with this… I mean, there’s a scene in this film where my sister and my aunt, in the film, confront Rosamund and say, “So what, you’re gonna turn up and be our queen? I don’t think so.” And that’s a black woman’s perspective on this story. And it wasn’t in there until Amma came along, because her perspective is important, and she wants to see that on film. So that is just one example of how perspective matters, and how her unique perspective is what created this particular film.

On advocating female directors:

It’s become a part of my life in a way that I didn’t anticipate. And I still find it troubling that I am anomalous. I find it troubling that I am unusual because about half of the directors I’ve worked with of late have been women. In a population where 51% are women, I’m the normal one! Everyone else is doing something rather odd, in my opinion. Yes, it’s something I’m proud of, and yes, it’s something I am vocal about, but I’m very troubled by the fact that it’s not improving. We’ve been talking about this for a while, and I think in 2006, of the 250 top-grossing movies in America, only nine percent of them were directed by women. In 2016, it was seven percent, so it’s now down by two percent.

And I’ve worked with enough brilliant female directors – Amma Asante of A United Kingdom, being one, Ava DuVernay from Selma being another, Mira Nair, who I just did Queen of Katwe with, another – that this notion that there aren’t enough of them, or that there’s a pipeline issue, is just not true. What’s happening is that the status quo is just being perpetuated. People are just not looking for them. They exist. The thing I always think about, is: today’s the Super Bowl, for instance. You want to have the best football team, you have scouts. You go across the country and you look for the best up-and-coming players in order to make sure your franchise is going to be the best it can be. Why there isn’t a concerted effort to find the best female up-and-coming directors, I just don’t understand. The amount of resources that studios have, that financiers have, and even just from people who say that they are socially conscious and allow this circumstance of a dearth of female directors to have the platform that they deserve. It doesn’t take a ton of money.

These people are doing great work. They’re posting on YouTube, they’re doing webisodes, they’re making films that are going to festivals. If you look at the highest percentage, representation-wise, of women behind the camera in the current Academy Award nominations, they’re women who directed short films. It’s a decent percentage, right about 30, maybe 40 percent of the films nominated. Go there! They are there, they are doing work that is worthy of an Oscar nomination. But that number is going to dwindle and disappear by the time it comes to Best Director – there’s no woman in the Best Director category this year, there was no woman last year. It just – it’s a disgrace, in my opinion. We can complain about the lack of women in Donald Trump’s cabinet, but he’s doing better than Hollywood right now, in terms of the percentage of women in the top fifteen positions in his cabinet. Two of them are women. That’s a higher percentage than female directors that are doing the top movies in Hollywood. So, the hypocrisy is also something that I find really damning. We’re just going to have to keep on talking about it until it changes.