When it comes to creating movies aimed at seasoned fans, most filmmakers are content to set their sights on remaking longtime existing entities with a firmly established canon. Whether they be superheroes, toys, or pop culture figures, as long as the mention of their characters’ names invokes nostalgia, their realization in a film franchise is a lucrative promise that studios are almost sure to bet on every summer or holiday season.

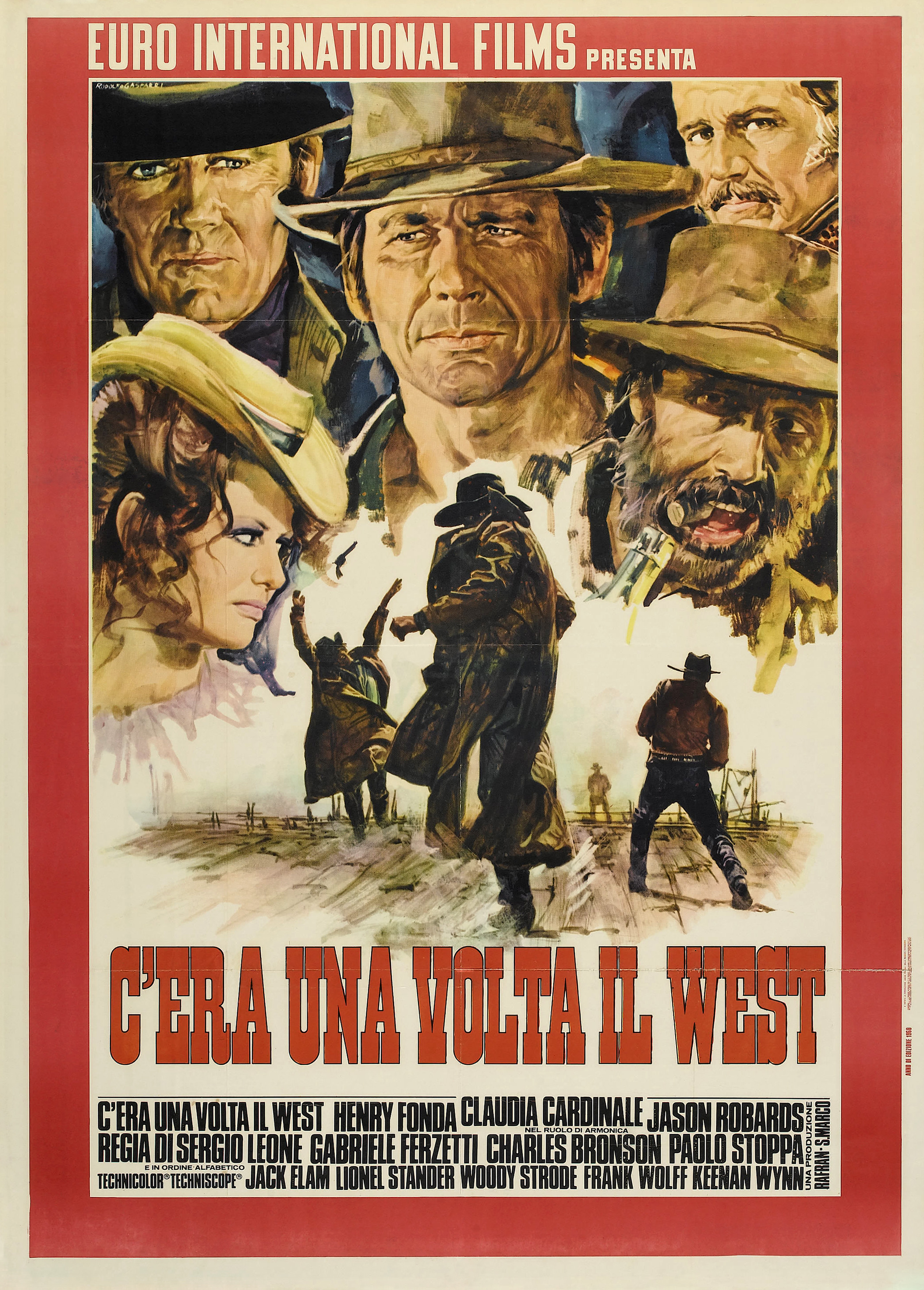

But rarely does a film come along with so much adoration for its canonical inspirations that it aims to be a tribute. Once Upon a Time in the West was not only one of the greatest Westerns, but it was a lyrical ode to the very idea of the cinematic West. Before Star Wars became a mere episode in its never-ending saga, it was the mother of all space operas. Raiders of the Lost Ark honored its globe-trotting escapist roots, as Roger Ebert wrote that it celebrates “the stories we spent our adolescence searching for in the pulp adventure magazines.”

Though it might seem like an unlikely candidate for a genre-embodying film, you could say the same about Pacific Rim. It is, as Hideo Kojima put it, a love letter to Japan’s literal celluloid giants, a film that isn’t content to merely visualize canon but looks to reclaim a childhood awe by forging new ground.

I hope you would accept this inspirational love letter that had traveled across the Pacific, written by Director Guillermo del Toro.

— HIDEO_KOJIMA (@HIDEO_KOJIMA_EN) July 5, 2013

Easy Comparisons

Though Pacific Rim has received a lot of praise overall, there have been more than a few criticisms dismissing the film as another loud movie featuring giant toys (which it is, though it’s also much more). The obvious dig is to compare it to Michael Bay’s Transformers movies, with their shared subject of monstrous-sized mechas. But that similarity is as far as it goes, as they both couldn’t be more different in tone and style.

Michael Bay’s version of these alien robots focused on sheen and extravagance, highlighting outlandish designs that strayed far from their archetypal origins. Giving Optimus Prime a moving mouth may have been Bay’s greatest mistake, providing just one of many ways of distancing this admirable father figure to a generation of kids, into a shiny albeit ungainly weaponized machine.

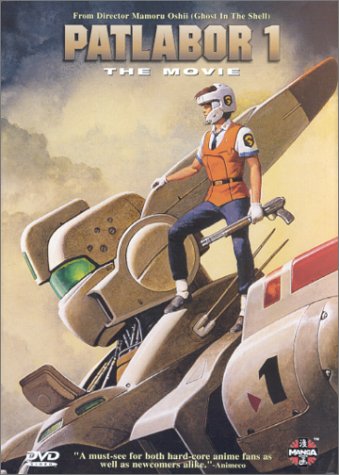

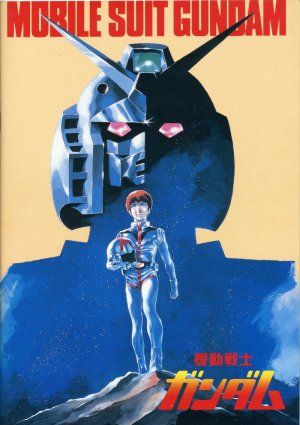

Guillermo del Toro’s “jaegers” (through Industrial Light and Magic) in contrast, are modern yet somewhat classical (in the mold of Yutaka Izubuchi’s Patlabor or Yohsiyuki Tomino’s Gundam designs), showcasing flat-plated surfaces with all the details in between. They appear more humanoid than machine, supplying a suprising grace and providing a smaller divide for the audience to bridge.

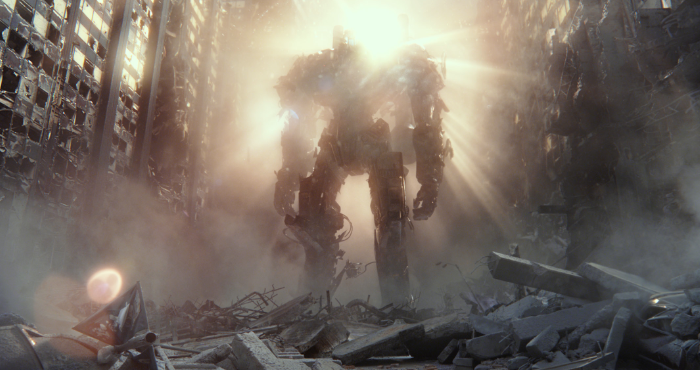

Michael Bay is capable of some amazing sights and perspectives, but his reliance on slow motion and “shaky cams” belies his weaknesses as a director. His shot composition can be all over the place, making little juxtapositional sense when the action starts. Del Toro sets a much higher bar, with masterful pacing, build-up and release. The slow motion of his mechas communicates their scale and heft, and though his action sequences take place in the dark, they’re still nowhere near as murky as confusing as Bay’s battles between Autobots and Decepticons. His “money shots” of jaegers and kaijus are easy to see, and at every point in the story we know where everyone is and what’s at stake.

Even in terms of characterization, the contrast is staggering. Michael Bay provides his supposedly intelligent extraterrestrials with misogynistic and militaristic qualities that betray his self-aggrandizing sentiments rather than convey the adventurous spirit their source was known for. Del Toro’s robots lack consciousness, but their human operators are afforded more dignity and respect, and by extension so is the audience. More on that later.

Another Piece of Disaster Porn?

As both The Guardian and The Economist have shown, Pacific Rim is sometimes cited as an example of disaster porn, where the presence of mass casualties supposedly reflects a desire to portray entertaining carnage for uncaring audiences. But mass destruction has been a staple of escapism for decades, and the ability to visualize our dreams and nightmares is one of cinema’s wonders. Ever-improving special effects continue to blur the genuine from the phony and add to our amazement or horror. But it’s not merely what is shown that determines our reactions, but how. In film, context matters more than content.

This is again easily demonstrated by comparing the war machines of Michael Bay and Guillermo Del Toro. Bay’s Transformers evokes a more warmongering outlook, with robots highlighting their fetishistic arsenals hand-in-hand with the U.S. military more than ready to launch a strike. In Pacific Rim, in contrast, Del Toro’s jaegers are called upon to protect and defend. Though their capabilities for destruction are obvious, the tactics employed by their British commander (Idris Elba’s Stacker Pentecost) focuses on minimizing casualties. You’ll see no call for an air strike, no bombing runs full of explosions, no people or robots holding guns pointed at targets. Sure, there’s the Australian Striker baring chest missiles, but the gesture connotes potency much more than it does aggression.

These jaegers employ defensive manoeuvres away from a major populace, and when they find themselves battling in the middle of a city it’s as a last resort, after calling for city-wide evacuations. Mass destruction does occur in Del Toro’s vision, but it isn’t voyeuristic for glossing over human loss.

Pacific Rim is also a martial arts film, with its giant protagonists pulling off poses and its pilots highly proficient in bōjutsu. And like most martial arts films where plot mainly exists as something on which to hang physical poetry, the aim of its cinematic combat is not to champion violence but to inspire awe at an entity’s abilities rather than the scope of suffering. Such conflicts are compelling because they are useful in suggesting a kind of oppositional purity. Good vs evil. Jaeger vs Kaiju. Mano-a-mano.

Another Big Brainless American Movie

The Wall Street Journal’s Jeff Yang came to this conclusion, deducing (at the time) Pacific Rim‘s lack of resonance in Japan due to its status as “a quintessentially American movie: A big, boisterous brawl between forces of cataclysmic destruction, best watched with brain on pause.” This of course was arrived at despite praises sung from Japanese pop culture icons Hideo Kojima, Go Nagai and Yoshiyuki Sadamoto cited in this piece among others.

But let us consider its American traits, if any. It is distributed by Warner Bros. and produced by Legendary Pictures. Its protagonist is American. But beyond that, it’s hard to see how else the Stars and Stripes shine through. The film features roles for China, Russia, Australia, Great Britain, Hong Kong and Japan. I don’t even think the United States is mentioned even once. Heck, even the Philippines (specifically Manila) got a shout-out. Though the film’s lead is American, he is played by a Brit. And while we’re keeping score, a Brit and an American plays the Aussies, and two Canadians play Russians. It’s enough to make you wonder what Del Toro’s casting director was smoking.

Near the end, none of the jaegers are left. The battles occur mostly in Asia. Maybe it’s “a quintessentially American movie” because most of the cast is white and English is the primary language?

Going back to that Manila shout out, I’m sure it wasn’t accidental. Before American cartoons reached our shores in the 80s, Super Robot Anime ruled our kids’ airwaves. They became so potent that Ferdinand Marcos banned several of them (most notably Voltes V) because of their underlying subtext about rebelling against a tyrannical aristocracy (I remember my relatives telling me to turn the TV off when they came on). After Marcos was deposed, these cartoons were the some of the first programs to be rebroadcast.

These mecha anime inspire deep emotions among Filipinos who grew up in the era, and many of us know their Japanese lyrics as much as we do our own national anthem. Some of their themes often appear on our karaoke standards. And though many of us may not know the literal meaning of their lyrics, the sentimentality of these ballads fits perfectly within Filipino musical sensibilities (Chichi wo Motomete can move any of us to tears).

So I beg to differ when Jeff Yang suggests that only “Western” kids might appreciate Pacific Rim, when as of this writing international audiences have embraced the movie with significantly more enthusiasm than their U.S. counterparts. Del Toro has clearly hit a nerve that has resonated across cultures, drawing from source material that is anything but American.

Needs Much More Than One Strong Woman

The only thing more egregious than Pacific Rim’s abundance of bad accents is its lack of women. But before I dive into that, let’s cite the positives.

I found Rinko Kikuchi’s Mako Mori to be the film’s most compelling character, and perhaps in some ways the strongest. Many have argued that she is a disgrace by being the weakest. She cries, fails to pilot a jaeger at a critical juncture, seems to eye her co-pilot romantically, and gets rescued near the end. All compelling points.

But we mustn’t overlook that she is given the film’s richest character arc through her portrayal in childhood by Mana Ashida. In the movie’s most powerful sequence, Del Toro reveals Mako’s trauma of parental loss and a terrifying confrontation of her worst fears. It is Mako who is most willing to overcome her personal horrors (even Raleigh shows reluctance when called to return to service). Though she requires constant guidance, is this due to weakness or inexperience (there is a difference)? Her early interests in Raleigh can be interpreted as physical attraction, but it could also be based on shared sufferings. There are many ways to view her, but conventions might push us to view her less kindly.

In a scene of one of Gypsy Danger’s most dire straits, it is Mako who refuses to surrender. Though she is “rescued” towards the end, she helps to rescue Raleigh, too. And though there are indications she might be romantically interested in Raleigh, Del Toro never allows them to act on such feelings. In the end, Mako is treated as Raleigh’s equal.

The only other female character, Lt. A. Kaidanovsky, is the brains of the Russian pair who pilot Cherno Alpha. But she doesn’t last long enough, as there doesn’t seem to be any other female in sight (aside from the lady who surrenders Newt to the kaiju). This is a massive and unjustifiable Bechdel failure. World War 2 churned out thousands of women who volunteered to help in the war effort, and not one can be spotted helping the jaeger resistance.

I can understand the criticism that there aren’t enough female characters, though I don’t believe it was done on purpose. Most pop culture of this sort has long been aimed at boys, but I know many women who rave about Pacific Rim as much as their male counterparts. I for one am looking forward to seeing it with my daughter when the time is right. But there is no excuse for the lack of female characters, and Del Toro would do well to take heed.

Fanboys want it for themselves

One final thing I’ve noticed is that different types of otaku fandom have claimed that Pacific Rim has appropriated their obsessions unfairly. The loudest noise comes from Evangelion devotees to the point that it has inspired a side-by-side trailer comparison.

But what does this prove? I’ve heard other anime fans tell me how much the movie reminded them of Attack on Titan, Tōshō Daimos, Mazinger Z, and a slew of other sources. With enough effort, one could easily make the same kind of trailer. If Evangelion‘s character designer can praise the film as “a huge, satisfying feast with the best prime cuts from Japanese tokusatsu (special-effects) and anime works,” isn’t that enough? The references are indirect, but the love is clear.

But what of complaints about how Guillermo missing the point about kaijus according to J.F. Sargent? Where is the metaphorical politicization that lives up to the spirit of the original Godzilla, where America must be held accountable for its foreign injustices? Even Jeff Yang points out how the kaiju films were originally made for adults and not for children, and he’s right. But though they’ve got their historical facts straight, it’s clear that it’s not Del Toro who is missing the point.

Was Del Toro trying to deliver a political statement or provoke some serious discussion of the global state of play? His aim is clear, to return to a spirit of childhood adventure which he first encountered in super robot and giant monster shows of the past. Was it a travesty when Steven Spielberg did not focus on the horrors of Nazi Germany in Raiders of the Lost Ark? There’s a proper film for every subject, and criticizing Pacific Rim for something it never tried to be, is misplaced and unproductive. Besides, the lack of an overbearing political timeliness in this blockbuster that simply aims to thrill, is actually kind of refreshing!

In the end, Pacific Rim brought back the giant robots and monstrous kaiju that helped enlarge my imaginations as a child long before Steven Spielberg and George Lucas entered my life. It seems apt that Del Toro follows in their footsteps, as Ebert once said best, “celebrating the stories we spent our adolescence looking for.”

One thought on “A Defense of ‘Pacific Rim’ Along with Other Reflections”

I enjoyed reading that but I disagree that we don’t see any females helping the resistance: I’m pretty certain there are several visible in the shatterdome floor and in the control room. However it would have been good to see more prominent females in the film.